On the Front lines of Indigenous Activism

Jasilyn Charger Channels Anger Into the Fight for Survival

When I was 18, I was really done with the rez, and so I moved away. A couple of my friends died from suicide while I was gone. And a couple more got murdered. When I came back, it was very traumatic. So many of our people we know end up trying to kill themselves. You just feel so alone. Like, nobody’s really going to help. No one’s going to help me protect my family, so what do I do? And it turns into depression. They start hurting themselves through drugs and alcohol, and they start giving up.

My friends, we were angry. What the hell is going on? What is our tribal government going to do? What is our school system going to do? What do we do? That’s what really kind of drove us. My nephew, Joseph White Eyes, he’s only a year older, was a youth organizer here at the teen center. He really educated me—pushing myself away from the negativity: the drugs, the alcohol, the partying. Showing me nonviolent direct-action books, pictures of places he’d been, people he’d met, and sharing his stories with me. He told me, “If there’s something you don’t like on the rez, you can change it.” He brought it to my attention that you have rights, you have a voice. That there are things you need to know that people aren’t automatically going to tell you, because they benefit from you not knowing. He started with protesting the taking of the buffalo, and that fight projected him to the Keystone XL (KXL) fight. I was, like, Wow. I want to be able to live my life this way.

So, I got involved in a local youth movement here—the One Mind Youth Movement. And they picked me and my friend to send to Washington, DC, for the Our Generation, Our Choice march. This was our first time on a plane, our first time going to Washington, DC, my first rally. I knew it was going to be something extraordinary, but never expected to feel the way I did. In that moment of being on the stage, you have all these people in front of you—thousands of people. At first, I wasn’t a very good speaker. I was just, like, crying and trying to get the words out. I knew that would happen, and so I wrote a poem. And that worked, and they loved my poetry. It was so awesome: We occupied two four-ways early in the morning when everybody’s trying to get to work. It just made me feel like I have a voice now. Like, I can make change through my actions. We felt empowered.

When I came back, I saw David Bald Eagle, one of the chiefs of our reservation who had taken me in when I didn’t really have anywhere to go. I told him I was so embarrassed that I started crying. He was drinking his coffee, and he just put his coffee down, like, “Sit down. I need to talk to you.” And he scolded me. I was like, I thought you’d be proud of me, or happy. But he was, like, “You told me that when you were crying, you couldn’t speak because you were scared.” He told me, “Whenever you speak in front of people and say you’re from this reservation, you’re speaking on behalf of everybody here. What you say, and what you do, reflects upon all of us. You have to be strong, to speak with conviction and passion. You can’t be scared. Because it’s not about you. Your voice comes from everybody you have ever known and loved, and all the painful things that they’ve gone through. You’re speaking for them.” Once he said that, I just wiped my tears, like, Yeah. I understand. And ever since, I’ve always tried to speak from my heart and take all the things that I’ve learned, and know, and experienced from the lives around me.

We started lobbying our tribal government to get more of the things we wanted done. We started telling more youth what was going on. Because a lot of them didn’t really know, and they’re like, “Whoa. Something needs to be done.” Exactly. When you give them the information, they inspire themselves. No one’s too young to be a leader. No one’s too young to start fighting for themselves.

Two months after we defeated KXL, we got a call-out from Standing Rock over the radio, a call-out to Indians across Indian Country. Like, “Hey, we’re having a No DAPL meeting about this pipeline going through our reservation. Come and show your support and share your stories and your wisdom.” Our mentor was like, “Who else wants to go?” We took a whole van full and went up there. They were really surprised, like, “Wow, we put a call out and we expected a lot of men to come. A lot of chiefs. And the youth showed up.” They didn’t really expect youth to care. Like, “Oh, video games and Facebook and Snapchat . . .” But we were doing this for all of our friends and family who can’t fight for themselves. To show them that no matter how much pain you go through, no matter what your situation, no matter how hopeless you feel, you keep on fighting.

We made people listen. Even our elderly. We made them stop fighting each other, and start fighting for each other.We do have those people who come and tell us, “You’re not supposed to do this.” It’s just not how it’s done in our culture. One of the examples of that is when we ran to Washington, DC, to bring attention to Standing Rock. We got a lot of backlash from the male figures of our community—the warriors, the headsmen, and a lot of the elderly. Because they felt that we were out of place. They were saying, “We wouldn’t send our women and children to war to meet with head officials to negotiate on our behalf. That’s not the women’s and children’s places.” And we were just, like, Well, if you wanted to do your role, you should have been the one to offer up to run for us. If you want to say that, then do something about it. Nobody was really camping before we started running—just, like, 50 people. And when we came back, there were thousands of people camping everywhere. I’ve never seen that many people camping together. We opened up eyes. We made people listen. Even our elderly. We made them stop fighting each other, and start fighting for each other. Our tribal people came because we challenged them, like, Hey, we’re running across the country. What are you going to do for this? What are you going to sacrifice?

I try to make my ancestors proud and my family proud. Because I want my elderly to leave this world knowing that the future of our people rests in good hands. And whenever they see us fighting on the front lines, and even getting hurt and getting beaten, we’re still persevering. Because our ancestors went through so much to just exist, just to have rights. Just to practice their own culture. They survived through hell and back. They marched across thousands of miles just to be placed on this reservation. Families were broken. People were lost. And I can’t live with myself without knowing I made the exact same commitment.

Native American children, we inherit so much stress, so much pain. And when we grew up, it’s like, Why are my people like this? We don’t like it. We’re not satisfied. So, I’m speaking up for what I feel, and I’m trying to do what’s right by my people. A lot of people look at me as a youth leader, but I feel like I’m more of a conduit of energy and information. No one’s too young to start fighting for themselves.

__________________________________

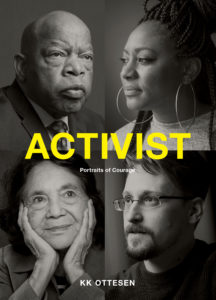

Interview by KK Ottesen. Excerpt from Activist: Portraits of Courage by KK Ottesen, published by Chronicle Books © 2019. Used with the permission of Chronicle Books.