On the Foods We Bring From Deepest Childhood Into Grown-Up Life

Lily King on Baking Elephant Ears

I didn’t bake with my mother. She was a good cook and made all kinds of yummy desserts—lemon meringue pies, bittersweet chocolate mousse, paper-thin sugar cookies, a bûche de Noël every Christmas—but I was never her helper in the kitchen. I knew to stay away. One of my earliest memories is of her whacking my hand with a wooden spoon when I’d tried to stick a finger into the bowl.

The first thing I learned to bake was chocolate chip cookies, something my mother never made. Most likely, it was my best friend, Becky, who showed me the recipe, which was in a spiral-bound, locally published book called Essex County Cooks. My mother and her contemporaries had all contributed recipes, and every house I knew seemed to have both volumes, one green and one red, though my mother had long moved on to Julia Child. The cookie recipe was in the green book.

The story was that a few years earlier some kids who lived down the hill from me and Becky had meant to make the standard Toll House recipe from the back of the Nestlé chocolate chip bag but either accidentally or deliberately messed it up. They used less flour and more vanilla. They added a tiny ¼ teaspoon of water. They melted the butter instead of waiting for it to become room temperature, and they cooked the cookies at a higher heat—425—for a mere 4 to 5 minutes. What came out was a tray of larger, thinner cookies that had to be removed with a surgeon’s precision and cooled for a few minutes before you could put them in your mouth where they burst into a buttery, salty, chocolaty swirl of perfection. They transcended debates of crispy or chewy. They were both at the same time. They were manna.

The kids called them Elephant Ears, and children in my hometown are probably making batches of them still. Soon our copy of the green cookbook fell open to that page, which grew translucent from smears of spilled melted butter, and crunchy from the grains of white and brown sugar that got stuck in the grease.

Most weekends and all summer, Becky and I made batches of Elephant Ears. We were in third grade, fourth grade, fifth grade. We’d be in my kitchen on Proctor Street or her kitchen on Beach Street. Someone would be stirring and someone would be calling WRKO to ask them to play “Rock Me Gently,” our favorite song ever.

Once, we wrote our own song made up of all the swear words we knew: “Fuck, shit, dammit all/We want to ditch it all/So we won’t become a bitch’s ass.” There were more verses, but I will spare you. We wrote out the whole song twice, a copy for each of us. We can still sing every word on command. (Becky and I fell out of touch for twenty years then ended up in Maine, with no planning or communication, three miles apart, and took up our friendship right where it left off.)

Fifth-grade summer we both got boyfriends who were best friends, and they gave us matching engagement rings from Foster’s Gifts downtown. We made cookies and met them on the rocks at the end of the beach. Halfway through that summer, I left town with my mother. She’d filed for divorce, and I couldn’t tell anyone we were leaving, not even Becky. When we came back before school started again, my mom and I moved into an apartment near the gift shop. I called up Becky, and she rode her bike down and said it was cool. She said all the lights on either side of the mirror in the bathroom were like the dressing room of a movie star.

We made cookies there and not at my old house where my father was living with his girlfriend and her kids. That kitchen was hers now, and she made brownies. I didn’t feel comfortable rummaging through the cabinets for an old package of chips. And she’d moved the table where we always mixed up the batter into another room. There were armchairs now, in the kitchen, and that was where she and my father did a lot of their drinking and their fighting. They liked an audience for all that they said and did to each other. I didn’t invite friends over when I went there on weekends.

This recipe, the memory of these cookies, is one of the few things that made it out with me.

I left the country as soon as I finished college. I found a job in Paris cooking for three kids whose parents both worked. They walked home from school every day for lunch. I made them a snack when they returned in the afternoon, helped them with their homework, and made them dinner. Within days, I was on a hunt for baking soda. It wasn’t in my dictionary, the Internet hadn’t been invented yet, and the grocer had no idea what I was talking about. I finally found it, bicarbonate de soude, at a pharmacy. A few years later, when I lived in Spain, I was able to find bicarbonate sodico faster. I made Elephant Ears in Vermont, New York, California, and back in Massachusetts. I made them for my boss at the bookstore in California and my coworkers at the restaurant in Vermont, and our guests when I worked at an inn on an island in Penobscot Bay.

I began baking the cookies with my children as soon as they could sit cross-legged on the wooden island in our kitchen in Yarmouth, Maine. There were negotiations: who would crank the sifter first, who would crack the egg, and who would stir it in. When the brown sugar came out, each girl could have just a “smoodge,” our word for a small pinch straight from the box. These cookies went to school for bake sales and birthdays, to neighbors for celebrations and condolences, to Santa every December 24th. They weren’t called Elephant Ears or Toll House or even chocolate chip. They were just cookies. We rarely made any other kind.

A girl named Emily lived across the street, and for many years she came over on weekends and summer days to play with the girls. She was a few years older than they were, an only child, and she liked playing oldest sister to them.

The summer Emily turned eleven, my daughters were eight and six. I remember a rainy afternoon baking cookies with the three of them. I had to go to the bathroom, and while I was washing my hands and hearing their happy baking chatter from the kitchen, I realized that Emily was now the same age I was when my parents split and I started shuttling back and forth between the apartment and my old house, and my father started revealing this other side of himself with his new partner. I was seeing a therapist then for these memories, for the exposure to the drinking, the rage, the sexual language and behaviors most parents try to protect their children from.

I didn’t know that at the time, didn’t understand how abnormal it was, didn’t feel particularly young—I was the oldest of the four of us kids in my father’s new family. The therapist was trying to get me to see how aberrant it was and to connect with that younger self, to feel what she’d numbed herself against and to give that eleven-year-old girl the love and protection she needed. I thought it was a silly and futile exercise. But when I stood there in that bathroom washing my hands, I finally understood that I had been Emily’s age, this young girl who wore braids like I had and played dress-up and still rode the least scary ride at the carnival.

They were calling to me from the kitchen: Is it a half or a fourth of a teaspoon of water? But I was crying too hard to answer right away.

I didn’t bring much stuff with me from childhood into adulthood. My parents had several marriages each, moved in and out of houses, didn’t save our things. I don’t have many memories either, not normal, everyday memories. Whole years are blank. It’s like my mind wasn’t imprinting, the recorder was off. This recipe, the memory of these cookies, is one of the few things that made it out with me.

My kids are nineteen and twenty-one now. They came home, like all college students, in March of 2020 to finish out the year online. The cookies get made at night now. We turn on a show, and Eloise says, “I’m making cookies,” and we get our smoodges and soon the warm cookies are bending over our fingers, and then they are melting in our mouths, the butter, sugars, and chocolate all whorled together then washed down with cold milk.

__________________________________

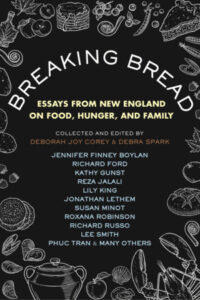

Excerpted from Breaking Bread: Essays from New England on Food, Hunger, and Family, edited by Deborah Joy Corey and Debra Spark (Beacon Press, 2022). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Lily King

Lily King’s novels include The Pleasing Hour, The English Teacher, and Father of the Rain. Her most recent, Euphoria, has won numerous awards and was named one of the ten best books of 2014 by the New York Times Book Review, is being translated into numerous languages, and will be a feature film.