On the Fear, Responsibility, and Boredom of Motherhood

Gabriela Wiener: Children Are Like Annoying Tourists

They look so small, so portable, that you want to pack them into a suitcase just to see if they’ll fit. These are impulses that over time a parent learns to repress. You have to monitor actions and reactions like a hawk to ensure you don’t cause the fledgling creature any permanent damage. That’s what this whole experiment is about. I used to think that when you become a mother you lose your stupidity all of a sudden; that some mechanism is mysteriously set in motion, and the autopilot on a trip to maturity gets automatically switched on. There is no such thing. I’ve taken many an honest look at myself in the mirror of motherhood. Sometimes you like what you see, sometimes you don’t.

One day, sooner rather than later, you’ll be disarmed by your child’s ability to laugh, the unflappability with which they take on the challenge of being your child. And you’ll see that there was nothing much to worry about. The healthiest thing is not to allow your child to think for one minute that you’re better than you actually are. Your best gift will be to save your child this one disappointment, probably the first of their life, because there’ll be plenty more to come.

Of course, you shouldn’t make them believe that you’re worse than you are, either. That would be an even bigger mistake, and could cost you their weight in therapy.

Sooner or later they will realize you’re not postmodern, just an imbecile; that you’re not funny, just careless and irresponsible; that you’re not strict, just bitter; that you’re not free-spirited, just a slacker; and that you’re not their friend, just their mother. But that will be further down the line. In the meantime, enjoy:

“Mom.”

“What is it?”

“Come here.”

“What’s wrong?”

“I’ll tell you when you get here.”

“Okay, I’m here, what do you want?”

“Got you!!!!”

Last night we took her to a café. With this cold weather, you can’t be out in the parks. Also, let’s face it, parks are boring. Since the smoking ban was put in effect, cafés have become the favorite place for mothers and children: a smoke-free space where mothers can rest their chin in their hand while the nice waitresses entertain the children with that magic thing that fills glasses with bubbly liquid. It was supposed to be a wild night out for us parents. She was going to have a sleepover at her cool uncle’s house. But when it was time for mommy to take her to her cool uncle’s house, the girl started talking like Tarzan. “Me sleep with Mommy.” “Home mommy,” “mommy home.” And before I knew it, we were all back at home and in bed. Increasingly insomniac, increasingly lucid. As we count sheep, I swear I can hear Dr. Estivill and Dr. González bickering in the background about their respective, diametrically opposed methods for putting children to bed.

“I’m not going anywhere, I’m right next door. See? There’s nothing in your closet.”

“Mom, I want to be with Mom. Mom, Mom, Mom. You’re so pretty, so intelligent. Mom, cuddle me to sleep.” She says it all with an irresistible smile, dewy eyes, and outstretched arms, and you have no choice but to get under the covers with her and give her everything she’s asking for, which is simultaneously not much and all you have, all you are, and all you will be. “Night, Mom.”

“Mom, I want to be with Mom. Mom, Mom, Mom. You’re so pretty, so intelligent. Mom, cuddle me to sleep.”

I made a pact with her: I would read her a story, then I would leave and she would read the next one by herself. She agreed to it. I couldn’t believe it. She found the experiment interesting. I would give her a little kiss and disappear. It was two weeks of heaven. But by the third week she hadn’t just annulled our pact, she’d regressed. I was back to reading her three stories, half of them in Catalan, by the way, while she corrected my absurd pronunciation. Then she decided I wasn’t going anywhere, not after three stories, not after song number eight, not now, not ever. Every night I curled up in a fetal position, my back breaking on the edge of her cute little Ikea bed.

I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not, I sleep, I sleep not . . . I pluck the petals off my dreams.

Basically, I believe that youth is a drug. Children are always in a state of altered consciousness. Which is to be expected, since they’ve been in this world for so little time. They’re like annoying tourists: excited about everything and leaving their plastic cups everywhere. Bedtime doesn’t even register with them. Today I read her the story of The Princess and the Pea. I had to read it five times because every time we reached the end she started crying if I didn’t start over. The fifth time I read it I was interrupted by my own heavy breathing and snores. If I started to nod off I’d hear a distant “Mommmmm,” a voice that came from far-off lands, and I dragged myself up to the surface, trying to climb out of that bottomless pit of sleep. I had no idea what I was reading, but it was my voice, of course it had to be my voice, and the next thing I know I’m wide awake and telling Lena about the King of Spain’s brother-in-law’s embezzlement conviction. That’s when I knew it was over. Increasingly insomniac, increasingly lucid.

Today I tried to explain to my daughter what “dead time” is: “There are moments when we do absolutely nothing, and life is full of those, my love.” She replied, “Who killed it?” I was going to say that what matters is not who killed it but how it was killed—but by then she’d already switched on the TV.

*

“Can’t you see I look ridiculous?” she exclaims, her eyes burning with indignation, as if she weren’t three feet tall. She knows nothing about life, and despite this, or maybe because of it, I can only take her seriously. Defeated, I remove the scarf from her fragile little neck before we head out to school.

When Dad (not just any dad: he does his equal share of housework and tends to take on the most thankless tasks) goes away, Mom (not just any mom, but me) is concerned about one thing only: how to fill the canvas of the 24 hours she will spend alone with her daughter.

The solution always tends to be the same: call a friend, reel them in under the pretense of grabbing a beer, and then end up in a play park next to the swings. It’s a good strategy to get away from other parents who are as obnoxious as you are.

But today, as is increasingly the case, I can’t trick anyone into coming. That’s why, as I head out of work to pick her up, I mentally prepare myself for the impending—fear? responsibility? boredom?

I wait for her at the gate and there she is, beautiful, her eyes burning with excitement when she sees me. She hands me a chorizo. That’s right, a damn chorizo she’s made herself on her trip to a farm. “In one minute and a half there will be a downpour,” she declares very seriously. But when we walk in search of our afternoon snack, the sky clears and I give in to the joy of having her all to myself.

__________________________________

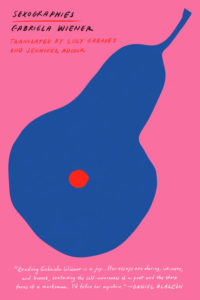

From Sexographies. Used with permission of Restless Books. Copyright © 2018 by Gabriela Wiener. Translated from Spanish by Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock.