On the Etymology and Reverberating Human History of the Color Green

Gillian Osborne Considers Color Theory and William Blake’s “The Ecchoing Green”

In his Theory of Colours, of green, Goethe writes: “The beholder has neither the wish nor the power to imagine a state beyond it.”

A hundred and fifty years later, of “the true Woman, the Mother,” Lukács, describing the difference between a monument and a gesture, writes: her longing stops at Earth.

Goethe: there is a placid acceptance in green. Lukács: that we extend to the feminine.

“Hence, for rooms to live in constantly, the green color is most generally selected,” one or the other continues. Hence, from Japan, riding my bike between train stations and the school where I worked, I imagined a green kitchen with peonies in California where I might be still. Hence, within that pale green kitchen, I nurtured starters, peeled, chopped, turned, sheltered from the Technicolor.

In Japan, a novice and a Granny Smith Apple are blue. In California, the plum trees bloomed around the same time. My kitchen window looked into a nutritive evergreen that might have been Vermont, which I remembered, except that the outlines were all otherwise: little live oak.

Hence, within another adopted landscape, I crimped a pie, became a mother, grew older. I learned gradually, within that context, a peony would be an impossible, thirsty, pink.

In English, geography is grafted into the etymology of green. The word comes from German (grün), and in nearly all Germanic languages, it carries similar connotations, green as the antithesis to deep winter: fresh, youthful, of grass, of ground, of fruit and vegetables, hopeful, healthy, though also, in this newness, untried or untreated. In England, many places were named for their greenery. Hence, above all, Greenwich. A wich being a settlement, one especially characterized by industry. And Thickly Settled, as signs say along New England by-roads. In upstate New York, everyone pronounced the w: Green-witch. Green, in that corner of the country, also being so especially bewitching as to seem almost wild alongside all that settlement. Within weeks, it over-runs everything in Massachusetts after epochs of death.

All this makes green a tonic color, both harrowing and nourishing. Blue: unadulterated yearning for the infinite. A sky. And yellow: what gets worshipped on Earth, sun and wealth. Green is other to these elementary desires. The idea in green is of the necessity of being with. We see these meanings of green in William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience, where green is the “other” color. The colors being not really colors at all: white and black; silver and gold.

Against these binaries, we might call it the middle color: color of melding, mixing; of democracy and striving; of the instability of life as it is actually lived.

“The Ecchoing Green” is also the third poem in Blake’s book. The first poem introduces poetry. A speaker cuts a “rural pipe” from a reed and pipes a cheerful song. The second poem introduces the pastoral. A shepherd guards his innocent sheep. There are no colors in these poems. There is music and there is relation: between the poet and his childish audience, between the shepherd and his animals.

“The Ecchoing Green” breaks with the immediacy of lyric expression—a poet, singing—and the generic history of the pastoral—shepherds singing to their sheep from the classical era to Blake’s late 18th-century—by extending these aesthetic relations into the unsteady dynamism of the social sphere. The ecchoing green is the village green, domesticated green. The poet pipes his songs, like Orpheus, directly into “valleys wild.”

The shepherd watches his flock in the “sweet lot” of pasturage. But the communal green is where people mix with one another, young and old, playing and slowly fading, ecchoing. Green, as it echoes on the green, is the color of human community: of history, migration, mingling, haunting. With green, the first real loomings of experience, which shade the remaining poems of Blake’s collection, emerge.

This transformation—from the innocuous to the ominous—then plays out across three stanzas, which, in turn, in their tripartite arrangement, reinforce the opening triptych of the first three poems. A poem of poetry. A poem of pastoral. A green poem, ecchoing. Innocence, Experience, some middling condition that is not quite one or the other, is both/and. White, Black; Silver, Gold—Green. Among other things, experience is the failure of humans—because of how age, race, class, gender, and what Blake might call unnatural religion mediate mutual perception—to reconcile in a shared middle.

Each stanza concludes with a refrain:

On the Ecchoing Green

On the Ecchoing Green

On the darkening Green.

In the first, the echo is purely innocent, an affirmation of joy, sunshine, bells, birds of song, and spring and spring: the healthful resounding din of children at play. In the second stanza, the echo is already a paler imprint of an earlier occasion of joy, a memory cut off from its original event. “Old John” and “the old folks” remember when they were that young.

Echoing the first poem of the collection and its celebration of lyric immediacy, the first stanza of this poem hums with the immediacy of play. And, just as the second poem is about the pastoral as a genre that reverberates with history, this second stanza is a reminder of the variable spaces and distances between articulation and any echo. How far a song must travel before it finds something against which to fling itself back.

In the final stanza, the sound of the echoing green is substituted for another sense: the darkening green, from which light, and so color, is sapped. Sight isn’t the opposite of sound, though. They’re merely non-commensurate. There’s a half-step in the movement from echo to dark that is dissonant, but gently so, drawing unlike and like into community with one another: immediacy and memory; pleasure and loss. White, Black; Silver, Gold—Green.

All this makes green a tonic color, both harrowing and nourishing.

This final stanza of Blake’s “The Ecchoing Green,” as it is with all middling ways, all third colors, is the most open to interpretation. It might simply be a description of the end of the day: boys and girls, come in from play. But the move from present activity to the abstraction of memory might also continue into the wrestling of present and abstraction that is allegory: in which something is this concrete this while also being that abstract that. A village green that is also the green of graveyards, or of Elysian Fields. The green of Mt. Auburn Cemetery—which was designed before, and so includes, the Civil War—is green like that. A place for the dead, designed for collaborative strolling among the dead and the living. One should be allowed to picnic there right now.

An external perspective runs through the allegory of Blake’s poem, further opening it to contexts beyond those any book might contain. In the penultimate line of each stanza, the one before the refrain, Blake injects a passive construction that insinuates an unseen seer into each scene:

While our sports shall be seen

On the Ecchoing Green.

In our youth time were seen

On the Ecchoing Green.

And sport no more seen

On the darkening Green.

The verb tenses slide from subjunctive, to past imperfect, to simple past, but the passivity of each remains consistent. This lurking, unnamed, looker is the first imposition of a god in Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and it should be spooky because it is also that middle way, that living green that echoes and darkens, an outside that is in everything, haunted humankind. Silver, Gold; Black, White—Green.

Turning from the human, though not fully, the final stanza of “The Ecchoing Green” also unfixes time from narrative linearity in its first line: “Till the little ones weary.” Is this “till” retrospective or prospective? Have the actions of the final stanza already happened? Or are we stranded, in the space between stanzas, until some yet to be disclosed requirement is met?

Of the “Allegorical, Symbolical, Mystical” uses of green, Goethe writes: “In this there is more of accident and caprice” and “the meaning of the sign must be first communicated to us before we know what it is to signify; what idea, for instance, is attached to the green color, which has been appropriated to hope?”

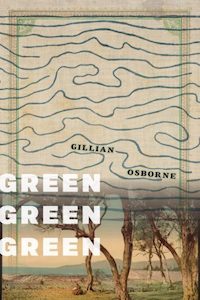

Green is an echoing color, a space of meeting and reverberation at the middle of the spectrum. So if Green Green Green is a book about a color, about when and how a color becomes material, there are many greens in it—a repetition of green that is also an articulation of difference each time it is voiced—a catalogue of green in which things are stripped of the fullness of context and yet vibrationally, referentially, living—the seasonal disorders of green across arguing geographies—the California winter, cloaked in wet—and the riot of midsummer along the eastern western rolling hills of New York—the entanglement of biography and biology—the sacrament of shared lives and dependencies—the fitting together of fungi and algae into lichen—the ribbing of blood in veins, sap in leaves—green green green, without punctuation, paratactic and aligned.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Green Green Green. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Nightboat Books. Copyright © 2021 by Gillian Osborne.

Gillian Osborne

Gillian Osborne is the author of Green Green Green, published in 2021 by Nightboat Books. Trained as a poet and scholar at UC-Berkeley, she was a co-organizer of the Conference on Ecopoetics in 2013, a fellow at the Harvard University Center for the Environment from 2015-2017, and is the co-editor of the anthology Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field. She teaches and designs curriculum for Poetry in America and the Bard College Institute for Writing & Thinking.