On the Endless Symbolism of the Best Summer Movie Ever Made: Jaws

And How It Owes Its Dark Soul to Moby-Dick

[This post contains spoilers for JAWS]

I watched Jaws this past Fourth of July, as I do every year, in view of its timelessness as well as its seasonality. Jaws, which is specifically set during Independence Day, also generally invented the “summer blockbuster,” a detail which makes its 1975 premiere on midsummer’s eve seem quite significant, in hindsight. Like the shark that arrives off the coast of Amity Island in the film’s famous opening scene, Jaws arrived unassumingly at the start of the season and caused a frenzy that would ripple out far past Labor Day. It became one of our greatest filmmaking touchstones: a marvelously intellectual monster movie, an arbiter of cinematic summer, a technical origin story for the boy-genius director who would become Steven Spielberg. It is also a touch prescient. It is one of those eerie films that, to me, feels a little sibylline, a little otherworldly. It seems to sit at the nexus of everything—the past, the future, high art, popular entertainment, mythology, history—as a film whose deliverance certainly revolutionized filmmaking and scared everyone from going in the ocean, but also stands as a vessel for the summoning of mankind for reflection and atonement.

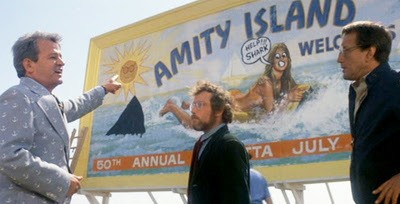

Not unrelatedly, another reason I like watching Jaws amid all the fireworks is because it localizes so many of the depressing actualities about America—the movie features a mayor who cares more about the local economy than the lives of his citizens, a medical examiner who covers up inconvenient means of death for gain, a scientist no one listens to, and in a new and relevant reflection, beaches being open when they shouldn’t be. But these aspects are not incidental to Jaws; the film is very much a pointed criticism of our particular American condition, one which places greater value on the perks of convenience and capitalism than on human lives. Neatly dovetailing all of this is Jaws’s constant stressing the insignificance of human civilization and the puniness of human existence in the face of nature. The name of the town is Amity Island, which is also the name of the land mass it totally subsumes; with this, and in other ways, Jaws represents humanity’s confusion between society and geology, buying into the fallacies of possession and property. I like the way Jaws does this—the shark both reveals the flimsy constructs of the human world, yet simultaneously presents an enormous construction of the human world: symbolism. In a way, the most penetrating and devastating thing the Amity residents have to deal with is not a literal shark, but the metaphorical implications brought by one.

Jaws is motivated towards everything else by its central revenge story.

Most simply, Jaws is about three men on a boat who hunt a gigantic, ravenous fish. In this way, and in many other, obvious ways, Jaws can easily be read as a modern adaptation of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a novel which, in the words of David Gilbert, features “so many symbols as to render symbols meaningless.” The meaningless of symbols, or really the curiosity about whether anything actually has meaning or means anything, are also all prevalent themes within Moby-Dick. In his essay on Melville’s novel, Gilbert goes on to quote the narrator Ishmael: “And some certain significance lurks in all things, else all things are little worth, and the round world itself but an empty cipher, except to sell by the cartload, as they do the hills about Boston, to fill up some morass in the Milky Way.” Like the white whale hunted for the length of the novel, the great white shark in Jaws is endless in what it might stand for and it also might stand for unknowability of what things stand for. Jaws might be an environmental parable, a fable about human greed, a document about the death of the small New England town and the New England fisherman, a horror film, and a satire or even condemnation about the potential inconvenience of facts. It stresses how inconvenient facts which concern something large and un-manipulatable like biology are ignored by political systems with much to gain by dismissing them.

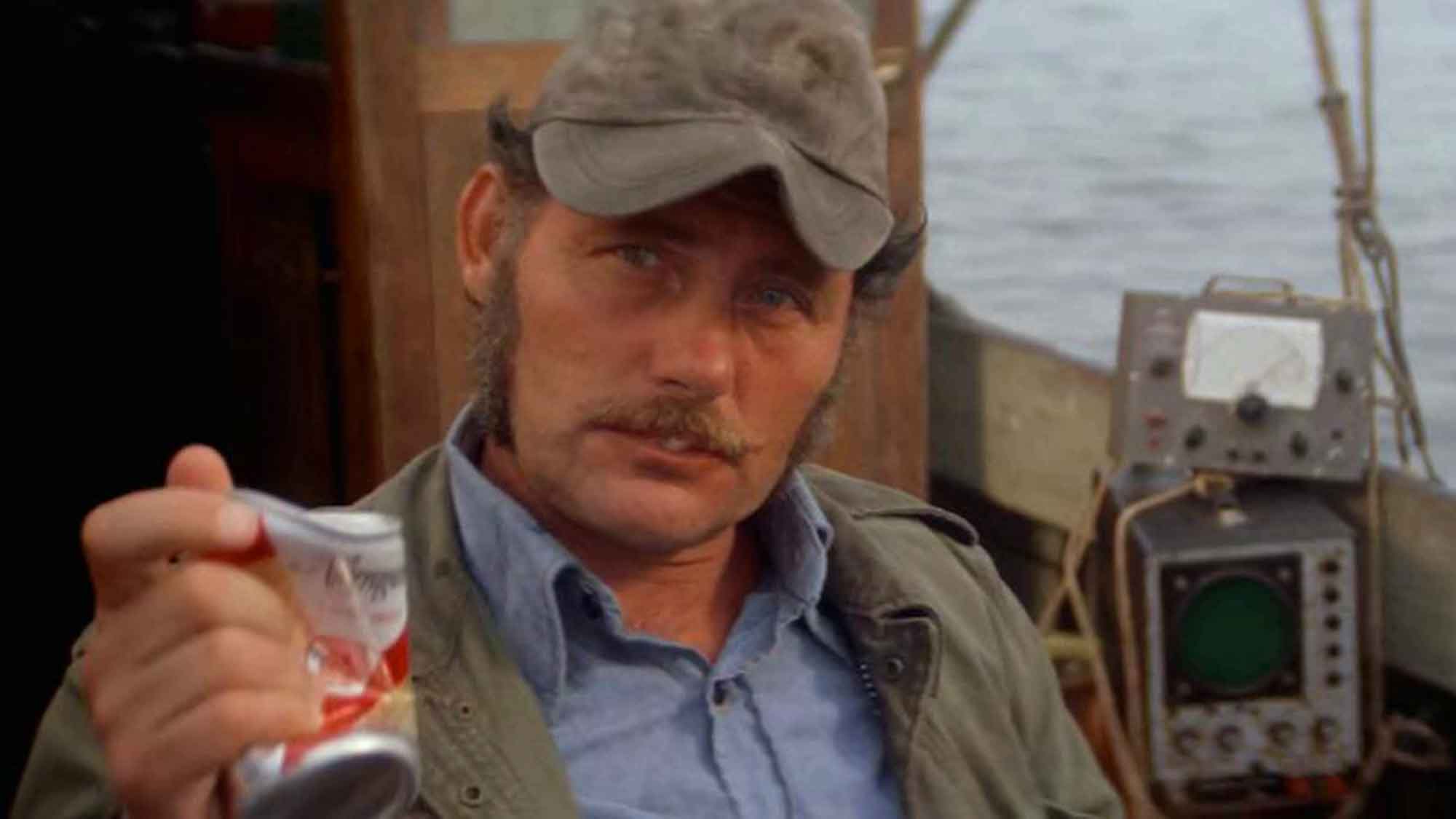

While Jaws initially presents the story from another main character’s perspective, like Moby-Dick, it is motivated towards everything else by its central revenge story: Captain Ahab hunts the sperm whale that bit off his leg; Quint (Robert Shaw), a grizzled Amity fisherman, longs to hunt the great white shark that has been terrorizing the island. This hunt is framed by the redemption narrative of Police Chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), who is swayed by the town’s mayor (Murray Hamilton) away from confirming that a killer shark has attacked a swimmer—an act of cowardice that costs many their lives.

No character actually puts into perspective the inconsequentialism of human hang-ups in the face of the natural world, and the simultaneous symbolic potential of absolutely everything, like Quint, whom Martin eventually forces Mayor Vaughn to hire, in order to trap and kill the shark after too many people have died in the water. Brody, Quint, and Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), a wiseacre oceanographer, board Quint’s creaky boat to go find, chase, and destroy the shark. For a while, their chafing dynamic allows Jaws’s political wisdom to seem temporarily backgrounded for the sake of interpersonal conflict. Hooper is a young, wealthy scientist who depends on gadgets in addition to know-how, Quint is an older, working-class sailor who relies on experience (and is contemptuous of Hooper), while Brody is a middle-aged, seasick city cop in galoshes and carrying his own holstered pistol; none of their methodologies align. But then, one night, they sit in the galley of the boat and, sparring lightly, start comparing the scars on their bodies.

Quint shows off his missing tooth, which was knocked out during a fight. He makes Hooper feel a lump on his head, which he got on one St. Patrick’s day in Boston. These two continue at this for a little while. Hooper’s scars are all marine (a moray eel bit through his wetsuit, he was scraped by a bull shark while he was taking aquatic samples, etc), while Quint’s are more varied. He demonstrates that he can’t extend his arm fully since losing the semi-finals of an arm-wrestling contest at a San Francisco bar, where he celebrated his “third wife’s demise,” and peels up his pants to show a thresher shark wound on his leg. Quint’s scars are the proof of a lifetime spent brawling, while Hooper’s are all aquatic and reflect his passion for his work.

Then Brody, who has been shy and silent so far, asks Quint about a scar on his arm. It’s the spot of a tattoo removal—a tattoo that had commemorated Quint’s service on the U.S.S. Indianapolis, the World War II ship that was on its way from delivering the Hiroshima atom bomb parts, when it was torpedoed and sank. “Eleven hundred men went into the water,” Quint recounts. “Didn’t see the first shark for about a half hour.” Here, he carries the film’s gravest scene—uttering a slow, haunting monologue about the week he spent floating in the Pacific Ocean in his life jacket, waiting either to be rescued, or eaten by a swarm of sharks. “Because the mission had been so secret,” he explains, “no distress signal had been sent.” He describes seeing, and hearing, his friends get attacked in the feeding frenzy around him, while waiting for his turn to die. But he is one of the few who makes it out alive. “Eleven hundred men went into the water,” he repeats, concluding the story, “three hundred and sixteen men come out. The sharks took the rest. June the 29th, 1945.” He adds, “I’ll never put on a life jacket again.”

Quint knows what it’s like to feel that his life is insignificant—forgotten by civilization, and left at the mercy of an unfeeling natural world. But his speech does more than provide the monster movie with tragic gravitas; it ushers in a spiritual dimension. When the shark comes to Amity (on June 28th, 1974) it is almost thirty years since Quint’s life was spared by the sharks while floating in the Philippine Sea. Rather like Moby-Dick’s Captain Ahab, who spent his life chasing the whale that had once bitten off his leg, Quint has squandered the life he was effectively gifted back by the sharks that day. Like Ahab, Quint should have died from his encounter, but he didn’t. Both men do not see this as the blessing that it is.

It is plausible that the massive, highly-intelligent, vaguely-supernatural-seeming shark is an angel of death, coming to claim Quint after his wasted and vengeful life, at the dawning of the anniversary of his survival.

Both men waste their lives, then, on petty things: (between the two of them) revenge and brawls and divorces and grandiose pursuits to destroy the creatures that haunt them. Ahab hates the whale. Quint hates sharks. When Brody hires him, Quint’s disinfecting full rows of shark teeth, likely from a fresh kill, to mount on his wall along with the rest of his enormous, creepy collection of shark jaws (which foreshadows, in a way, what will happen to him).

In light of Quint’s backstory, it is plausible that the massive, highly-intelligent, vaguely-supernatural-seeming shark is, much like Ahab’s White Whale, an angel of death, coming to claim Quint after his wasted and vengeful life, at the dawning of the anniversary of his survival. Or maybe, dovetailing with Moby-Dick’s themes of predestination, there is no free will in Jaws and a shark circles back to claim Quint, because this has always been his fate and he can never escape it.

On the boat, in the film’s third act, the conditions of Quint’s near-death in June of 1945 begin to recreate themselves—as the shark drags them further out to sea, beginning to dismantle their vessel, Quint destroys the radio while Brody tries to call to shore for help. He sees the orange life jackets hanging in the corner and refuses to put one on. When he does die, he is killed in the same manner as one of the friends he had mentioned in his story—bitten in half below the waist. And after the shark sinks his teeth into him, it hauls his body down into the depths, where it will rest forever.

Reading the shark as a kind of divine agent, and specifically a punisher, allows Jaws to become a film ruled by, of all things, the notion of salvation

Reading the shark as a kind of divine agent, and specifically a punisher, allows Jaws to become a film ruled by, of all things, the notion of salvation—which is a highly individualized concept. The fascinating argumentative logic of Jaws enforces that small human problems are inconsequential, but also that humans, small and unimportant though they may be, have individual roles which can bear great meaning. After all, the film’s shark problems technically begin in 1945, when a group of men mobilize to initiate the launch of a planet-destroying bomb—an act controlled by a small number of people, but with enormous consequences for earth. It tracks that the torpedoing of the Indianapolis and the tragic mauling of its sailors by nature itself, is positioned as a kind of punishment for their part in mankind’s hubristic effort to play God. Quint is marked by this event (literally, as the scar-comparison scene shows), and its implications will chase him. He realizes this, too. His destruction of the radio and refusal to put on a life-jacket suggest that he knows there is no point in trying to escape. Like Ahab, the maddened Quint doesn’t care what happens to the others on the ship.

But Moby-Dick is not only the story of the doomed captain caught in a cycle of his own destruction; it is also about the one left to tell the tale. If Quint is Ahab, than Brody is Moby-Dick‘s narrator Ishmael, the sole survivor of the voyage after the whale breaks apart their boat, and who is found floating in the water, clinging to the remains of the wreckage.

Jaws offers its Ishmael a chance of redemption in a way that is irrelevant to Moby-Dick; Ishmael is a bystander in the quest for the White Whale, but Brody must participate in the vanquishing of the great white shark. Amity Island’s microcosm of earthly problems helps communicate the profound effects simple choices can have; indeed, explaining why he uprooted his family to beachside New England, Martin Brody declares “in Amity, one man can make a difference.” Therefore, just as the shark is there to collect Quint, it is also there specifically to be vanquished by Brody—a man who had been very aware of the coastal presence of a man-eating shark but did not override pressure from a local, desperate politician to keep the beaches open. At this early point in the film, Brody has a chance to save many lives, and effectively passes this up. “I heard,” says Mrs. Kitner, the mother of a little boy who is (preventably) eaten by the shark during a crowded beach day, “that a girl got killed here last week, and you let people go swimming anyway.” He won’t make this mistake again, recognizing an opportunity for redemption, when he sees it. This is the ultimate difference between Brody and Quint and it does suggest that the universe of Jaws is indeed controlled by free will.

Going out on the boat, despite a longstanding fear of the ocean, Brody has the opportunity to undo his initial wrong. The end of the film involves a showdown between Brody and the creature on the wreckage of the vessel, the Orca (another name for a killer whale, which, like all the whales in this essay, is not actually a whale). At this point, Quint is dead, and Hooper (hiding in safety after his own brave confrontation with the shark) is irrelevant. Brody blows up the shark, shooting a rifle into a tank of compressed air that he has wedged inside the shark’s mouth—erupting a small mushroom cloud of guts and blood on the surface of the ocean. The explosion looks particularly atomic; as though it has embodied some connection to the U.S.S. Indianapolis’s mission, this whole time. The shark’s death signifies a symbolic completion of Brody and Quint’s debts, but it also emphasizes, briefly, hopefully, that a single individual has the power to repay the accumulated damage of many who came before.

These are universal themes, but Jaws, like Moby-Dick, is a story that is specifically American, and within that, about New England, the oldest region of the country. Indeed, the film commemorates the Fourth of July—the day which is credited as the very founding of America. The ending of Jaws offers a hopeful reading about the future of the country, whose legacy is otherwise presented as highly destructive, in everything from military campaigns to local capitalism. The arrival of the shark may cause “a panic… on the fourth of July,” as the mayor says, but the giant hoard of vacationers who swarm Amity Island during the Fourth of July weekend are another kind of plague: an overwhelming mass of individuals developing and overrunning the natural world for their own pleasure. The shark, which causes the crowds to recede, might be there to check humankind, to prevent the full takeover of nature by people. But it also might be there to check America, the country which leads the world in humankind’s insistence on the superiority of man over the natural world.

Or perhaps, relatedly, the shark is asserting nature’s ultimate control over the region; the swimmers taken by the shark (a teenage girl, a little boy, a dog, and two middle-aged men) are plausibly sacrifices, prices society has to pay if they insist on going in the water, at all—invading a habitat they have no biological need to occupy. Indeed, when we finally see the shark for the first time, it’s while the men are on the boat, and the three crewmembers agree that they have never seen a shark so enormous. Quint shoots three barrels of air into it, and the shark is strong enough to pull them back under. And the shark is incredibly intelligent—it has strategized how to isolate the boat in dangerous open water, and it methodically strips it down. “Smart fish,” Quint remarks, but this is an understatement, and he probably knows it. One of the film’s original taglines compared the shark to the Devil, but, like the White Whale, it also might very well be a God.

Olivia Rutigliano

Olivia Rutigliano is an Editor at Lit Hub and CrimeReads. Her other work appears in Vanity Fair, Vulture, Lapham's Quarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Public Books, The Baffler, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Politics/Letters, The Toast, Truly Adventurous, and elsewhere. She has a PhD from the departments of English/comparative literature and theatre at Columbia University, where she was the Marion E. Ponsford fellow. She hosts the podcasst "Culture Schlock" at Lit Hub Radio. She is on instagram at @oldebean, twitter at @oldrutigliano, and bluesky at @oliviarutigliano.bsky.social.