On the Diplomatic Mistranslation That Changed the Course of History

Anna Aslanyan Considers the Delicate Balances of Wartime Communication

On July 26, 1945, the Office of War Information in Washington issued the Potsdam Proclamation, an ultimatum demanding that Japan, still at war with the Allies, surrender. On learning of it the next morning, the Japanese foreign minister Shigenori Togo did not see it as a command to surrender unconditionally, and instead proposed negotiations with the Allies, urging the government to treat the matter “with the utmost circumspection, both domestically and internationally.” One of the cabinet members disagreed, proposing instead to reply that they regard the proclamation as absurd, but Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki supported Togo, and it was decided to publish the text in the press without comment. The papers, however, couldn’t help remarking on the ultimatum, which they considered a “Laughable Matter,” to quote one headline. Another compromise was found: the prime minister would read a statement making light of the proclamation without rejecting its terms. At the press conference, Suzuki said that the government did not think the document very important, adding, “We must mokusatsu it.”

The Japanese word literally translates as “kill with silence,” though Suzuki later told his son he had intended it to convey “no comment,” an expression for which Japanese has no direct equivalent. The Americans translated it as “ignore” and “treat with silent contempt.” On July 30, the New York Times front page announced, “Japan Officially Turns Down Allied Surrender Ultimatum.” The fate of Hiroshima was sealed.

Historians are quite right to point out that the tragedy wasn’t caused by translation difficulties alone. Yet debates around the translator’s role, as old as the profession itself, always revolve around the question of their agency. In our multilingual world the balance of history, unstable as it is at the best of times, hinges on different interpretations of words. Some translators believe themselves to be a mere conduit, ideally an invisible filter through which meaning flows; others argue that it’s far less straightforward: in the end, they use their own words, accents and inflections, and so they inevitably influence things. Can translators take liberties? Should they? The nature of the job, as we are about to see, means that interventions are hard to avoid.

In our multilingual world the balance of history, unstable as it is at the best of times, hinges on different interpretations of words.

When Donald Trump referred to certain states as “shithole countries” in 2018, translators the world over took the trouble to mitigate this definition. The most polite version, used in Taiwan, was “countries where birds don’t lay eggs”; Japan went for “countries that are dirty like toilets”; in Germany they said “garbage dump”. The same year, the international media interpreted the word used by Jair Bolsonaro during the Brazilian presidential campaign, limpeza, as “clean-up.” What did the candidate really mean? Did this translation underplay the predicament of his enemies, who might have actually been threatened with “cleansing”? However broad the spectrum of meanings hidden in the original message, a translator’s choice of words can have immense consequences. When the literal phrase “Death to America”—widely used in Iran since the 1979 revolution—is rendered as “Down with America,” the world begins to make a bit more sense.

My own work as a freelance translator and interpreter has never, to the best of my knowledge, tipped the scales of history. But it has given me ample food for thought, allowing me to see more vividly the figure of the translator surrounded by precarious events in which they cannot help intervening. It is this image that I would like to outline in these pages.

Human communication, even in one language, always comes with the proviso that we understand and are understood much less than we hope. Early in my interpreting career, a court case made this especially clear to me. The woman I was interpreting for sat there with her head buried in her hands throughout the hearing, which concerned the custody of her child. I didn’t realize at first, and she wouldn’t say when asked, how little the legal formulae (which I did my best to translate, showing off my recently learned legalese) meant to her, when all she wanted to know was whether she would be reunited with her son. When the judge got to “It would be my intention to allow this appeal” she still didn’t react to the good news. Afterwards, as her lawyer explained the judgment in plain English, I duly interpreted it, feeling the dead weight of dictionaries falling off my shoulders as she looked up and nodded. This time she understood it all.

*

Anyone who has ever tried translating anything will be especially interested in gaps between languages: gaps created by conceptual differences and cultural assumptions. It is in these often overlooked spaces that translators must make decisions, often relying solely on their own judgment. What else are you to do when you are the one holding all the cards? What informs this decision-making process is your belief in the translatability of human experience.

The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset opens his famous 1937 essay “The Misery and Splendour of Translation” with the claim that translation is a utopian enterprise. He argues that humans think in concepts rather than words, and that no dictionary is able to provide equivalents between any two given languages as no two words conventionally regarded as translations of each other can ever refer to the same objects. Others have made a similar point by talking of the language of thought, or mentalese, a non-verbal code processed by the human brain.

According to this theory, to be able to translate accurately you need a thesaurus with a comprehensive list of synonyms for each entry, as well as examples of each word’s use in every context imaginable. Then, provided the other party has a similar reference book containing not merely words but experiences, you might be able to find the exact correspondence between the two. Unless such compendiums are available, perfect translation is a fantasy (and so, by the same logic, are writing, reading, speaking and indeed all intellectual endeavors). In this light, translation may appear to be an unsolvable problem, yet it’s worth tackling, especially given the evidence that communication in more than one language is, after all, possible. It can be effected in infinite ways, though word-for-word translation is seldom one of them. Things would be different in the ideal world, where every word would have the perfect match in every dictionary, every sentence would be clearly written and every message carefully enunciated. Our world is not like that—and so much the better.

Can translators take liberties? Should they? The nature of the job, as we are about to see, means that interventions are hard to avoid.

The translator’s real concern is not words but sense. To preserve it, you can smooth the original’s strange features to make the meaning more accessible, or you can retain some foreign notes in your translation, ensuring that it comes across as such. Do these approaches have to be mutually exclusive? A hint lies in the way translation as a practice is defined. It can be considered an art, a craft, a pastime, a hobby, a necessity, depending on what motivates those engaged in it. It can be as creative as you make it, but it is also a secondary activity: the original has to be there first. It can be a vocation, a calling, a main occupation, but also a sideline, something to fall back on when you need a break from your other job, when you are desperate for some new experience or just desperate. Translators have often doubled as poets, slaves, doctors, apprentices, lawyers, spies, preachers, diplomats, soldiers, and so on. “So let us say that translation is a trade, like cabinet-making or baking or masonry,” the writer and translator Eliot Weinberger proposes. “It is a trade that any amateur can do, but professionals do better.”

Translation, therefore, is a job like any other, driven by supply and demand; something you can be inspired by or simply do for a living, taking things on as they come: a divorce case or an experimental novel, a car manual or a holiday brochure. As you go about your task, your actions can change the world around you in more ways than you expect. This book will talk about translators doing things that, while not being part of their official remit, shape the way they approach their job. It will talk about the quality of translators’ work, an elusive concept, and look into the relationships between translators and those who need them, something made especially complex by inevitable gaps in mutual comprehension. Finally, it will give a glimpse of the future—not too distant it seems—when translators may have to grow even more versatile in order to compete with machines.

The stories collected here show translators at work, describe what they do and what happens next: concrete actions and their consequences, momentous or otherwise. As for theory, it’s the province of the translation police (as the more dogmatic among translation studies scholars are known in the trade), who see it as their task to enforce rules, from linguistic to ethical to political. These people are part of the translation ecosystem but not of this book. It is about those who, rather than lurching between abstractions, take the plunge, hoping to solve a problem that may or may not have a solution. What keeps them awake at night is not the thought of how feasible translation is, but the question of how to translate a particular idiom, treatise, poem, address, novel, judgement, joke; to make it intelligible while preserving both the letter and the spirit; to get at its meaning; to make it work.

If translation is about finding a space between gaps, or a compromise between meanings, how best to perform this balancing act? “It is almost impossible to translate verbally, and well, at the same time,” John Dryden wrote in 1680 in the preface to his translation of Ovid’s Epistles.

In short, the verbal copier is encumbered with so many difficulties at once, that he can never disentangle himself from all. He is to consider at the same time the thought of his author, and his words, and to find out the counterpart to each in another language; and besides this, he is to confine himself to the compass of numbers, and the slavery of rhyme.

After giving the matter careful thought, Dryden delivers his verdict, still valid today:

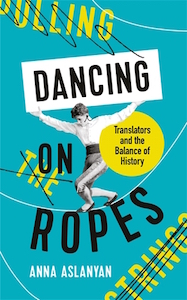

It is much like dancing on ropes with fettered legs: a man may shun a fall by using caution, but the gracefulness of motion is not to be expected; and when we have said the best of it, it is but a foolish task; for no sober man would put himself into a danger for the applause of escaping without breaking his neck.

A figure dancing on a rope, with its joyful as well as sinister connotations, is an apt image for the profession. Translators must simultaneously work towards several goals: to get the message across and not to break certain constraints, to stay upright and to maintain flexibility. To keep everything in balance, they constantly move between these near impossibilities, and the world moves with them.

_________________________________________

Extracted from Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History by Anna Aslanyan, published by Profile Books.

Anna Aslanyan

Anna Aslanyan is a journalist, literary translator and public service interpreter. She grew up in Moscow, lives in London, and feels most at home in books.