On the Difficulty of Narrating the Audiobook for Your Own Memoir

Freda Love Smith Admits, "It's Kind of Hard to Read"

This is the most familiar thing in the world, the engineer’s voice in my headphones, me in the sound booth, him at the board. I’ve spent hundreds of hours in recording studios, tracking drums, and I’m accustomed to taking direction and criticism: you were dragging behind the click; your energy was low; you hit the cymbals too hard there, back off. Now, as usual, the engineer listens carefully and keeps me on track: “I heard some throat noise,” he says. “Let’s take it back to ‘I am very much a person…’” This time, the microphone isn’t pointed at my hands and feet but at my mouth: I’ve been hired to narrate an audiobook.

He plays back the sentence before I’m supposed to jump in, and I cringe, the clashing horror of recognition and strangeness—that’s me? That’s what my voice sounds like? It’s never the way I think I sound, the way I sound in my own head. It’s maybe getting a little easier after two days in here, but I can’t imagine ever not hating that sound.

“I am very much a person who likes to get high,” I read. “I have always been a person who likes to get high.” I try to feel the words, not just recite them, try to convincingly perform this rueful confession of the author, documenting her struggles with addiction and her mixed feelings about intoxication. The book is fragmented, potty-mouthed, decidedly inconclusive, laced with literary references and sociological research and vomiting scenes. It’s kind of hard to read.

Also, it’s mine. It’s my book. I wrote this thing. It’s me.

Or it was me; me a few years ago. As I read back my words I feel the slipperiness of time, the way a memoir is a snapshot that pins us to moments in our lives and the way that time rolls ceaselessly. It’s a powerful, felt experience of the Buddhist concept of impermanence, described by Pema Condron in How We Live is How We Die, one of the many books I refer to in mine: “Things are constantly coming to an end, and things are constantly coming into being…We’re under the illusion that life will stay similar to how it is now.” Narrating my book wrecks that illusion. I try to cultivate empathy and tenderness for a three-years-ago version of myself. She was a mess.

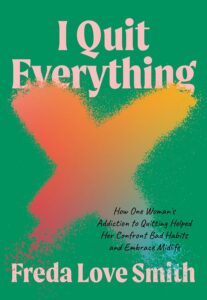

This experience of time travel chimes with the parts of my book where I dig back into the cultural touchstones of my childhood, an attempt to better understand my present self, a search for clues about why I am the way I am. Investigating my deep-set feelings for alcohol, I discover that my younger self had been, “inextricably drawn to stories of unrepentant souses.” I narrate that line vigorously, articulating each syllable of “unrepentant” before I ramble on for many pages about The Bad News Bears. I love movies about drunks and druggies: Bad Santa. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Impermanence is real. But so are patterns and tendencies. My memoir, I Quit Everything, is about how I quit booze and weed and sugar and caffeine and social media. A later chapter, though, is titled “I Quit Quitting.”

*

In addition to the engineer in my headphones, we have patched in the audiobook director from his home, so there are two attentive listeners here. They are professional and supportive—kind, even— and yet I frequently feel self-conscious about what I’m reading to these two men. When I was a drummer, I enjoyed more emotional distance—I didn’t write the songs, didn’t have to sing them. But there are no drums to hide behind here. And it was one thing to write about sex and middle age and cannabis—it is another to speak about it without fumbling or giggling or apologizing, maintaining a clear, steady voice. I force myself to read perfectly during the most personal, vulnerable parts; I will not make the engineer say, “Let’s take it back to ‘extra lube.’”

It’s my book. I wrote this thing. It’s me.

It helps that I’ve already read the entire book to someone. I spent a sweet, cozy weekend in the home of my brilliant friend, the writer Maryse Meijer, reading aloud to her, stopping when we noticed something jarring or out of synch, filling in spaces that needed filling. I’ve both received and dispensed the common advice to writers: read your work out loud! But that was the first time I’d ever read an unfinished project to someone else, and it was one of the most valuable writing experiences of my life. Now, when I’m in the late stages with a piece, I pretend to read it to Maryse, my ideal editor: generous, smart, attentive, and frank.

That weekend was a joy: I don’t feel the same joy now—now it’s too late to make this thing better. Some of the sentences sing in tune, others fall flat. I can’t fix them. It’s done; it’s dead, in a way. It’ll be published in a couple of weeks, and everyone might hate it and there’s nothing I can do. I’ve always had a bizarre resistance to listening back to an album after it’s finished, always afraid to hear my drumming, never as tight and musical as I aimed for. Sometimes I hear only the effort, the struggle, the repeated takes, the failed attempts at perfection. Like Caedmon’s hymn, described by Ben Lerner in The Hatred of Poetry—the hymn presented itself to him in a dream, a gift from God, incredibly beautiful, otherworldly, but when he awoke and sang it, something was lost, it wasn’t the same.

Nothing we create is ever as good as we dreamed it would be.

The me who wrote a memoir about quitting; I’m her and I’m not her. I think about why I wanted to write this strange and personal little book and I feel my voice catch as I read aloud about the death of my friend Faith, the grief not as raw but still real. I recall something I’ve shared with many of my writing students, from Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones. “The problem is we think we exist,” writes Goldberg in the chapter “We Are Not the Poem.” She describes reading her poems to strangers, realizing that they think the poems are her. “Watch yourself,” she warns. “Every minute we change.”

Goldberg offers one way forward: “At any point, we can step out of our frozen selves and our ideas and begin fresh. That is how writing is. Instead of freezing us, it frees us.” Work hard with all your heart, she advises, and then cultivate a healthy sense of detachment: “Write good poems and let go of them. Publish them, read them, go on writing.”

I come to the end of my audiobook: “You can’t quit being yourself,” I say. That bit rings true, and I perform it with conviction. The work is done. I’ll never listen to it; I won’t be able to bear the sound of my voice, the foreignness of that “I” character, the imperfection of the prose. And future me will be busy, anyway, hard at work, I hope, going on: writing, entangled in the next beautiful cycle of dreaming and disappointment.

__________________________________

Freda Love Smith’s memoir I Quit Everything is available from Agate.

Freda Love Smith

Freda Love Smith is a writer, teacher, and retired indie rock drummer. Her first book, Red Velvet Underground, was published in 2015. She teaches at Northwestern University and Lesley University, and she played drums with Blake Babies, Antenna, Mysteries of Life, Gentleman Caller, Some Girls, and Sunshine Boys. Freda reviews nonfiction for Booklist, writes for the Sound of our Town podcast, and is the programming director of Bookends University, the curricular arm of Bookends & Beginnings bookstore in Evanston, IL.