On the Build-Up to the Legendary Baldwin-Buckley Debates

Bad Reviews, Disastrous Elections, and the Intellectual State of Play in 1964 New York

On Monday, January 4th, Bill Kolins, a publicist at Corgi Books in London, called Robert Lantz, James Baldwin’s agent, to present him with a proposition. Corgi was set to publish the paperback version of Another Country in the United Kingdom in February, and Kolins wanted to launch the book with a bang. With Baldwin’s star power at an all-time high, Corgi proposed to orchestrate the most extensive publicity campaign in its history.

The goal, Kolins explained, would be to bring Baldwin to London for the release of the book and saturate the media landscape with his presence for several days. Kolins envisioned print advertisements, public talks, interviews, and receptions. Baldwin was, at that moment, one of the biggest literary celebrities in the world, and Corgi wanted to give him the star treatment and, of course, sell books.

Lantz called Baldwin, who was back in France, to see if he would be up for a trip to the United Kingdom. Baldwin agreed in principle even though he was—and had been for some time—quite ill with a series of viral infections that often left him bedridden. Baldwin’s physical symptoms were coupled with a deep spiritual malaise. In August 1964, Baldwin marked his 40th birthday with a sense of uncertainty about his personal and professional life.

On the personal front, the love of his life, Lucien Happersberger, had fallen for Diana Sands, the actress playing Juanita in the Broadway run of Blues for Mister Charlie, and the frenetic pace of Baldwin’s life made it difficult for him to sustain meaningful contact with the same group of friends and family for long. Baldwin had many friends in many places, but his transatlantic commuting took a toll on his relationships, and it was next to impossible for him to ever feel at home.

On the professional front, Baldwin—though at the height of his fame—was now the target of more virulent criticism than he had ever faced. Another Country was met with mixed reviews, and the book’s explicit sexuality and drug use made it a subject of controversy on campuses and in communities throughout the United States. With the arrival of Blues for Mister Charlie on Broadway, Baldwin fulfilled a long-held dream of seeing one of his plays reach the pinnacle of the theater scene, but the production was rife with offstage drama.

When the play opened in April, it was also met with mixed reviews, including an especially harmful dig at Baldwin by the writer Philip Roth, who panned the play in the New York Review of Books. After the tumultuous preproduction, lukewarm critical reception, and financial difficulties due to Baldwin’s insistence that ticket prices be kept low, the producers gave the show notice of closing only one month after it opened. A group of artists and philanthropists rallied to raise money to keep the play running for a few more months, but the Broadway run closed for good on August 29th.

In December 1964, Nothing Personal was the subject of a brutal review by the critic Robert Brustein in the New York Review of Books. Brustein had issues with the book itself—he thought that Avedon’s photographs transformed his subjects into “repulsive knaves, fools, and lunatics,” and said Baldwin’s prose sounded like it came from “a punchy and pugnacious drunk awakening from a boozy doze during a stag movie”—but perhaps more disturbing, he saw the book as a sign of Baldwin’s artistic decline. Baldwin, Brustein declared, had once been a source of “direct and biting criticism of American life,” but this “once courageous and beautiful dissent” had degenerated into the “slippery prose” of a “showbiz moralist.”

In addition to these personal and professional woes, Baldwin was concerned about the fate of the world. Although there was some hope to be found in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Johnson’s landslide victory over Goldwater, the recent violence in the South and Harlem were merely the most blatant manifestations of the enduring sickness of the American soul. In early August, Baldwin issued a statement to the New York Post about the riots in Harlem. He noted that the only people who were not surprised by the events were the residents of Harlem and other northern ghettos.

While Baldwin attempted to recover physically and spiritually in the south of France, William Buckley was undertaking a restorative project of his own.

These people, Baldwin reminded his readers, experience a demoralizing “contrast” every day when they make their way from the “intolerable conditions” under which they live to “the white world” in which most of them work. Those Americans who are not trapped in the ghetto are able to avert their eyes from these conditions and remain ignorant of those who experience them every day. In addition, Baldwin said the people of Harlem had little reason to “respect the Law” because it was “overwhelmingly clear” that “the Law” had “no respect for them.”

Instead of blaming militant leaders and Communists for civil disorder, Baldwin urged his readers to think about the impact of “the rise of Governor Wallace and still more the candidacy of Senator Goldwater” on the morale of marginalized people. The Johnson victories over Wallace and Goldwater, though welcome news, did not vanquish the “forces responsible for this despair and common danger.”

*

After Lantz received Baldwin’s consent, he wrote to Kolins at Corgi Books: “Mr. Baldwin will be happy to make the trip” to London, but he will “do only major interviews, and possibly one reception at which he could meet not only press people, but also other distinguished writers.” Lantz also requested that Corgi arrange to fly Baldwin’s sister, Gloria Davis, from New York to London to accompany him on the tour.

Davis was then in her brother’s employ, and he liked to have her as company during his travels. “You need someone to get you going places,” he explained to a biographer, “to keep your appointments, you know, to—act as a buffer between you and the world.” Corgi agreed to this arrangement, and Kolins got to work setting up many appointments for Davis to help her brother keep.

*

While Baldwin attempted to recover physically and spiritually in the south of France, William Buckley was undertaking a restorative project of his own. In the wake of the Goldwater defeat, he used his voice and pen to argue against the idea that the landslide marked the death of the conservative movement. In making this case, Buckley had to walk some fine lines. He still held Goldwater in high regard, but he thought the campaign was disastrous. Some of this, of course, was a result of what Buckley viewed as shameful fearmongering by Goldwater’s critics, who successfully prevented an intellectually serious exchange of liberal versus conservative ideas by reframing the race as one of crazed fanaticism (Goldwater) versus the relatively sane status quo (Johnson).

But Goldwater’s enemies were not the only ones to blame, Buckley argued. Some responsibility belonged to the candidate himself and, of course, his “political counselors.” In one postelection speech, Buckley referred to the “glorious ineptitude” revealed by Goldwater’s willingness do things such as rail against Medicare while among the retirees of Florida and criticize the Tennessee Valley Authority while in the bosom of Tennessee. Given the unfair accusations against Goldwater from the Left, and impolitic habits of the candidate and his handlers, it would be a mistake, Buckley contended, to view the election result as a referendum on conservatism.

As Buckley looked ahead, racial issues were still at the forefront of his mind. The December 1st, 1964, issue of National Review provided readers with a “Special Report” on “What Now for Republicans?” and a series of essays in which “Leading Conservatives Discuss the Future,” but the feature cover story in the issue was announced in big, bold print: “NEGROES, INTELLIGENCE, AND PREJUDICE” by Ernest van den Haag.

Van den Haag, a conservative sociologist at Fordham University who bore a striking resemblance to the title character in the recent hit film Dr. Strangelove, was a regular contributor to National Review and friend of Buckley’s. He had been called as an expert witness to discuss the “sociological-psychological impact of segregation” in the South, and his ideas so pleased the Citizens’ Council that it asked him to summarize his testimony on its television program. Buckley had long championed van den Haag’s pseudoscientific work on race, even devoting a full-page paean to it in a 1961 issue of National Review.

In his 1964 piece, van den Haag used a tongue-in-cheek, question-and-answer format to offer criticisms of liberal social scientists who seemed more driven by “egalitarian ideologies” than by scientific truth. It is a bizarre piece of writing thanks in part to the question-and-answer format, but the overall thrust of the argument was this: social scientists should not be afraid to establish criteria for evaluating human beings, determine the differences between racial groups based on that criteria, report the racial differences captured by their results, and prescribe appropriate policy changes based on their findings.

Among other things, van den Haag concluded “at least for the time being, the needs of Negro children would be best met . . . by separate education geared to meet the obstacles presented by lack of opportunity and unfavorable environment.” It is no wonder the Citizens’ Council greeted van den Haag’s ideas with such enthusiasm.

The right of white southerners to govern themselves was sacrosanct, and it was perfectly understandable to Buckley . . . that those with this power would be willing to kill if they sensed it was slipping away.

In an issue that was focused on the future of conservatism, it may seem surprising that Buckley made the editorial choice to feature this provocative piece by van den Haag. Buckley sensed that the essay was likely to ruffle some feathers so he circulated it all over town to intellectuals such as Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol to invite them to respond to van den Haag in print. There was something about the van den Haag piece that Buckley thought was extremely important, but he did not provide a definitive explanation as to why that might be the case.

One possibility is that Buckley saw the piece as a fitting follow-up to the “Special Report” on the “Race Issue” he had commissioned only months earlier. The theme of that series—with the exception of the Wills piece, which was more nuanced—was that whites were lashing back against the excesses of racial egalitarianism because they resented being told that their privilege was the result of racist legal and social practices. Buckley enlisted van den Haag to tell these aggrieved whites that there was a social scientific basis for their indignation. They were being accused of racial prejudice when in fact, van den Haag was telling them, their desire for separation was justified by “scientific truth.”

The intellectuals to whom Buckley sent the piece were not impressed. Bell, who was a distinguished sociologist at Columbia, asked Buckley, in effect, Where are you going with this, Bill? “The existence of any genetically-determined differences between races . . . ,” he told Buckley, “has little bearing on the social and moral treatment of members of different races.” Kristol, then an editor at Basic Books, called the van den Haag piece thoroughly “ideological” and suggested to Buckley that “the evidence for an average lower intelligence among Negroes is probably no stronger than the evidence of an average higher intelligence among Jews. So what? The evidence is skimpy; its implications, dubious.”

A few weeks after the van den Haag piece was published, Buckley used the space of his column to weigh in on recent events in Mississippi, where a second jury failed to convict Beckwith, whose fingerprints were found on the gun that was used in the assassination of Evers. In addition, local officials were resisting a federal push to prosecute 21 individuals thought to have played some role in the murder of civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

Buckley acknowledged that there seemed to be “precious little” justice in Mississippi “when white people persecute black people,” and the state had “a despicable record of indifference to crime and humiliation.” “The trouble,” Buckley argued, is that “there are jurors in the South who do not recognize that a crime against a Negro falls under the generic category of ‘crime.’” This was a problem, but it was not immediately obvious to Buckley what ought to be done about it. One thing that should notbe done, he insisted, was to empower the federal government to intervene to promote greater justice for African Americans.

To do so, Buckley maintained, would be to infringe on “the best part of Southern life”: the right of white southerners to govern themselves. Remarkably, Buckley’s arguments on this front were almost identical to what they had been when he launched the magazine nearly a decade earlier. We ought to “deeply distrust government’s assumption of any great power” because decentralization, he continued to assert, was an essential safeguard of liberty, the experiences of southern blacks and slain civil rights workers notwithstanding.

Would Baldwin be willing to participate in a debate on a “motion which reflected the themes of his writing?”

With federal coercion off the table as a legitimate option, Buckley suggested that the best approach might be “communication” with the “decent citizens” of Mississippi. Alas, the channels of communication had been gummed up by “fanatical egalitarianism” and “abstract moralizing” by “the Federal Government and the Supreme Court and the moral intelligentsia,” who “have no understanding of the best part of Southern life—the part that caused William Faulkner . . . to say that he would take up a rifle and shoot any federal marshal whose presence challenged Mississippi’s right to govern itself.”

Like his celebration of Faulkner when he uttered these words nearly a decade earlier, Buckley had nary a word of criticism to say about them. This is not surprising since he thought Faulkner was basically justified. The right of white southerners to govern themselves was sacrosanct, and it was perfectly understandable to Buckley—though not completely defensible—that those with this power would be willing to kill if they sensed it was slipping away.

•

Buckley and Baldwin may have never met were it not for the persistence and insubordination of Kolins, the publicist assigned to promote Another Country for Corgi Books. Although Baldwin’s agent, Lantz, had agreed to a tour that would include only limited engagements, Kolins was determined to develop a far more robust itinerary. During the first week of January, he began working the phones to fill every nook and cranny of Baldwin’s week in London. Somewhat naughtily, he seems to have kept the details of the itinerary hidden from Lantz and Davis until the last minute.

One of Kolins’s phone calls in January went to the Cambridge Union in order to see if it might be willing to host Baldwin. Peter Fullerton, an undergraduate studying history and Union president at the time, told Kolins that he was unwilling to host Baldwin for a mere book promotion event. The Union, he explained, was a debating society so it would be an inappropriate venue for such an event. But Fullerton was not about to let the opportunity to host Baldwin pass the Union by so he presented Kolins with a counterproposal: Would Baldwin be willing to participate in a debate on a “motion which reflected the themes of his writing?”

Kolins tentatively accepted this counterproposal, Fullerton explained later, without really knowing what he was committing his client to do. The precise details of where they left their phone call are lost to history, but it seems likely that Fullerton pledged to work out particulars—a date, opponent, and motion—and share them with Kolins as they became available.

While Kolins was making big plans for Baldwin’s trip to London, the famous author was sick in bed. On January 12th, biographer David Leeming notes, Baldwin’s “fever had reached its rather alarming peak,” and his sense of his own mortality was heightened by the news that his friend Hansberry had succumbed to pancreatic cancer at the age of only 34. About a week later, Kolins shared flight and hotel details with Lantz, who in turn sent them on to Baldwin and Davis.

During the last week of January, Davis reached out to Kolins directly to thank him for making the travel arrangements and request a more detailed itinerary for the week. She made sure to let Kolins know about Baldwin’s fragile health and expressed concern about overcommitting him on the tour. She put her trust in Kolins to exercise restraint in putting together Baldwin’s schedule.

Kolins does not seem to have been fazed by the requests from Lantz and Davis to keep Baldwin’s itinerary light. He was, after all, a publicist. His primary concern was to get Baldwin as much exposure to the British public as possible. And so he carried on finalizing details for press conferences, television interviews, receptions, and appearances at Cambridge and Oxford.

__________________________________

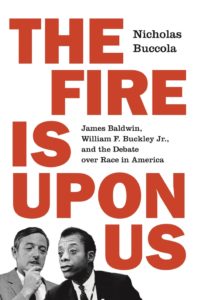

Excerpted from The Fire Is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America by Nicholas Buccola. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Nicholas Buccola

Nicholas Buccola is the author of The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass and the editor of The Essential Douglass and Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, and many other publications. He is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, and lives in Portland.