On the Black Descendants of Thomas Jefferson and Uncovering the Origins of Family Lore

Gayle Jessup White Considers What It Means to Remember the Past

There are at least two known burial grounds at Monticello, the estate that was Thomas Jefferson’s home. One is near the main house and surrounded by an imposing wrought iron fence. It is populated with tombstones marked “Jefferson,” “Randolph,” “Taylor,” and the surnames of other kin. Jefferson’s grave is marked by an obelisk adorned with an inscription of how he wished to be remembered:

HERE WAS BURIED

THOMAS JEFFERSON

AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

& FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA

The graveyard is still in use. It is the only property on the former plantation not owned by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, the nonprofit that owns and manages Monticello, but by a group called the Monticello Association, whose members are direct descendants of Thomas Jefferson and his wife, Martha Wayles Skelton. From time to time, members of the association gather for a burial or a wreath-laying ceremony to commemorate their legendary ancestor. Only Jefferson, his white family, and their descendants and spouses are buried there. Only they are welcome. That was made painfully clear a few years after a white descendant invited dozens of his Black cousins to an association reunion. They were guests because they too can trace their origins to the third president.

They were descendants of a liaison between Jefferson and a woman he enslaved, Sally Hemings. In 1999, as the cousins, white and Black, mingled cordially at Monticello and at lunches and cocktail parties, the media followed. The news reports that followed made reconciliation seem possible, even imminent. But three years later when the same white cousin who had orchestrated the reunion sought membership for his Black kin, they were shut out.

According to witnesses in 2002 when a vote was taken at the association’s annual meeting, a near-riot erupted as white members, fueled by two centuries of denial about who fathered Hemings’s children, furiously objected. The episode made the national press. “There was my family being racist on the front page of the New York Times,” lamented a white descendant 20 years later.

A short walk down the mountain along a gravel path and near the entrance of Monticello’s Visitor Center is another gravesite. Bordered by a parking lot, a few trees, and wooden rail fencing is a burial ground for those who were enslaved on Jefferson’s plantation. Here are no obelisks or tombstones, only large rocks marking where people—my people—are buried. No one knows the names of those interred there, only that they were enslaved at Monticello.

The burial ground, like much of African American history, was almost lost forever.

What saved it was an oral tradition, which for centuries was how America’s Blacks remembered their past. The story goes that when old-timers who had spent their lives living in the shadows of Jefferson’s mountain heard that the graveyard was to become a parking lot, they spoke up. They knew bodies were buried there because their mothers and fathers, who had heard it from their mothers and fathers, said it was so.

We can only speculate about who might be buried there. Perhaps Ursula Granger, whose reputation as a great cook induced Jefferson to purchase her at his wife’s request in 1773. It was Ursula’s breast milk that saved the life of the couple’s sickly six-month-old daughter, named Martha after her mother, when her ailing mother was unable to nurse her. Were it not for Ursula I would not be here, because the child she saved would become my great-grandmother four times over. Or skilled worker Cate Hubbard, my four-times-great-grandmother. Two of her sons were among Monticello’s few “runaways.”

What saved it was an oral tradition, which for centuries was how America’s Blacks remembered their past.

Or Elizabeth Hemings, who came to Monticello with her ten children when Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles, died in 1773. Elizabeth’s remains might rest near her cabin or the burial ground, but we will never know. Though they were human beings, they were treated like property, passed down to Wayles’s daughter Martha as part of her inheritance, just like money, land, and livestock. However, the Hemings clan was linked to Martha by an unacknowledged kinship. Wayles was the father of six of Elizabeth Hemings’s children, including the infant girl Sally. They were Martha’s half-siblings, and in a different world they would have been considered Jefferson’s in-laws.

Hundreds of Black people spent their entire lives held captive on a 5,000-acre plot of mountainous land laboring, as Jefferson put it, for his “happiness” while trying to carve out some happiness of their own.

Aside from an inconspicuous panel describing whose remains may be inside the fencing of the enslaved graveyard, there is little to indicate that this space is hallowed ground. There have been reports that some visitors, assuming the site is a dog park, have allowed their pets to urinate on the trees next to the graves, oblivious to the history they were desecrating. Yet I am not oblivious to it. I can’t be.

The Jeffersons, Randolphs, and Taylors at the top of the mountain are as much my kin as the Hemingses and Hubbards whose remains might be at the bottom. But my heart rests with the souls in the graveyard of the enslaved. It is at their final resting place that I find solace and inspiration. It is their spirit that spurs me forward, even when I am feeling weary and battle-scarred after another day spent fighting for equal recognition of Black history that for many is merely an afterthought.

The gravel path from the enslaved at the bottom of the mountain to the enslavers at the top is less than a mile long. But the chasm this distance symbolizes is as deep and dark as the ship hulls that carried human cargo across the Atlantic during the Middle Passage. It began more than 400 years ago when the first captured Africans were brought to the British colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. A complex entanglement between Blacks and whites also emerged, one that has left virtually all African Americans with European DNA.

There are few places where those woven relationships are as well chronicled as those that existed at Monticello. At least four generations of Hemingses had close relations with Jefferson family members, from his father-in-law to his great-great-grandson, the man who became my great-grandfather.

I did not grow up knowing this history. In fact, like many Americans I was not taught that the principal author of the Declaration of Independence—the man who declared that all men are created equal—owned human beings. However, from the moment I learned the family lore that we are Jefferson descendants, I was intrigued by the mystery of our family’s origins and set out to try to uncover the truth. Sometimes intentional, sometimes not, I have made choices throughout my life that brought me to where I am today—to Monticello, the epicenter of the American paradox—and of my family’s story.

While some might have been repelled by a place where their ancestors were enslaved, I was drawn to it. From my very first visit to the plantation, I knew I wanted to work there. I was in my early forties—no youngster—when I finally took the time for the two-hour drive from my home in Washington, DC, to Charlottesville, Virginia. It was the spring in 2004, and until then I had always been too busy with school, then college and career, followed by marriage and family. But once I carved from my schedule two days to spend in Charlottesville, I was captivated by Monticello’s hypnotic beauty. The sun-kissed flower gardens and the winding paths beneath a cloudless blue canopy made it seem like I was strolling through a Monet or Renoir painting.

During that first visit, as I explored the home that Jefferson designed, I waited in vain for the guide to talk about the enslaved people who built the house. Their stories, I believed, reflected my own family’s and those of millions of people descended from the enslaved. That day in 2004 the questions sparked when I was an inquisitive child began to grow into something more compelling, something deeper, what activists might describe as a cause, and what the spiritual might define as a calling. That calling was the voice of my ancestors demanding to be heard and imploring me to be their spokesperson. That calling was my ancestors guiding me to confirm the family lore and reclaim our place in American history. That calling was my destiny.

What started for me as a sheltered 13-year-old’s curiosity about my family’s unproven ties to Thomas Jefferson became a passionate cause, and finally an unlikely late-life career.

My 50-year-long journey began in a cloistered community in Washington, DC, called Eastland Gardens. The neighborhood was distinct, for it was one of few in the nation designed, built, and owned by Blacks.

__________________________________

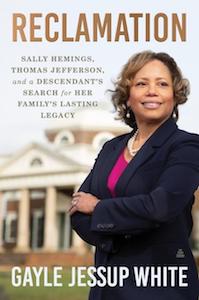

Excerpted from Reclamation: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and a Descendant’s Search for Her Family’s Lasting Legacy. Used with the permission of the publisher, Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Gayle Jessup White.

Gayle Jessup White

Gayle Jessup White is the Public Relations & Community Engagement Officer at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s legendary estate. A former award-winning television reporter and anchor, Jessup White started her career at the New York Times. She’s written and spoken extensively about her work at Monticello. She is a direct Jefferson descendant, and is also related to two well-documented families enslaved at Monticello—the Hemingses and the Hubbards.