On Sick Trees, JD Vance, and the Invasive Species of Appalachia

Leah Hampton: "Appalachia is insanely complex, and its destruction has been muddy and tangled."

I am spending the pandemic worrying about trees. Or, specifically, one tree—an Eastern hemlock who lives in our yard. I have named her Harriet; she is fifty feet tall, and she is very sick. Every day I talk to Harriet. I talk about current events, maybe read her a few tweets. I talk about how much I want her to survive this difficult time, and about how pretty she looks, even now, with her limbs empty and pale. Nobody, not my hipster Asheville friends, or the crazy chicken lady at the bottom of our road, or the local boys who snicker at “tree huggers,” thinks I’m weird for talking to her. We all have Harriets; no one judges.

Harriet has a disease we know intimately here: woolly adelgid. An invasive pest, the woolly adelgid has, in only a few decades, systematically destroyed millions of native hemlocks in the forests of Appalachia. Woolly adelgids are bugs, tiny evil sap suckers that can denude a hundred-foot tree faster than any biologist or park ranger can treat the blight. At this rate, extinction is a near certainty. Drive our country roads at high elevation, and you will see the woolly adelgid’s aftermath. Ghost trees, we call them. Majestic, ancient ents, once lush and towering above other species, their trunks now stand lifeless and naked, ravaged by infestation. Ghost hemlocks look like creepy, gnarled telephone poles poking out of the ridgeline, like walking sticks or canes. Like loss.

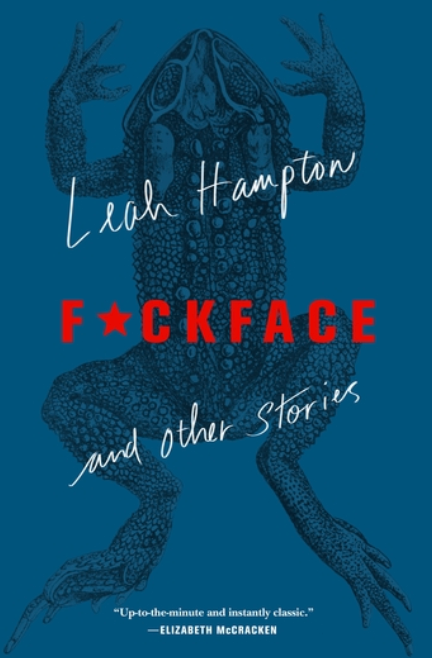

My husband and I have lived in our house near the Great Smoky Mountains National Park for over a decade now, and Harriet has always been the picture of health, our best and favorite tree. In this house, I started my first book, F*ckface and Other Stories, with the intention of capturing 21st-century rural life in all its hilarity, modernity, and heartbreaking strangeness. We converted the dining room into an office, and there I wrote, occasionally eyeing Harriet out the window. Hemlock branches were once used as soft-bristle brooms; their boughs are heavy, their needles silky and fine. In her prime, Harriet was so thick with delicate evergreen fronds that she kept both snow and sun from ever touching our roof. I used to brag about her. I used to tell people she would never get sick, that a guy from the Cooperative Extension said she was the best specimen in the county. I wrote a whole book in her shadow.

On our land, there are bears, poplars, rhododendron, snake, opossum, owl. I write about them in F*ckface. Everything is beautiful. This is the life, we often say. Deer and wild turkey visit us, groundhogs snuffle in our unkempt yard. In summer, our house is surrounded by the fairy magic of fireflies wooing each other in the dark. In winter the woodpeckers watch us, black eyed and perturbed. Woodpeckers spook me. They are a keystone species, and they stare at our house so fixedly, as if telling us we don’t belong.

They’re probably right. Despite its beauty, its varied and teeming life, Appalachia is rife with invaders, and the resulting slaughter, of my hemlock and so much more, is our fault. Environmental crises abound here, and I write about those in my book, too. The first pioneers started it when they brought foreign crops and livestock into the foothills. Then came the coal and timber industries, rampant habitat destruction, Cherokee Removal, capitalism, racism, fascism, tourism. Two hundred years of suppurating infection and unbridled theft. Once the oldest and most biodiverse ecosystem on the continent, Appalachia is now on life support, suffering from an insidious macro-sickness too complex and overpowering to comprehend. The effects are irreversible, debilitating—a virus of the whole body which manifests in a million Harriets, a billion small, inexplicable hells.

Extinction is not a simple or predictable process. Appalachia is insanely complex, and its destruction has been muddy and tangled.

Those who traffic in harmful stereotypes about Appalachia will tell you that this illness is a moral crisis, not an environmental one, that market forces or “progress” will fix the place. Much has already been said against JD Vance, for example, the author of the bestselling Hillbilly Elegy. Historian Elizabeth Catte does a much better job than I can of dismissing Vance’s bullshit, so I’ll simply say this: guys like Vance, or anyone who tells you that rural spaces are occupied by poor, dumb folks who deserve their threatened landscape, are the worst kind of pestilence. Vance’s account of Appalachia is white supremacist nonsense, but for whatever reason, people, even liberals, bought it. He made a lot of money off Elegy, and is now the darling of conservative think tanks. When an invasive pest arrives, it comes only to feed, to profit and upset the balance. Such creatures ignore our diversity—both cultural and biological—and see it as an obstacle to stuffing their own bloated carcasses.

Extinction is not a simple or predictable process. Appalachia is insanely complex, and its destruction has been muddy and tangled. The ecological threat is not just little bugs like the woolly adelgids, either. It’s everything that isn’t indigenous, anything not operating in harmony with this place, and the exponential holocausts that result from all of us, you and me, fucking with paradise.

It’s kudzu, for starters. Callery pear, honeysuckle, coyote. Things we brought here for convenient or selfish reasons, intruders who take without asking. Ladybugs, Thousand Canker, ash borer, fire ants. Gerrymandering, corporate tax evasion, labor exploitation, voter suppression. Floridians and JD Vance and underfunded schools and, I kid you not, self-cloning ticks. It’s about who stays and who goes, what gets preserved in a violated space. There are no easy solutions to environmental ruin. We did this to ourselves, and there is no vaccine.

Harriet the Hemlock. “Two years ago this branch was so thick you couldn’t see the sun through it.”

Harriet the Hemlock. “Two years ago this branch was so thick you couldn’t see the sun through it.”

To live in the Blue Ridge Mountains is to live in constant conversation with the land, and to understand these quandaries of invasion and removal. We extract, cultivate, love, abuse, and the land always answers. In addition to the trouble in the trees, ecological disasters affect human bodies, too. As I describe in my book, Appalachian people endure cancer clusters in coal towns and near chemical plants, the opioid crisis, the private prison industry, dying hospitals and farms. Everyone, even the Trump-tastic karens in their downtown condos, gets drawn into this dark dialogue, this disease of reckoning. Life in Appalachia is about symbiosis; thus, we have grown accustomed to concomitant death.

We act upon the land, and the land acts upon us.

This is the life.

Early in 2020 I spotted unmistakable fluffy white sacs hiding under Harriet’s branches. I took it as a personal failing. I had not been paying attention, and the woolly adelgids found her while I was distracted by selfish pursuits. I was busy finishing my book, swanning off to residencies and writers’ conferences, bragging about my mountain girl bona fides. I thought I was a champion of this place. But last fall the adelgids laid their eggs at the base of almost every needle, and by the time Covid-19 lockdown started, the bugs had begun to hatch and devour her. They had probably been there a while, eating her for a year or more, but I had failed to notice the signs. She is in a clearing, far from harm, I thought. She is old and strong.

Majestic, ancient ents, once lush and towering above other species, their trunks now stand lifeless and naked, ravaged by infestation.

Perhaps I shouldn’t blame myself or think myself special. Invasive species are global and legion. Look at Australia’s cane toads. Look at starlings, rabbits, Asian carp. Look at habitat loss and how it translates into disease, even pandemic. Look at what we’ve done. A long-lost friend of mine is an invasive species scientist in Hawai’i, and I often think of looking him up and asking him to take me to the William S. Merwin Conservancy. In the 1970s, Merwin and his wife bought twenty acres of disused land on Maui and started a palm forest. He searched tirelessly for endemic specimens and worked until his death in 2019 to bring thousands of tropical plants back from the brink. Such efforts won’t fix Hawai’i’s invasive blights, or preserve its coastlines from billionaires buying them up. So, what was the point, William? Most of us have read Merwin’s famous poem “Place,” in which he says, “On the last day of the world, I would want to plant a tree.” I think about that poem a lot these days, and I wish I could ask him, or my scientist friend, what to do about Harriet.

Advanced infestations of woolly adelgid are difficult to reverse. Eventually the bugs shut down the tree’s vascular system, until it can no longer breathe or carry nutrients to its remaining needles. The best treatments are preventive and require the tree to pull a remedy through its xylem, all the way from root to crown. Harriet could no longer do that. If I did not act, she would soon be a ghost.

In April, in desperation, I made the decision to soak Harriet with a heavy-duty pesticide. I won’t say the name of the chemical, because savvy environmentalists will recognize it and (rightfully) shame me. Suffice it to say this pesticide is illegal in several states and harmful to animals, especially if it finds groundwater. I did it myself, at least. I didn’t hire someone, did not subcontract the pollution of my own land. I had to wear protective gear and a mask when I covered her body with it. I showered twice afterwards, but the chemicals may have leeched into my skin, may yet, years from now, make me ill.

Poison. I gave her poison.

Please drink, Harriet. The medicine is bitter, but it’s the only thing that can save you.

What does that make me, I wonder? Am I the invader now, the pestilence, the villainous writer arguing cost-benefit, ends justifying her means?

By July my book was out, and I was giving interviews and virtual readings where I talked about myself, the region’s politics and history, eco-criticism, the big fancy questions of our time. As if I know the first thing about any of those subjects, as if I am not part of the problem, as the woodpeckers have suggested. But people seem to like F*ckface, seem to respond to its fatalistic humor and descriptions of nature. More importantly, Harriet is showing signs of regrowth. The white egg sacs are gone, and her branches are dotted with light green, tender needles. She is a big tree, so it will take at least two years to know whether the pesticide worked, or if it has damaged other species nearby—including me. I am optimistic. We talk every day, and I tell Harriet to hold on, to be the one hemlock who makes it, to live.

I say these things to her even though I can’t predict any long-term effects. If she does survive, what kind of life will Harriet have? I worry she will be scarred, that birds will refuse to nest in her tainted arms. I do not really know what I have given to her, or myself. But I hope—oh, in the midst of so much loss, so much collective mourning—how I hope it turns out to be a tiny light, a little cure.

____________________________________

Leah Hampton’s story collection, F*ckface, is available now from Henry Holt.

Leah Hampton

Leah Hampton is a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers and the winner of the University of Texas’s Keene Prize for Literature, as well as North Carolina’s James Hurst and Doris Betts prizes. Her work has appeared in storySouth, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Appalachian Heritage, North Carolina Literary Review, the Los Angeles Times, Ecotone, Electric Literature, and elsewhere. A former college instructor, Hampton lives in and writes about the Blue Ridge Mountains.