On Shakespeare's Two Heroic Friends that Saved the Bard's Plays From Being Burned

A Short History of the First Folio

It is the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, 29 June 1613. A fine sunny Saturday afternoon in midsummer, and the Globe Theatre in Southwark is packed. The play has just started. It’s called All is True, and we are about forty minutes in. Cardinal Wolsey, played (most likely) by the star of the King’s Men, Richard Burbage, is welcoming a fair company of ladies to York Place, his palace on the river, in what is now Whitehall.

The party is a rather tepid affair. Suddenly there is a loud explosion. A drum rattles out, trumpets sound and chambers are discharged. A barge has arrived carrying a troop of masked men, out for a good time. They are dressed as wild shepherds. The Cardinal, unaware that one of these gatecrashers is the young king, Henry VIII himself, in disguise, invites them to “take their pleasures.” As the musicians strike up, the king chooses a lady to dance with.

It is Anne Boleyn. Henry’s first words are a breathless aside:

“The fairest hand I ever touched! O Beauty, Till now I never knew thee.”

The audience knows that this encounter will ignite a spark that will set all England burning.

Indeed, the groundlings in the pit and gallants sitting on the stage are so enrapt that they fail to notice that when, on cue, the stage cannon was fired, some of the wadding landed in the thatched roof. What begins as a tell-tale wisp of smoke is soon a “fearful fire”, that tears around the straw thatch and sets alight the whole stage-house “as round as tailor’s clew.”[1]

An anonymous poem written at the time[2] laments that the conflagration soon:

“. . . burnt down both beam and snag, And did not spare the silken flag.”

The audience flee, losing hats and swords as they run. A man’s breeches catch fire, but someone douses them with his pot of ale. The poem recounts how Burbage and the actors escape too. Two of these “stage-strutters” are mentioned by name—one is Henry Condye (or Condell) and standing in the middle of the chaos is the distressed figure of “old stuttering Heminges.”

John Heminges is the company’s business manager, and he runs the tap house next door to the Globe. And although the anonymous eyewitness depicts Heminges in a flap, I suspect it might be quite the opposite.

The Globe fire takes place on a summer’s afternoon during a performance, and mercifully all the company are on hand to help rescue whatever properties and costumes they can carry. I think John Heminges, if he is “stuttering,” is in fact directing that operation, and falling over his words as he instructs his colleagues to rescue the company’s most precious commodity—their play scripts. When the rival Fortune Theatre, in Golden Lane just north of the Barbican, caught fire a few years later, it was in the middle of a wintery Sunday night in December. The prolific letter writer John Chamberlain wrote to a friend, “It was quite burned down in two hours, and all their apparel and playbooks lost, whereby those poor companions are quite undone.”

The Globe fire takes place on a summer’s afternoon during a performance, and mercifully all the company are on hand to help rescue whatever properties and costumes they can carry.

Of all the plays written for the King’s Men by their house playwright, William Shakespeare, only about half of them have been published, in the cheap paperback editions called quartos. The others exist only in handwritten manuscripts, and include Macbeth, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar and the plays he has most recently written, like today’s Henry VIII (or All is True) with his young collaborator, John Fletcher.

I imagine the actors carting what they have salvaged the mile or so across the river, to the Blackfriars, their indoor playhouse, where just three months before Shakespeare had purchased a property above the gatehouse of the old Dominican Priory. Perhaps they stack some of his smoky foul papers[3] and scorched fair copies there, half a writing career nearly turned to ash.

If Shakespeare had been re-energised by his new collaborator, and intended the gatehouse as a sort of London pied-à-terre close to his company’s winter home and to continue writing there, we have no evidence for it. Perhaps seeing the theatre where his greatest work had been performed turned to embers was too immense a blow for the writer. And although the theatre would be rebuilt and would open within a year (this time with a tiled roof), he never wrote for it again. It seems Shakespeare retired back to Stratford-upon-Avon, and not three years later was dead.

In his will, Shakespeare left twenty-six shillings and eight pence each to three of his friends and fellow actors: Burbage, Heminges and Condell, to buy mourning rings. Recent speculation has suggested that this was rather a request to memorialise their friendship and the body of work they accomplished together. And perhaps this was the trigger for Heminges and Condell (Burbage died in 1619) to gather all Shakespeare’s plays and publish them in a folio edition. After all, if his rival playwright Ben Jonson could do it (he published his collected works in 1616) then surely an edition of Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies would be an even greater commercial proposition.

If his rival playwright Ben Jonson could do it (he published his collected works in 1616) then surely an edition of Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies would be an even greater commercial proposition.

Until that moment, an avid theatre-goer who wanted to buy copies of plays by Shakespeare might have to do some traipsing about. They could buy Othello at The Eagle and Child, in the new exchange “Britain’s Bourse”, the shopping arcade recently opened in the Strand. They could walk up Fleet Street and buy Romeo and Juliet under the dial of St Dunstan’s, or A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the sign of The White Hart. In the precinct of St Paul’s Churchyard, in the north-east corner where a whole menagerie of booksellers had their stalls or stations, you could buy history plays (from Richard II to Henry VI) at the sign of The Fox, King Lear at The Pied Bull or The Merchant of Venice over at The Green Dragon.

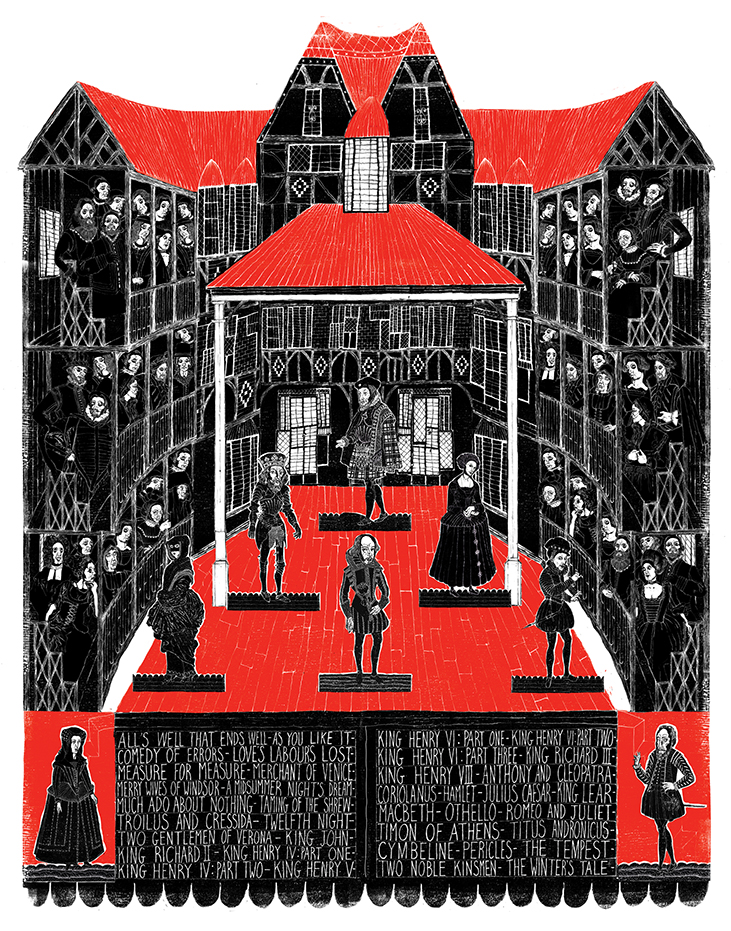

But in November 1623, at The Black Bear, Edward Blount’s station, by laying out twenty shillings you could buy all those plays, and eighteen previously unpublished, in a folio edition.[4]

Open the book and you will see a portrait of Shakespeare himself by the Flemish engraver Martin Droeshout; as well as a dedication by Ben Jonson describing his friend as the “Soul of the age,” “our star of poets” and as “not of an age but for all time”. And you may read a letter from Heminges and Condell “to the great variety of readers . . . from the most able to him that can but spell”. They eulogise their old colleague Shakespeare, “who as he was a most happy imitator of Nature was a most gentle expresser of it”.

But then they write, “For his wit could no more lie hid than it could be lost.” I would dispute that. For if these two men had not helped rescue manuscripts from the Globe fire (as conjectured here), had they not made the considerable effort of struggling to obtain the necessary copyrights, pulling together all his plays and publishing them in a single edition, we might indeed have lost most of the work of the playwright we consider to be the greatest writer in the history of mankind.[5]

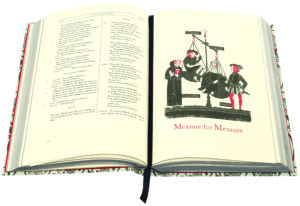

That is why we are celebrating this book four hundred years later, and the reason why The Folio Society are publishing this beautiful limited edition.

Without the First Folio we would have lost a world of words. We would not be able to reflect on the transient nature of existence, so succinctly expressed in the melancholy Jaques” philosophical metaphor “All the world’s a stage”. Or wonder at the fresh possibilities of life that Miranda perceives when she sighs, “O brave new world / That has such people in’t.”

Without the First Folio we would have lost a world of words.

We could not articulate any feeling of being insufficiently appreciated, or the courage to look beyond our circumstances with the coruscating disgust with which the exiled warrior Coriolanus turns his back on Rome, declaring, “There is a world elsewhere.” We would not be able to reach for so potent an example of ambition as quixotic and self-deluded as Brutus, as pathologically blinkered as Lady Macbeth or as pathetically humiliated as Malvolio.

Where would we find as vivid a depiction of the precipitous descent into morbid jealousy as in Leontes’: “Inch-thick, knee-deep, o’er head and ears a forked one?” Or a lack of perspective so complete as that of the philanthropist-turned-misanthrope Timon of Athens, of whom the cynic says, “The middle of humanity thou never knewst, but the extremity of both ends?”

Where else would we look to recognise a woman as pigeon-holed by the misogynist prejudices of her society as Katherina in The Taming of the Shrew? Or find a more acute characterisation of the male abuse of power than Angelo’s attempts to compromise Isabella in Measure for Measure, by demanding sex in return for her brother’s life? And what line more resonates today than her plea to us the audience “To whom should I complain?”

Without the First Folio we would neither be able to articulate the bleakest nihilistic despair with Macbeth’s image of life as “but a walking shadow, a poor player, / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, / And then is heard no more”; nor express with more passionate exuberance the exhilaration of being in love, as in Celia’s cry in As You Like It, “O wonderful, wonderful, and most wonderful wonderful, and yet again wonderful, and after that out of all whooping!”

We would have none of the plays quoted above today without the First Folio. So let us attend to the appeal of those two heroic friends of Shakespeare and “Read him therefore; and again, and again.”

*

[1] A ball of thread: quite a good image for the shape of the Globe.

[2] “A Sonnet upon the Pitiful Burning of the Globe Playhouse”

[3] Authors’ transcripts

[4] The first person we know to do so was Edward Dering, on a trip up from his home in Kent. He kept meticulous accounts of his expenses. He spent 6d to “see the elephant”, gave 8d to the town crier for “crying my lost dogs in Fleet Street”, a shilling for a box of marmalade and bought two folios for a pound each. The only item which cost Dering more that trip was a beaver hat which cost him £2 6s.

[5] Note: Thirty-six plays were published in the First Folio (Pericles wasn”t included until the Third Folio), but it seems that at least two plays that Shakespeare wrote slipped through Heminges’ and Condell’s net, and have been lost: Love’s Labour’s Won (which might well in my view be an alternative title to Much Ado About Nothing) and Cardenio (based on an episode in Don Quixote). The tally of plays attributed in whole or in part to Shakespeare is now growing, and could include Edward III, a Thomas More play which is kept at the British Library (part of which is in Shakespeare’sown handwriting) and even Arden of Faversham. When you consider that close to three thousand plays were produced by the professional theatre from the English Reformation to the English Revolution, and two-thirds of them have been completely lost, for Heminges and Condell to lose two out of around forty is not bad going.

__________________________

From Folio’s limited edition of The Complete Plays of William Shakespeare, celebrating the 400th anniversary of the First Folio, features fabulous artwork by Neil Packer, a foreword by Dame Judi Dench and an introduction by Gregory Doran.

More information about the making of this edition is available here.

Gregory Doran

Gregory Doran is Artistic Director Emeritus of the Royal Shakespeare Company. He has been described as ‘one of the supreme Shakespeare directors of our era’ (The Financial Times), and ‘one of the finest present day directors of Shakespeare’ (The Sunday Telegraph). He joined the Royal Shakespeare Company as an actor in 1987, and became its Artistic Director in 2012, programming his first season from September 2013. Greg was awarded the Sam Wanamaker Prize for pioneering work in Shakespearean Theatre in 2012, in 2023 was the recipient of the prestigious Pragnell Shakespeare Prize, is an honorary associate of the British Shakespeare Association, an honorary senior research fellow of the Shakespeare Institute, and a trustee of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.