On Safiya Sinclair, Noreen Masud and Exposing the Sins of Our Fathers

Lily Dunn on the Aftermath of Writing a Memoir About Fathers

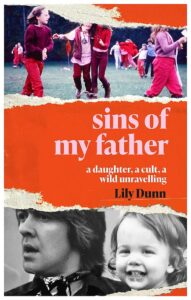

Last year I published a memoir, Sins of my Father: A Daughter, a Cult, a Wild Unravelling, which had been a lifetime in the making. I wanted to capture the complexity of loving a damaged man, and the bind of both revering him as my father, but also pitying him. Initially, this was a private task, much of which I worked out through the intimate process of writing, just me and words on the page. But then the book was published. How would it be received by strangers, and how could I forgive myself for exposing the sins of my father, of writing my version of events and putting them out in the world for all to read?

From the moment we are born, we are taught to respect and revere our fathers, both literarily, and symbolically through the umbrella of patriarchy. As women and daughters we feel this profoundly. Patriarchy, as Adrienne Rich defines it, is, ‘… the power of the fathers: a familial-social, ideological, political system in which men… determine what part women shall or shall not play.’ I had been subjugated by my father. He was a white male of the worst kind, charismatic, entitled, damaged, absent. The symbol of the father is forever present in a culture that is led by men, and my father ruled in my heart and mind despite barely being there for me. I was programmed to adore him, made more pressing in my longing for a man who was distracted by his own need: as a narcissist he fed off validation, surrounding himself with women who reinforced his grandiose view of himself. It went against the grain for me to call him to account for his betrayal of our family, and the fundamental contract of parenthood – to protect his young daughter from his predatory friend when she asked for help. Writing privately, exploring your complex feelings about your father, is one thing, but publishing those words for all to see if another thing entirely.

Even in my final draft I was struggling with the ethical questions that surround memoir: the version that was bought by my publisher was called Starman. But she pulled me up on this title and the fact that I was still placing my father on a pedestal, and I knew I had to be more courageous. During production, when I first set eyes on the hardback: a photo of me as a toddler on my father’s arm beneath this new searing title, a feeling of shame crept in. Here I had written my version of my father’s life and put it out there for all to read and judge and he wasn’t alive to defend himself.

I have since realised that the real power of memoir is that through the process of writing, the writer learns to own their story, and to find authority in its telling. It is a chance to speak, which feels particularly pertinent for those of us who have felt silenced. I was recently deeply moved by two memoirs, both by writers who like me were subjugated by their fathers, How to Say Babylon, by Safyia Sinclair, and A Flat Place, by Noreen Masud. Both explore the cult of the father, in its desperate insecurity to remain in rule, to draw in its family members as disciples to further establish that rule, and the impact this has on a daughter growing up – how it is a kind of identity vandalism: growing up becomes not simply finding voice, but a voice that has been subsumed in another, an older male, complicated, manipulative, self-serving.

Sinclair writes of growing up in Jamaica in the shadow of a father who was a believer in Rastafari, and took its views to a misogynistic and controlling extreme; and Masud is under the rule of a controlling Pakistani father, who considered himself a genius and was suspicious of neighbours, his children’s friends, anyone who came close. I am struck when I read Sinclair’s words at how closely her identity is bound up in his: the family as cult: ‘We can never be a family unit if everybody don’t have the same vision’ says her father like a mantra. ‘All I and I need is one another.’ Masud’s dad is a maverick, ‘doing what he thought best and never asking for permission, in the way that men are allowed to do all over the world. Anyone who disagreed with him, he thought, was stupid and ignorant.’

My dad was not a patriarchal figure, like Sinclair’s and Masud’s, but he did hide behind his disdain for others. Like many of the wandering tribe of the 1970s, he fled to India to join the disciples of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (now known as Osho) because he believed himself to be special and above the laws that bound ‘little lives’. He brought into the fantasy of the ‘New Man’ – a man who is ‘awake’ to an authentic existence, not sleepwalking through the limitations of convention, of marriage, mortgage, fatherhood. The ‘sannyasins’, as they were called, looked down on us regular citizens as uninspired, unfeeling, unenlightened. Sinclair’s father similarly and conveniently attributes anything bad that happens in the world to ‘Babylon’, the personification of western corruption. If someone confronts him, they are a rebel, a jezebel – far easier to see them as contaminated by ‘the Other’ than to face any fault in himself.

But how can one’s personal truth ever be fact?

Despite their differences, our fathers share the toxic combination of male entitlement with fragility – a dangerous narcissism, because to be challenged is to feel the edifice they surround themselves with, so carefully constructed, begin to crack. Masud’s father cuts off contact from her when she is 16, and Safyia’s father’s frustration bursts out in violence; when I challenged my father, he threatened to never see me again. As children we could not understand this was a desperate grasping for power, because their sense of self was as brittle as eggshell. It was a relationship dynamic we had been born into; that many other daughters around the world are also born into. We believed our fathers; we drank the ‘cool aid’ they poured into our glass; until we were no longer able to.

I revisit a diary that I wrote on my return from California, a week of nightmares trying to get my dad into rehab when he had tripped freefall into a desperate destructive alcoholism. ‘The lucid early morning fragility, vulnerability, determination is slowly stripped away with the hours, until the afternoon, when drunk, blank, stupid, he calls the cat ‘Lily’ and sucks on spaghetti. It feels weird to be saying this about him, the lack of respect – if he died tomorrow, it would be painful to see these words.’ I recognise my loyalty, my guilt at having bad thoughts about a man I had been born to respect; the God, an archetype of authority, Dad as king.

Masud similarly captures the challenge of calling to account a charismatic father, ‘If it came to a trial… his students would step up to say what a good man he was. His mother and father, his sister and brother, would all testify to his character. And on the witness stand of the opposition, there would be only me, shaking and tongue tied. I know what I know, I would whisper…’

But how can one’s personal truth ever be fact?

Just before my book was published something remarkable happened: a series of testimonies of sexual abuse by women of my generation who had grown up in Osho’s cult came flooding out on Facebook. My father had not been one of the abusers of children, but there were stories of his mistreatment of women, of his outlandish lying and manipulation to get his way. I felt validated: His betrayal of us was not an isolated case, and maybe I was not wrong to call him out on his crimes. ‘If it came to a trial…’ I would have others standing at my side. Perhaps I was even wise … and lucky. I was one of the first to speak – I wrote a memoir about being the daughter of a damaged and damaging man – and maybe my speaking allows others to also find their voice.

__________________________________

Lily Dunn’s memoir, Sins of my Father: A Daughter, a Cult, a Wild Unravelling, is available from Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Lily Dunn

Lily Dunn's debut nonfiction, Sins of My Father: A Daughter, A Cult, A Wild Unravelling is a memoir about her enduring love for a delinquent father. It will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in March 2022. Her first novel, Shadowing the Sun, was published by Portobello Books. You can find her personal essays in Granta, Hinterland, MIR Online, The Real Story and Litro, and she is a regular writer for Aeon. She teaches creative writing at Bath Spa University and co-runs London Lit Lab.