On Robert Indiana’s LOVE-Hate Relationship with the Sculpture That Made Him a Star

Bob Keyes Considers the Financial Realities of an Iconic Work of Art

When Robert Indiana left New York for good, in 1978, he was a bitter man. LOVE made him an international art star, but he felt he had little to show for it relative to his peers.

Pre-LOVE, Indiana worked in orbs and herms, using painted circles and shapes that resembled ginkgo leaves. His herms were totemlike constructions, made with wooden beams, iron wheels, and other industrial elements that he found in his neighborhood. His personal geography began showing up in his art as early as 1959, when he started working on The Slips, an eight-foot-tall oil-on-board painting naming the various slips of his neighborhood—Coenties, Catharine, Market, and five others.

Politics crept into his work with the election of JFK, and he painted about racial injustice in 1962 with The Rebecca, a political and historical painting about a slave ship that sailed into New York Harbor. On the outer circle, he painted the words “THE AMERICAN SLAVE COMPANY” in stenciled lettering. On an inner circle, he painted “PORT OF NEW YORK,” and in the middle the numeral 8, a reference to the month of August, the month the Rebecca stopped sailing and the month his mother was born and died.

Indiana began riffing on the idea of LOVE in 1961 as a two-dimensional painting entitled 4-Star Love. Painting on a canvas of blood-red paint roughly twelve inches square, Indiana placed the word LOVE in block letters along the bottom edge, with an upright letter O. Above the letters, he arranged four stars, two over two.

From that early idiom, the image evolved until it became its iconic self. Instead of four stars, two over two, Indiana placed the four letters of LOVE two over two. Just as he honored his mother with EAT—a massive, twenty-four-foot-square electric sculpture first shown at the World’s Fair in Queens in 1964—he honored his father with LOVE by framing the letters in the colors of the logo for Phillips 66, where his father worked pumping gas. Finally, the touch of brilliance: he tilted the letter O to the right just so, “as if the foot of the L has given it a kick,” the critic Grace Glueck wrote years later in the New York Times. Indiana also drew inspiration from the Christian Scientist church where he attended services and went to Sunday school as a boy. He never forgot how the otherwise austere church had a single inscription imprinted on the interior walls, which he stared hard at: GOD IS LOVE.

He told people LOVE was supposed to be FUCK with a priapic “U” tilting to the right, but Ellsworth Kelly talked him out of it. For Indiana, the actual word was less interesting than the shape and placement of the letters and the colors.

When the Museum of Modern Art commissioned a Christmas card from Indiana, in 1965, he sent them LOVE. Then the U.S. Postal Service turned LOVE into a postage stamp on Valentine’s Day 1973, issuing 330 million 8-cent stamps and paying Indiana a flat fee of $1,000.

Years before he became the director of the Farnsworth Museum in Maine, Christopher Crosman was working in the education department at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo when the stamps were issued, and Indiana happened to be jurying an exhibition at the museum at the time. The use of his art as a postage stamp unquestionably bothered Indiana, Crosman recalls. “He didn’t complain to me or anyone else, except to say he thought that the U.S. government’s action to ‘cancel Love’ several hundred million times was about right.” Indiana was upset about the Vietnam War and the country’s continuing struggle with the civil and the feminist movements, and he was deeply suspicious of government infringement on individual liberties. And yet he approved the use of the image and accepted the fee.

As early as 1971, he complained that the image was “the century’s most plagiarized work of art.” That was just the beginning.

Indiana’s biographer, Susan Ryan, says his real trouble with LOVE stemmed from his ethical conviction that art could not and should not be copyrighted or trademarked. When the Stable Gallery, in New York, used Indiana’s LOVE as the poster for an exhibition in 1966—the first time the motif was put on public view, following its use as the museum Christmas card—no one involved knew the law or bothered to investigate. They talked about it, but Indiana argued against affixing the copyright notice to the poster because it created a visual impairment and detracted from the image, Ryan says.

Without a copyright notice on to the poster, LOVE went into the public domain when the poster circulated. From that point and until the Morgan Art Foundation—a for-profit company that purchased the intellectual property rights to LOVE from Indiana, financed some of the artist’s most ambitious projects, and eventually sued him—began claiming it back, LOVE was fair game. According to Ryan, Indiana later applied for a copyright, and was rejected on the grounds that a single word could not be protected. He did not appeal the decision. He was advised to seek a trademark, which he declined to do.

His logic was murky and flawed, but it was rooted in the idea that he did not want his art to become a brand or commercialized. “But that’s exactly what he was doing by not obtaining a copyright,” Ryan says. “All art today is commercial. We all understand that now, but back then, it seemed to make him less of an artist. It seems like the dark ages to think that way now, but that’s the way it was and that’s how he felt.”

Other than the $1,000 Indiana received for the stamp and whatever he earned at the Stable Gallery, he received nothing else for LOVE until three decades later, when he began doing business with Morgan Art.

Indiana resigned himself, and decided the more the image proliferated, the more famous he would become. He did become famous, and also an easy target. As early as 1971, he complained that the image was “the century’s most plagiarized work of art.” That was just the beginning.

In hindsight, it seems tragically fitting that Indiana’s career would eventually be mired in accusations of forgery and fraud. LOVE, which became one of the most recognized images of the twentieth century, was without an “original,” in a fine-art sense: it was seen as a Christmas card, then a poster, then a series of paintings, then a sculpture. Almost from the moment it was introduced, it existed in multiple forms and lent itself to fraudulent LOVE pieces to be mass-produced by anyone who wanted to do it.

Even though he regularly participated in making otherwise fairly straightforward deals more complicated than they needed to be—or explicitly caused the complications—what Indiana imagined to be the dramas of the New York art world took their toll on him. He fled New York City for the island of Vinalhaven off the coast of Maine with a chip on his shoulder and ready for a new beginning, but trouble with fraudulent artwork would follow him wherever he went.

*

Throughout his career, Robert Indiana would pay studio assistants to perform all manner of tasks, including applying paint and underpaint to canvases. Indiana or his intermediaries—such as Simon Salama-Caro, his agent and dealer, and the American Image Art publisher Michael McKenzie—consulted with foundries that produced sculpture and printmakers who made the prints. Early in his career, Indiana was a hands-on printmaker, and a good one. But he had little involvement in the creation of the large-scale, three-dimensional sculptural pieces that came to define his public image. He left it to others to communicate his specifications to the craftspeople who actually made his art. Some he talked to, some he didn’t.

Josh Dow and Lauren Holmgren—recent grads of MASSArt, in Boston, newly married and eager for work—made Indiana’s original HOPE sculpture, a six-by-six-foot, stain-less-steel behemoth that was set on a four-foot base for the Democratic National Convention at Green Foundry, an enclave of creativity in Eliot, Maine. They were finding their way in the art world when McKenzie called one morning early in the summer of 2008.

“He was talking a lot and really quick and he mentioned Robert Indiana, and did I know who Robert Indiana was. And I said, ‘Well, of course,’ because I went to many years of art school,” Dow recalls more than a decade later.

That phone call began a bizarre short-term relationship with McKenzie, but they never met Indiana and barely even spoke with him. “We were allowed to come to his eightieth-birthday party. We saw him come out of the house, but we were kept at arm’s length,” Dow says. “He did call me once. He said, ‘Are you making Michael happy?’ I said, ‘I think so. I hope so.’”

When McKenzie enlisted Dow and Holmgren, they say he could offer no more than a concept of what he wanted produced. Dow asked for a drawing so he could formulate a quote, and McKenzie’s assistant sent something that “looked like it was made on Microsoft Paint,” Dow says incredulously, referring to an early and rudimentary graphics program. “It just had letters, but it wasn’t art. We looked at it and said, ‘What is this?’ It was completely useless.”

But they wanted the job, so they improvised. Dow’s sister held a degree in graphic arts, and they asked her to design the HOPE sculpture based on McKenzie’s crude rendering. “We spent a few nights at her house drawing the HOPE sculpture in vector graphics,” Dow said.

They made two versions and sent both to McKenzie. After McKenzie told them Indiana signed off on one, they prototyped the piece by cutting flat versions of each letter from sheets of plywood and stacking them. When the prototype was approved, Dow enlisted a local company to manufacture the final parts in stainless steel and “called in all the people I knew,” he says, to assemble the piece. Indiana had no hand in its fabrication, never met the artists who made it, or even saw the final piece before it was shipped to the Democratic National Convention.

Dow laughs at the experience today and is without regret. He chalks it up to part of his education in the high-end-art world. McKenzie—not Indiana—paid the foundry, eventually. He won’t say how much, other than that it was a fair rate for a young couple with barely any track record—though far less than they deserved. “It was sort of circuitous and round-about and lumpy, but in the end, everyone got paid,” he says.

As for McKenzie, Dow just smiles. “We haven’t been in touch.”

When asked to confirm or comment on Dow’s version of how things went down with HOPE, McKenzie declined.

_______________________________________________

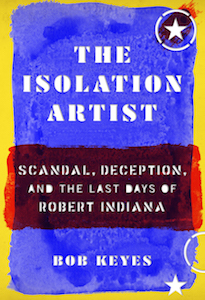

Excerpted from The Isolation Artist: Scandal, Deception, and the Last Days of Robert Indiana by Bob Keyes. Excerpted with the permission of Godine. Copyright © 2021 by Bob Keyes.

Bob Keyes

Bob Keyes is a nationally recognized arts writer and has worked for the Portland Press Herald since 2002. He has received numerous awards for his writing, including the Rabkin Prize for Visual Arts Journalism in recognition of his contributions to the national arts dialogue. He lives with his family in Maine.