On Reckoning with a Mother's Relentless Need to Save Everything

"The tyranny of things. Do we possess them? Do they possess us?"

I’m laid up in bed while my friend Medrie, staying with me as I recover from a hip replacement, reluctantly spoons leftovers (who saves oatmeal?) into a Tupperware. I watch her examine the lid, frown, throw it out. I insist she retrieve it. It’s broken, she explains. I do not correct her. I do not say that “broken” isn’t the right word. It’s torn. There’s an inch-long tear on an otherwise-good five-inch lid. Just give it to me, I say.

I could argue it’s the painkillers. Or the idea of being helpless while my friend controls “my space.” An objective correlative, the psychic reminder of my worn-out hip joint, labral tear. I’m too young for a hip replacement. And what have they done with my old hip, which has always been part of me? But it’s the lid. What, I demand, will I use to cover the container? She pulls it from the trash.

The vehemence with which I attacked my—amused? alarmed?—friend must seem irrational. What could it cost to buy a new one? But they don’t sell lids. And what’s a container without a lid? For accuracy’s sake, it’s not, by definition, a Tupperware. Habit maybe, but I call any food storage receptacle a Tupperware. My mother sold Tupperware.

My mother. On an overnight with my sister, my mother pulls a velvet-wrapped dagger of glass out of her handbag. Her make-up mirror. My sister and I had, on seeing it the year before, bought her a new one. Where was it? What would make someone save such a thing? But I see myself in my mother’s alarming mirror: why get rid of something that still works? Hadn’t I grown up watching my grandfather repair all manner of things—our rusted window-screens stitched together with spiders of black thread? Didn’t everyone glue the handle back onto the paintbrush, wrap it with duct-tape? Stick the head back onto the Infant of Prague with a toothpick? Couldn’t I glue or tape the lid? Sew it?

Why is it so hard to throw things out?

*

Last fall, while my mother was in the hospital, I spent ten days in New Jersey with my father. Every time I reached into the closet for a box of pasta, can of tomatoes, some wedding favor or broken figurine would slip from its tangle of yellow Shoprite bags, releasing a cascade of bills, circulars, birthday cards, Bed Bath & Beyond coupons to the floor. Your mother, my father would say, as I picked up years-old pharmacy enclosures (my mother reads them), clippings—De-germ with Lemon! 25 Uses For Vinegar. How to De-clutter. My father was desperate. He belongs to that tribe—unsentimental, minimalist—who can throw things out. It has been a 62-year struggle. Do something, he said.

Imagine what lurks in every drawer. To list it all would upend this essay.

It looks like a museum! visitors exclaim on entering my mother’s house. Your apartment is so neat! friends tell me. Such order! My mother and I do not appear in need of the extreme “tidying up” that a popular Japanese anti-clutter book recommends. We are tidy. And, though I have to fight my urge to save, part of me—the internal chaos that makes a person crave order— loves to throw things out (or at least contain them). In this way I am both my mother and my father. It’s a dialectic.

Do something. Get rid of it. Don’t tell her.

I start in the garage, essentially a storage room (the car’s kept outside) about the size of my entire apartment, lined with the dressers, chests, credenzas, shelves, cabinets, armoires (did we ever use this word?) from our apartments in Brooklyn, then our house on Staten Island, each crammed with things. Behind one door I find the cards: unused birthday cards, anniversary cards, Christmas, Easter, Valentines, Mother’s Day (who stores mother’s day cards just in case?): To a Son, To a Daughter, For a Niece On Her... Here are give-away blank cards from St. Jude, March of Dimes. Packets and packets of envelopes. My mother could open a gift shop. She’s got boxes of shopping bags, boxes of boxes, embossed napkins, wrapping paper, tissue paper, decorative bows, and rolls and rolls of ribbon. Candles and soaps in their velvet-lined gift boxes. Here, too, address labels, notepads—From the Desk of, To Do! Betty’s List! And more yellow Shoprite bags. Hundreds.

I’ve described one compartment. Imagine what lurks in every drawer. To list it all would upend this essay. Writing is about selecting the significant detail. Tossing the clutter. (Or saving it to another document.)

*

My mother saved my (our?) umbilical cord. This was the turf of her first serious argument with my father’s mother, who, when she found it in a jar in the kitchen cabinet, threw it out. She saved our baby teeth. All four siblings. (Disaster, she phoned once to report, the teeth got all mixed up.) I understand this. Since childhood I have found it hard to throw away a fingernail, my tissue, in a strange place, and used to save such things until I found a familiar garbage pail. I whispered goodbye to my hair when my mother cut it. Even now I’m uneasy when I have to leave it on a salon floor, as I watch the assistant sweep it into a pile of other hair. Primitive to believe that to leave a piece of yourself in harm’s way is to give someone power over you. To put you, or it, in danger. (But remember Rosemary’s Baby?) Magical thinking, the belief that to throw away a gift is to endanger the giver.

As a child I was afraid, not only that I would die before I woke, but that my things, unwatched, were in danger. I pray the Lord my soul to keep. Bless us and keep us. I didn’t want my dolls, shirts, hairbands, my grandfather’s key ring, to be lost or lonely. I said goodbye to my bed when I went to school. The fear it would disappear? I would disappear? My parents? If I should die before I wake. I prayed to protect and preserve everyone I loved. I think I believed I could. I carried that key ring as if it would keep my grandfather safe. When my sister died, I took her coat and scarves. I will never dry clean them. I keep her tissue in the pocket. Now I have her teeth. Our teeth. We’ve had them so long. How can I throw them out? I call my sister’s daughter to see if she’ll take them.

*

The garage is overwhelming. I move to my mother’s walk-in closet: racks stuffed with suits and skirts she wore to work in the 70s. Maternity clothes she made herself. Dresses she dieted herself into for weddings decades past. Jeans, trousers, blouses, t-shirts, robes, belts, hats, coats, handbags. All but a three-foot section are clothes she’ll never wear again. After wedging back several print maxi skirts, I sink to the floor. Here, in a box under other boxes and bags and stacks of storage bins (one containing a dozen Lancôme sample cases with their lipsticks and blushes) is where I find the teeth. I find decades of letters and cards, many from myself, pages and pages written to explain myself to my mother, to separate, distinguish myself from her.

In a corner of the closet, in a drawer of a 1950s end table, I find the clothbound blank book I gave her. Keep your secrets in here, I’d written on the flyleaf. 1983. It’s empty. Not a word. But it is as if she has written a giant FUCK YOU! on every page. I’d wanted to give her a place to keep the kinds of reflections that could have helped her. Haven’t they helped me, the journals I’ve kept since I was 14? Hundreds, stacked in my closet, the records of dreams, obsessions, confessions, events recorded before they became memories. Part of me feels a thing hasn’t happened until I’ve written it down.

How can you die when you still have all these clothes?

It occurs to me now that perhaps my mother’s closet is her journal. A record of who she was, where and when she worked, married, gave birth; of what she wore, when, one by one, her kids moved out. Her closet an elastic sentence, its branching syntax expanding to contain her history of baptisms, communions, dinner dances, graduations. To enter it is as much a violation as if I were to read her diary. It would take empathy to imagine what all these clothes mean to her. Would my mother value my many notebooks, each with its record of study, of poem drafts, its lists of books read, movies seen, museums visited, concerts, plays, etymologies, definitions, recipes, quotations?

What would she make of the commonplace books, the folders and binders, the organized clippings (25 Uses for Lemons, De-clutter Now!), the meticulous medical notebooks I’ve kept for friends, for my sister. My sister is dead. My friends have died. I’ve saved no one. Why can’t I throw the notebooks out? What will happen to them when I die? Perhaps I keep it all as a hedge against ending. How can you end a list? The thing about lists: they continue. How can you die when you still have all these clothes?

*

When I read that Japanese get-rid-of-stuff book, I thought of my father, who, time and again while I was growing up, moved through our basement on Staten Island in a frustrated fit of throwing out, tossing armfuls of junk into trash barrels while I followed behind, pulling them from the garbage: our drawings, finger paintings, “meteorites,” to hide them. Decades later, helping my parents move to the house they live in now, I would find them behind my father’s workbench. The tyranny of things. Do we possess them? Do they possess us? I begin to see why we say a person is “possessed.”

But even my father wouldn’t throw out the box of ornaments my siblings and I made in grade school. They’re safe in the crawlspace (beautiful word): the Santa my sister fashioned out of a toilet paper roll, cotton and crayon. We couldn’t save my sister, but we can save her Santa. And my brother’s wreath—cardboard, cotton balls, tin foil, sparkles—where will it go? I can’t explain what I feel about such things, which meant nothing to me then. Does everything, in time, become a madeleine? Does object plus time equal feeling? I’m reminded of the “Time Passes” passage in To the Lighthouse when a shawl Mrs. Ramsay casually wrapped about a skull one night is transformed, years later, into the shawl—a chilling emblem that haunts the reader.

Why isn’t it enough to remember? The brain is wider than the sky, Dickinson says, for one the other will contain. But it’s not enough to hold the past in my head. I want the cotton ball wreath that brings it back. No wonder my favorite part of school trips was the souvenir shop.

Perhaps my mother felt that her broken mirror held, actually held, the years and years of her reflections. And when memory goes? Every object has its correlative. Without it, it’s just junk.

But how to explain the Tupperware lid?

*

I love everything, my mother said last week. It was Memorial Day. We were discussing the possibility of an independent living apartment, another move, one that would require drastic downsizing. I suggested what it might be like—imagine!—to live in a place in which everywhere you turned you saw something you loved. You saved it because you love it! I love everything, she said. I understand. I tell her we’ll give it all—the Hummels and silverware, the dishes, couches, chairs, the angel figurines and apron I bought her in first grade—to my niece (who still hasn’t answered me about the teeth.)

The principle of that Japanese book is to get rid of anything that does not bring you joy. But why is joy the guiding principle? Why not save the thing that rips your heart open? Why not save what reminds us of our greatest experiences of interiority and solitude, anguish, dread, no matter how painful. Oh God, why not save everything?

*

Because I live in a studio, one room is every room, and, sitting at my kitchen table I am beside the dresser I’ve had since I was three. I know which drawers were mine, which belonged to each of my siblings. This chest has moved with me through five apartments over forty years. It has been painted white, turquoise, eggshell. It has been clawed and bitten by three pairs of cats. It’s ugly, my friend Daniel says. But he can’t see that what he would call its “element of greatness” comes from its history. My history. It is not a great piece. I don’t even know that it could be called a “piece.” Whether it has a style. Utilitarian? But I remember staring up at the blond wood-grain patterns, which I can still see although my mother “antiqued” it with steel wool, hammer and paint when I was twelve. Where did they buy it? Some unpainted furniture place? Did they varnish it? If I stripped it now, down through the layers of paint and antiquing, what would I find? The product of some anonymous factory?

But I look at it and see how, one Christmas Eve, I tied my sister, brother and myself, in our rocking chairs, onto its knobs with jump rope to pretend we were reindeer. How rocking and prancing we pulled it down on stop of us, then screamed as our ceramic Dalmatian from Coney Island shattered, our fire hydrant bank crashed, pennies rolled across the floor, and our mother raced in from the living room. Why am I writing this? Sentence by sentence I’m back. My sister is alive, my mother young and six months pregnant. I have arrived at what Bachelard calls “the land of Motionless Childhood.”

I cannot throw this dresser out. Perhaps, I say to Daniel, I can be buried in it. It’s not a preposterous idea. It would be the ultimate repurposing. And that, perhaps, is what writing is. The first time I had a physical impulse to write a poem (though I wouldn’t have called it a poem) I was nine. We were visiting my grandparents in Brooklyn, the first time back to our old building—the clotheslines and courtyard and vestibule—after having moved to Staten Island. Nostalgia? I don’t think so. I ached to have it. To keep it. To capture something by trying to put it in words: change, loss, the sense of time passing, how utterly awful and inexpressible it felt. Our familiar home was now past and burnished with the glow of this fact. I could try to make something to contain it, the way this jumble of notes, thoughts, memories might become an essay. Is memoir etymologically connected to armoire? I make a note to look it up.

*

I’ve been trying to find a grand unified theory to encompass all the reasons we—my mother and I—hang onto stuff: it still works, I might need it, x gave it to me, it reminds me of, I can use it as a _____, it’s part of me, I just can’t. Sometimes they bleed into one another. When, years ago, I handed a tangle of gold chains, crucifixes, and religious medals to my dentist so he might melt them into a crown (I’m a dentist, not a jeweler) it was partly because I was broke, and because they’d been gifts, and I loved the idea of resurrecting them, carrying the old holiness in my mouth. Primitive, yes, and a practical bit of recycling.

Perhaps it begins with a helpless dread in the face of flux, the inevitable change and loss, that awful impermanence Buddhists urge us to accept. My mother, child of the Depression, whose own mother died when she was 13, does save just about everything. What I do is different. I organize. Like a scientist, I categorize and archive and preserve. For this reason I love things that contain other things. Boxes, drawers, notebooks, closets, Tupperware, vials, jars, journals, shelves, bags, folders, binders with “durable” sleeve inserts, handbags with their many zippered pockets. I love the idea of a Container Store. I love words that contain the histories of other words. You’ll have noticed that I love parentheses—those little bookends that contain the interruptions, flights of imagination and association I want to save. I love sentences whose syntax expands to contain more and more of what we accumulate. Perhaps, in my yearning for permanence, I want this essay to contain my childhood. It was not an easy childhood; why so fiercely hang onto it?

*

That Memorial Day in my parent’s kitchen, unable to find a matching top and lid in three drawers of Tupperware, I gathered every container, many of which had been separated from their lids by inches or years, and dumped them on the floor. My mother watched as I tossed whatever was without a lid (or bottom), even if in perfect condition, into the recycling barrel. (I saved a few, just in case.) I even found a lid that was the size of my torn lid. Since I knew my mother would go through the recycling when I left, I took it all home with me on the bus.

The frenzy I felt in the process, the feeling of relief, of calm, I had when all the lids were matched and back with their partners, helped me understand something. The act of organizing calms me. And all the saving—it’s anxiety. Every reason I save things goes back to anxiety. This I share with my mother. And its source? We are going to die. We are going to forget. We are going to lose what we most love. And I understand why, as my mother’s memory begins to fail, I get irrationally annoyed if she can’t remember a high school friend whose mother stole a trench coat from Korvettes. She has been not only the container of my history, but was also, in fact, my original container. And I cannot bear to let it go.

__________________________________

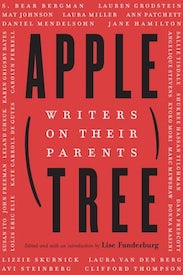

Excerpted from the forthcoming Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents, an anthology of essays to be published by the University of Nebraska Press in September 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Donna Masini.

Donna Masini

Donna Masini is the author of three books of poems—4:30 Movie, Turning to Fiction, That Kind of Danger—and a novel, About Yvonne. Her work has appeared in journals and anthologies including Poetry, Ploughshares, APR, Paris Review, Pushcart Prize, Best American Poetry 2015. A recipient of grants from the NEA and NYFA, she teaches in the MFA Creative Writing program at Hunter College. (edited)