On Photographing a Generation of Gloucester Fishermen

Nubar Alexanian Documents the Dying Art of East Coast Fishing

The following photographs are excerpted from Nubar Alexanian‘s Gloucester: When the Fish Came First.

*

Rachel Cobb: How did you fall into documenting these fishermen?

Nubar Alexanian: I moved to Gloucester from Boston in 1971. I was teaching photography and having shows, and that was getting a little boring. I wanted to start doing magazine work and learn how to do photo essays, so I decided to find the most successful fishing family, at least in Gloucester, if not on the East coast, and follow them. That turned out to be the Brancaleone family. They had two boats. They were the boats that everyone else wanted to know where they were fishing. I followed them for about a year and a half and went on four ten-day trips to Georgia’s Bank.

Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1980

Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1980

Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1978

Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1978

I have a middle ear balance problem and get seasick very easily. After the first trip, when my wife came to pick me up, I had lost 20 pounds. She just drove right by me. Every time I would tell the Brancaleone family I needed to go again, they were just incredulous. It was painful for them to see me so seasick. So they were like… No! But they always agreed. When I sold the story to Geo, the magazine asked me to go on one more trip—a winter trip (which are really bad). But when you’re working on something and it has you, you just have to keep up with it.

Joseph & Lucia II, Boston Fish Pier, 1980

Joseph & Lucia II, Boston Fish Pier, 1980

RC: What years did you work on this project?

NA: I worked on offshore fishing from 1978 to 1981 when fishing was at its peak and when it started its decline. The Brancaleone family sold both their boats soon after this because they saw what was happening. But I still shoot here all the time. Even now I shoot everyday just because of the kind of place it is.

Breakfast, Joseph & Lucia II, 1980

Breakfast, Joseph & Lucia II, 1980

RC: In the book’s introduction, you describe your work as a “historical document describing a way of life that will never ‘be’ again.” How are fishermen working differently now?

NA: This book describes a way of life that will never be again which is that someone could come from a place like Italy, catch some fish, buy a larger boat, maybe buy a second boat for his son, and make a good living. That is gone and will never return, not in my lifetime. Back then, there were 300 boats in the harbor. Now there are maybe two dozen. All of the fishermen hanging out, the pride of having had the best week out on the water, bringing in the most fish—all of that is gone.

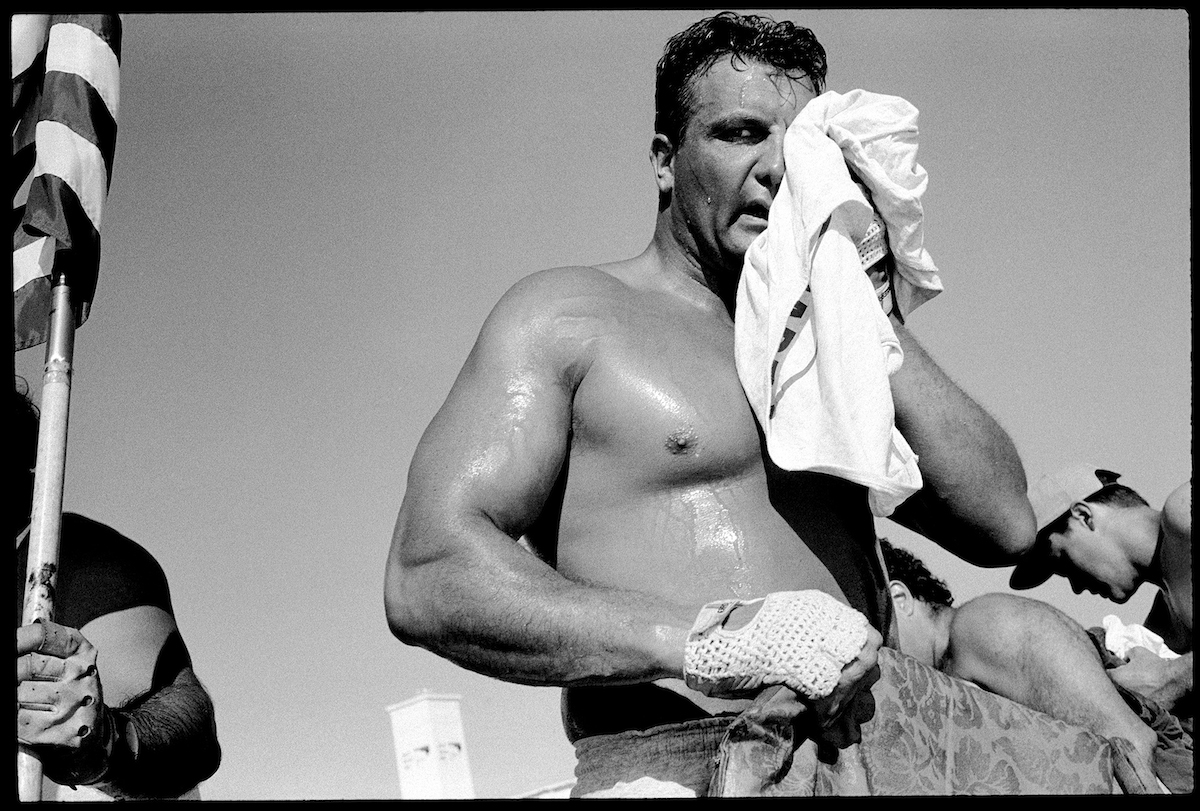

Seine Boat Racer, Pavillion Beach, 1997

Seine Boat Racer, Pavillion Beach, 1997

Sunday Procession, St. Peter’s Fiesta, 1997

Sunday Procession, St. Peter’s Fiesta, 1997

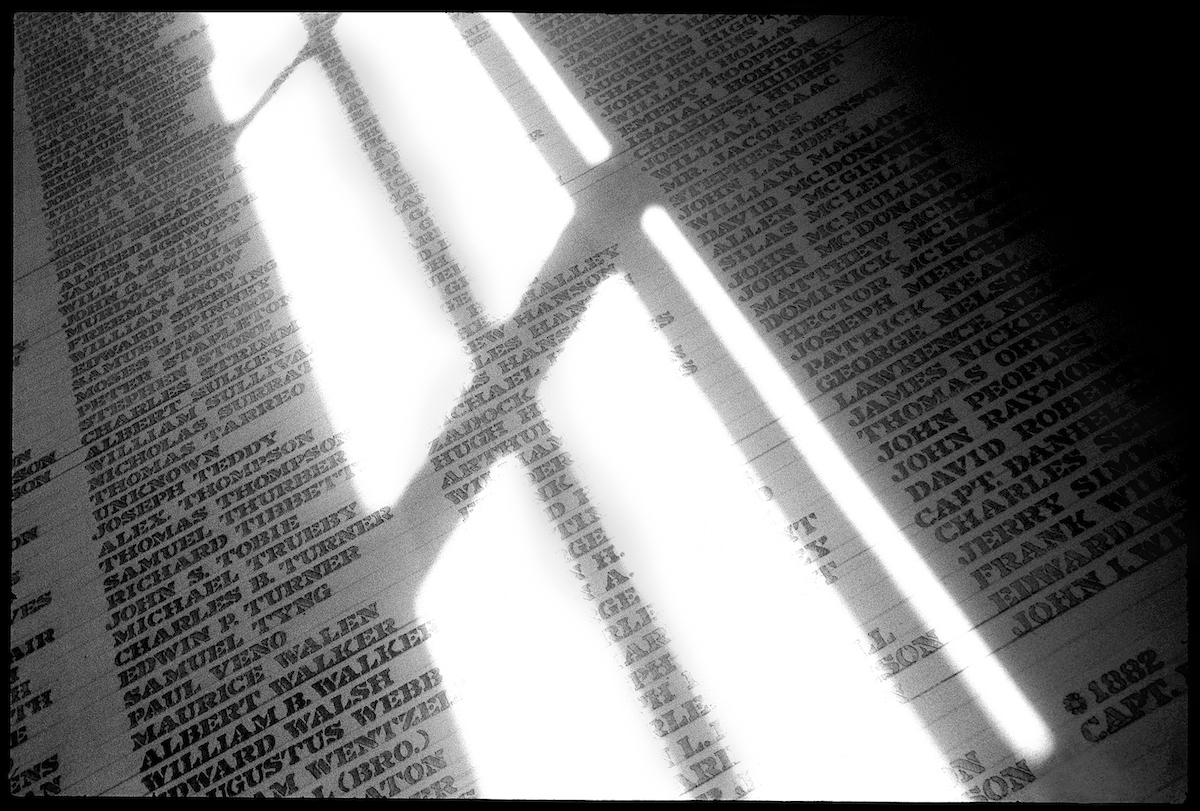

Fishermen Lost at Sea, City Hall, 1999

Fishermen Lost at Sea, City Hall, 1999

RC: What else has changed that you documented?

NA: The Haddock on Deck (1), that image. When the boats reach the fishing grounds and set out their nets, they drag their nets for about three hours, or until they feel full. Then they haul back, unload the catch and go right back out. They do that for twenty-four hours a day, for about ten days, until they have enough fish to sell. So this is one tow. It’s about ten or fifteen thousand pounds of Haddock on deck. You won’t see that many fish on deck at one time any more.

(1) Joseph & Lucia II, Haddock on Deck, 1980

(1) Joseph & Lucia II, Haddock on Deck, 1980

Icing Tuna, Cape Ann Tuna, 1998

Icing Tuna, Cape Ann Tuna, 1998

RC: When you began the project at fishing’s peak, did you sense it coming to an end?

NA: No, I did not see the decline coming. It was only a few decades later, looking at these images, that I saw this is actually a historical document because we will never see this again. It really was strange to me that the Brancaleones got out of the business right away. I think it sent a message to everybody that they saw something a lot of people didn’t see. Back in 1979, 1980, the equipment they used was different, less sophisticated. Today they have really high tech equipment that can locate a school of fish and scoop it up. The guys I fished with were very intuitive. They were good fishermen because they knew the water; they knew the time of year. They kept really good diaries and charts. They had an instinct for it. I’m not saying other fishermen didn’t. But as technology increased, you didn’t need instinct. All you needed was a satellite image, a bunch of maps, high-tech sonar and you’d be good.

Hauling Back Nets, Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1980

Hauling Back Nets, Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank, 1980

RC: Your image of Ten Pound Island (2) took several attempts to make. Why was that important to you to keep going back?

NA: At the heart of everything I do are my own personal projects. I went to Peru in 1974 on a gig for Harvard University, and I kept going back there over 15 years to be able to see in my pictures why I loved that country. Gloucester was like that for me. If I’m on a magazine assignment for a couple weeks, I have to get everything I need in two weeks. But here I can go back to the same place over and over again. If I have a feeling there’s an image there, I’ll keep shooting it. Ten Pound Island was like that. I think I shot it seven times. I had to make a 45-minute boat ride from where my boat is moored over to the harbor. I would get out and stand in the water with a panoramic camera attached to a tripod and shoot it. I didn’t know what wasn’t working until I thought I’m going to line up the high water mark on the big boulder with the city and see what it looks like. But even then, it’s just an idea. It has to work as a photograph. I love one of the things Garry Winogrand used to say, “I take pictures because I want to see what something looks like photographed.” This is so true! It ended up working really well, and obviously the birds cooperated. You get lucky, but sometimes you earn your luck.

(2) Ten Pound Island, Gloucester Harbor, 1999

(2) Ten Pound Island, Gloucester Harbor, 1999

RC: Are there other images that took you several attempts to make?

NA: This image on Walker Creek (3), the ice floes. This is a creek made up of brackish water. In the winter, as the tides change, the water comes in, freezes and then it goes out and it breaks up. So there are these huge pieces of ice cracking this canoe that was left in the marsh. It just looked great. And I kept saying to myself, this looks easy, almost too easy. I photographed it probably a dozen times in a week. All of the photographs in this book, except for three, are shot on film. I had to shoot and develop the film, make the contact sheets, look at them and then go back and keep shooting. It wasn’t until the fog rolled in that the photograph became a gate to nowhere. Suddenly it became this mysterious picture that describes why I love living here, why I love shooting here.

(3) Ice Floes, Walker Creek, 2000

(3) Ice Floes, Walker Creek, 2000

The interesting thing for me about shooting in a place like Gloucester is, since it’s an island, the light bounces off the water into the landscape, and it’s the most beautiful light. There’s beauty everywhere. It’s really easy to take a beautiful picture of something that’s already beautiful. But that’s not simply what we do as photographers. We have to go out and make interesting pictures of the mundane things of life. And that’s much more difficult, much more challenging, and much more interesting to me.

St. Ann’s Church, 1999

St. Ann’s Church, 1999

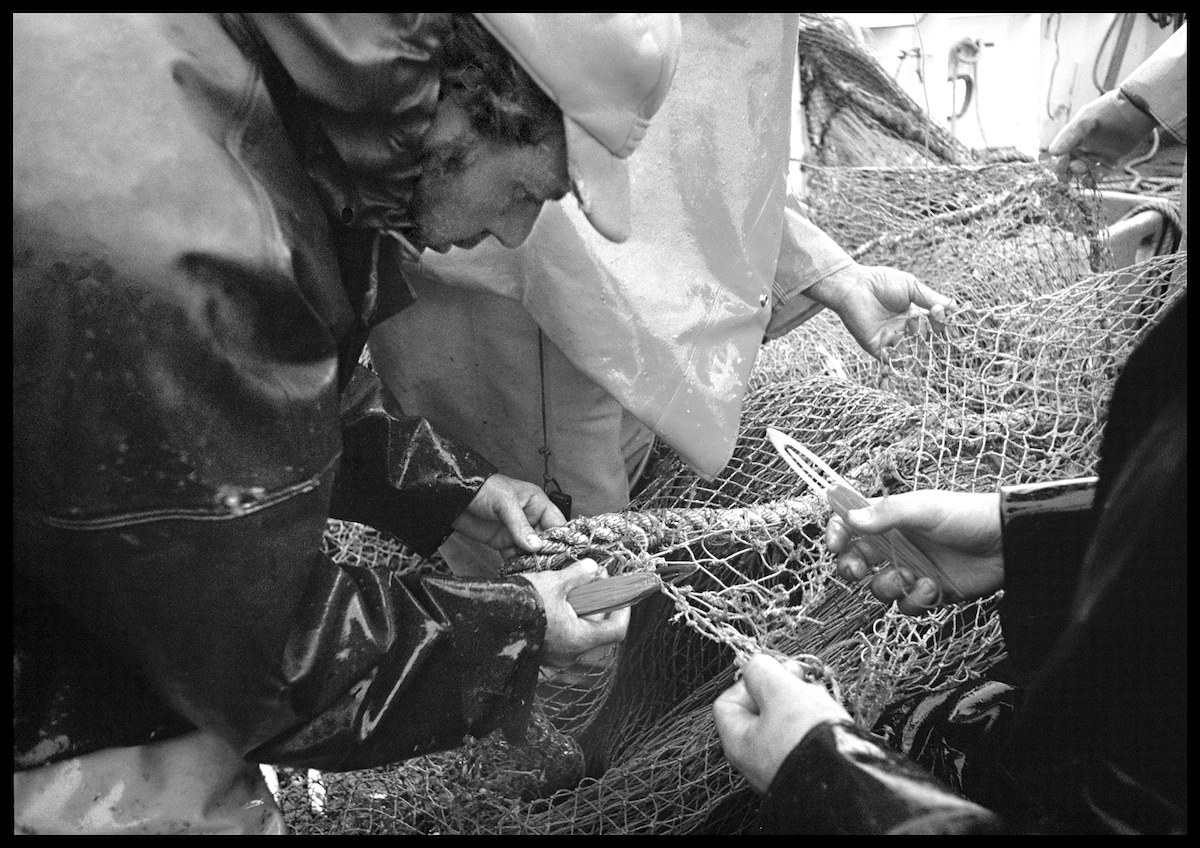

Mending Net, Joseph & Lucia II, 1978

Mending Net, Joseph & Lucia II, 1978

Fishermen are treated romantically in writing and painting. The thing I didn’t want was to produce a set of romantic images. Some of them are—it’s hard to stay away from that—but they are more interesting than romantic. If you look at some of the pictures of them at night, you lose any sense of where you are. They’re so focused on the fish. These guys work so hard, harder than anyone I’ve ever seen. It is supposed to be the most dangerous job in the world. It’s extremely disorienting, which is more interesting to me than simply being romantic.

Winter Storm, Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank,1980

Winter Storm, Joseph & Lucia II, Georges Bank,1980

RC: Do you read books that inform your work?

NA: I deliberately don’t research what I’m going to shoot unless it’s an assignment. The work I do for myself, I like to just wander and walk. I’m the kind of photographer that likes to wait. I used to carry small poetry books in my camera bag and I just read and waited to see if something would happen. We have to shoot through what we know to find something that’s unique. My pictures don’t have to be about what’s in front of the camera to be true about what I’m seeing.

Essex River, Conomo Point, 2013

Essex River, Conomo Point, 2013

RC: I understand you do not crop your images. Why?

NA: The kind of photographs I’m interested in are images that can stand on their own, without context. No captions, nothing—just an image. I have worked really hard over my career to find my own “ voice” in the medium, something that belongs to me. Within that visual vocabulary, I don’t crop my pictures, I don’t ask people to do anything in front of my camera unless it’s something obvious, like a portrait. The photographs that are most compelling to me are about three things: they are about the subject, they are about the photographer, and they are about photography. And juggling those three balls is thrilling. For example, a newspaper photographer’s pictures, by necessity, have to be more about the subjects than about the photographer. That’s their job. But there are different kinds of documentary photographers and photographs. To me, photographs are not inherently very good at narrative, at storytelling. There are exceptions to that, for sure. But for the most part I think it’s true because you don’t really know what a photograph is about unless there’s help, like a picture that comes before and after it, or a caption. I’m interested in image as metaphor. Photographers are better at being poetic than they are at being narrative. Those are the pictures I like making. Those are the pictures I like looking at. And this book is a combination of the two.

Fishing For Striped Bass, Essex River, 2013

Fishing For Striped Bass, Essex River, 2013

RC: The image of the fish arranged neatly on the sand looks different from the other images in the book. The other photographs feel like you have been an observer who has not influenced the situation. Tell me about this image.

NA: These are called menhaden (4). They are small bait fish and they are beautiful. They look like silver dollars swimming in the water. I wanted to photograph them, so I brought some home along with a bucket of sand. But I didn’t have any idea how to set it up. So I asked my twelve-year-old daughter to do it. She charged me five dollars. She patted the sand down and lined them up like that, and they looked like a school of fish. I would never have been able to do that. I don’t think there is another photograph in this book or anything that I’ve done ever that was styled like that. It’s a fun image to look at.

(4) Menhaden, 2000

(4) Menhaden, 2000

RC: Your book celebrates a way of life that is no more, but the same could be said of this project itself. The fact that you worked for 40 years to bring it out shows a perseverance and craftsmanship rare these days.

NA: That’s a good point. I came up in a time in the early 80s and 90s as a documentary photographer, a magazine photographer. It was great. Everyone I knew was working on interesting long-term stories. Editors in New York were fantastic. I was doing a book called Where Music Comes From, and I gave editors who hired me regularly the names of musicians who I wanted to photograph. Many of them assigned me to shoot those musicians. For myself and other photographers I know, long-term projects are at the heart of what we do. Even magazine work is something that, in some cases, takes us away from projects we’re working on.

I don’t really see this as a 40-year project so much as a lifetime of work. It will continue until I’m not around anymore. I just shoot all the time, and much of the time I don’t really know what I’m doing. This is really important in the process of doing photography—and probably in other visual arts as well. If you know what you’re doing, you are in a place you’ve already been.

Tern, Essex River, 1999

Tern, Essex River, 1999

Rachel Cobb

Rachel Cobb is a photographer who lives in New York City. She has worked for numerous publications including The New York Times, Time magazine and Rolling Stone magazine. Her award-winning book Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence was published by Damiani in 2018. You can find her on the web at @rachelcobbphoto.