On Opera’s Indisputable Rules of Gravity

Matthew Aucoin Considers the Constraints and Liberation of an Art Form

Opera is governed by strict, unwritten, irrational laws. These laws are diabolically hard to predict or pin down, but they enforce themselves implacably, like the edicts of the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland. I think these laws are best articulated as reversals: reversals between what works in life and what works onstage, between communication through speech and through song.

Opera’s first law of gravity: the external is the internal. Opera is a highly extroverted art form—sometimes grotesquely so—but what we perceive as abundant exteriority is always the manifestation of an inner state, whether individual or collective. There is no such thing as objectivity in opera; we are always inside someone’s head, either an individual’s or a crowd’s.

There’s an important distinction here between opera and spoken theater. In plays, as in everyday life, the actors’ lines emerge from silence, and are surrounded by it. In opera, however, the surrounding atmosphere is made not of silence but of music, and music is puppyishly incapable of remaining objective. (Cinema emerges directly from opera in this sense: films’ interstitial spaces are almost always filled with music.) Even the sections of operas during which no one sings—overtures, interludes, etc.—give voice to interior states, even if we are not sure exactly whose. The intermezzo in Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (1890) is the boiling-over of an entire community’s grief and frustration. The overture to Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (1786) captures both the giddy, bubbling energy of the characters’ conflicting desires and the sense that a playful spirit is hovering just overhead, a mischievous Arielor Puck-like presence that makes itself felt, in flashes, through the orchestra.

Total objectivity is surely impossible in other media, too. But opera composers—unlike, say, documentary filmmakers—never had a prayer of creating the illusion of objectivity in the first place. This is both a constraint and a liberation.

*

Opera’s second law of gravity: in opera, all speech is dream speech, whether it wants to be or not. The dreamlike and the surreal are opera’s daily bread, whereas everyday speech acts, like making small talk or ordering takeout, have a strong tendency to go wonky. The more normal a speech act would be in real life, the more likely it is to sound absurd, or unintentionally funny, in opera. A world whose atmosphere is made of music is automatically a dreamworld, and within this world, what is communicated tends to have the unguardedness, the childlike directness, of dream speech. It makes perfect sense, in opera, to lucidly reveal long-buried traumas, to confess to shameful desires, to utter curses, prayers, prophecies, wordless primal cries. If they’re done right, a listener can take all these things very seriously.

In opera, happiness is not only a sad song but also frequently a song of madness or blind, bloodthirsty rage.

An earnest, in-depth debate about health care, on the other hand, would make no sense at all. There is a thriving YouTube subgenre of musicians setting speeches by public figures (often politicians) to music, in some cases simply playing an instrument along with the unfortunate orator’s speech patterns, a note for every syllable, carefully tracing the voice’s implied pitches as it rises and falls. This is usually more than sufficient to make the speaker sound ridiculous. Why? Because in music’s parallel universe, to talk about tax policy or congressional gridlock is to spew incomprehensible nonsense. Since these utterances are unlikely to have inspired music in the first place, they sound ridiculous when set to music.

John Adams and Peter Sellars’s opera Doctor Atomic (2005) provides an illuminating example of this gravitational law, because of the strong contrast between the piece’s dreamlike elements and its more prosaic ones. The opera is a complex, collage-like critique of the history of the Manhattan Project; its action takes place in the days leading up to the “Trinity” test of the atomic bomb, and long stretches of the libretto consist of direct transcripts of conversations among scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. (I had the memorable experience of conducting Atomic in the Santa Fe Opera’s stunning outdoor theater in 2018, in a new Sellars production that was built specifically for Santa Fe. Sellars wisely left the back of the stage wide-open so the audience could see the lights of Los Alamos glimmering on the horizon.)

As is often the case in Sellars’s work, the men in Doctor Atomic are notably less empathetic, and less in touch with the world around them, than the women are. The women—Kitty Oppenheimer and Pasqualita, a Pueblo woman working as the Oppenheimers’ maid—communicate exclusively through poems: Charles Baudelaire, Muriel Rukeyser, a Pueblo lullaby. The men, by contrast, spout scientific jargon, bicker about military policy, and fret about how much weight they’re gaining. Only J. Robert Oppenheimer, Doctor Atomic himself, moves freely between these two registers. Among the scientists, he is capable of perversely antipoetic language (“the extreme pressures and temperatures reached in the interior of our explosion will not be high enough to fuse the hydrogen with either nitrogen or helium”), but when he’s finally left alone with the bomb, his monstrous masterpiece, he recites one of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets in a moving act of prayer and self-flagellation.

In the second act, during the tense countdown before the bomb’s test, the contrast between the men and the women becomes extreme. The two women, Cassandra-like in their prophetic skepticism about the coming detonation, sing excerpts of Rukeyser’s poetry to music that seethes with a hallucinatory intensity. It’s potent stuff; I remember going into a kind of trance as we performed these passages.

But the trance dissipated whenever we returned to the maledominated world of the scientists. The men in Doctor Atomic are myopic, self-important, dangerously capable of self-deception. One wonders, from the beginning, why exactly they are singing their lines, which so clearly belong to the register of spoken conversation. The answer is that, for the purposes of Atomic’s creators, it’s helpfully unflattering to force these technocrats to sing. Okay, Sellars seems to be saying, you can talk about letting millions of people die by pressing a button, but try singing it. A statement’s singability, for Sellars, is a test of its spiritual veracity. And as he knows, these lab transcripts fail the test. To sing them is in part to parody them: Adams’s music inflates the scientists’ utterances, which makes them more readily deflatable. (Remember those YouTube satirists.)

After a while, it seems almost cruel to force these poor schmucks to keep singing. We could tell from the outset that they’re fundamentally unmusical souls.

Opera transforms pain into pleasure.

This dynamic is a constant in opera’s dreamworld: some speech acts disintegrate and lose all possibility of being taken seriously; others, which would sound absurd if spoken, take on a life-and-death urgency. So, in creating an operatic libretto, the question that should underlie every word is not “Would a person really say this?” but rather “Does this need to be sung?”

*

The third law of gravity: opera transforms pain into pleasure. In opera, happiness is not only a sad song but also frequently a song of madness or blind, bloodthirsty rage. The whole art form depends on music’s power to make pain bearable, or even pleasurable, both to the listener and the participating artists: as W. H. Auden put it, “The singer may be playing the part of a deserted bride who is about to kill herself, but we feel quite certain as we listen that not only we but the singer herself is having a wonderful time.”

The ramifications of this power are complex and ethically murky. The line between empathy and mere voyeurism is an unstable one, and part of the uneasy pleasure of listening to opera arises from a pervasive, subliminal uncertainty: Am I empathizing with my fellow human beings, or am I just voyeuristically relishing someone else’s pain?

This ambiguity is a salient feature of opera’s foundational story, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, a tale whose central subject is music’s power to transform pain into pleasure. But it’s not clear whether Orpheus wields this power for good or evil. Orpheus’s backward look is opera’s original sin: by looking back, he subconsciously chooses the pleasures of lamentation over the possibility of saving his wife. And though this dynamic is at its most mercilessly distilled in the Orpheus story, it’s present to some degree in every opera.

__________________________________

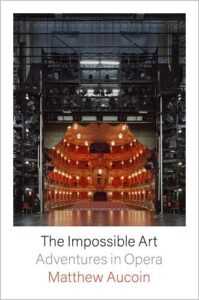

Excerpted from The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera by Matthew Aucoin. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Matthew Aucoin. All rights reserved.

Matthew Aucoin

Matthew Aucoin is an American composer, conductor, writer, and pianist, and a MacArthur Fellow. He has worked as a composer and conductor with the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, American Repertory Theater, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Music Academy of the West. He was the Los Angeles Opera’s Artist in Residence from 2016 to 2020, and is a cofounder of the American Modern Opera Company.