On Machines That Shit, and Fictional Characters That Do Not

Benjamin Hale Considers Cloaca, Orpheus, and Pooping

I

I have just published a collection of long stories titled The Fat Artist; in the title story, a performance artist decides to reverse the conceit of Kafka’s The Hunger Artist, setting out to eat as art. His stated goal is to becomes the heaviest human being in recorded history. Inside a glass box on the roof of the 1992 extension to the Guggenheim Museum, he sits naked on an enormous bed connected to catheter tubes and eats on display. The museumgoing public bring him food, and anything they bring him he must eat. “I became keenly attuned to the secret rhythms of the cosmos in the course of my consumption, digestion, and excretion,” he says,

I had to. I would of necessity eat very slowly, in order to prevent vomiting. Do not pause—I told myself—you may eat slowly, but you may never stop eating. This mantra I inwardly repeated to myself over and over as I ate. Just keep the food flowing. I learned how to keep the muscles of my bladder and sphincter permanently relaxed, so that it required no conscious effort of my own to expurgate my bodily wastes. My urine and feces slid easily out of my body and disappeared down the rubber tubes, vacuumed away into oblivion. The input-output relationship between eating and defecation, between drinking and urination, became as unconscious and as physically effortless as the inhalation and exhalation of air. My body was an ever-flowing continuum, connected at both ends to the material effluvia of the external world. I achieved a Zenlike state of serene hypnosis, a harmonious fusion of being and becoming, oblivious to all but the hands that brought the food before me to my mouth. In, out, in, out: like an element of nature, like a river, like the waters flowing forever and anon unto the sea, where it rises to the heavens and falls again to the earth, a never-ending samsara cycle of death and rebirth, entering and exiting, my body nothing more than a passive and temporary holding chamber for the things of this world.

In very small part this story was inspired by a trip I took in 2003, when I was a sophomore in college, to New York’s New Museum, where the Belgian conceptual artist Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca machine was on exhibition.

Delvoye’s Cloaca is an enormous machine he spent eight years developing with the consultation of engineers, chemists, plumbers, and gastroenterologists, which is designed to replicate the chemical processes of the human digestive system. The machine gradually turns real food into artificial shit. It is twenty-some feet long, and takes up a large room of antiseptically white gallery space. It looks like a Rube Goldberg contraption—a complicated chain of vessels, tubes, pumps. At the front end of it, someone stands on a stepladder and scoops food—real, valuable, nutritious, fit-for-human-consumption food of the sort that is in scarce supply for many people on this planet—into a clear glass funnel. The food slides down a glass tube and into the first of a series of chambers full of artificial stomach acid, bile, and water teeming with bacteria and microfungi. At each stage in the process, the food is further broken down, picked apart, dissolved, and reformed. At the very end of the system of connecting chambers, the material is dehydrated and compressed by a bellows-like device into a glass cylinder, beneath which a cold metal anus dutifully defecates impressively lifelike turds onto a thrumming rubber conveyor belt, complete with a gaggingly feculent odor. There is a control panel on the machine, covered in various knobs and dials by which one can modulate the levels of the chemicals in the system in order to produce different varieties of stool: one can set it to such-and-such a reading for fat, healthy, fibrous turds, and turn the dials to another setting to dispense diarrhea. The artificial feces were then vacuum-sealed in plastic packages stamped with a logo, and these were available for purchase in the museum gift shop. I did not buy one.

At the time, seeing this thing caused me to think of a lyric in the version of “John Henry” that Johnny Cash sings on Live at Folsom Prison:

Did the Lord say that machines

Ought to take the place of living?

And what’s a substitute

for bread and beans?

Do engines get rewarded

for their steam?

What most disturbed me about the machine that turned real food into fake shit was its sheer uselessness. Considering that it is perfectly good food that goes into it, the use-value of the thing is in fact a net loss for the world. It exists only to consume and to defecate, and produces nothing else. It does not use the caloric energy to throw a fastball, paint a picture, build a house, do someone’s taxes, or write a symphony. Nor does the machine derive any gustatory pleasure from the haute cuisine dishes the museum’s workers scraped with forks from plates into its gaping, tongueless mouth of glass. What other basic human needs could we relegate to automata? Might we one day build machines whose purpose is to sleep? To have orgasms? To have religious experiences? Will we stop thinking of machines as means to serve our purposes, but as ends in themselves? As beings to take over not only our labors, but our bodily functions, our pleasures—our moments of ecstasy and bliss? Would machines take over life from the living?

II

I seem to recall a joke early on in Don Quixote (although I’ve spent half the afternoon flipping through my copy of it and haven’t found it—perhaps I made it up) about Don Quixote refusing to eat or defecate on his first sally, because in all the chivalric romance literature he’s stuffed his head with, he cannot recall a single instance of a knight-errant ever getting hungry or needing to shit. There’s a similar joke in Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, in which a character steps through the life/narrative membrane of a movie screen and into the real world. Later, strolling through a shuttered amusement park, he says, “Too bad nothing’s open. I’m starved!”

“You are?”

“Well, I left the movie right before the Copacabana scene. That’s where I usually eat.”

“Oh, what am I thinking? Look here, I’ve got a whole bag of popcorn. You can have that.”

[eating popcorn] “Oh, boy! So that’s what popcorn tastes like. I’ve been watching people eat it for all those performances…”

A character is not a human being. A character is a mindless, bodyless idea shared by the imaginations of at least two people: the writer and the reader. Unlike a human being, a character does not need to eat.

Writers tend to train the reader’s eye onto the things that interest them, that matter to them. Faulkner seems to have spent much more time than I ever have thinking about the local flora—I swear every other page of Absalom, Absalom! has the word “wisteria” on it (or maybe he just liked the sound of the word). A.S. Byatt has a habit of lavishing description on her characters’ clothing, while other, less fashionably inclined writers are content to allow their readers to dress the characters in whatever happens to be lying around in the closets of their imaginations. Everything the writer does not put on the page does not exist, unless the reader provides it unasked. Brian Morton once told me that in his early attempts at fiction, he was so preoccupied with his characters’ emotional lives that he forgot to give them jobs.

Forgetting to let a story’s characters eat or shit is, I find, a tendency of those writing in the heroic (or propagandistic) mode. They are writers who turn our eyes away from the body in order to focus on the soul, or other instructive inventions. Just as Don Quixote can’t remember knights-errant ever ingesting or excreting anything, neither can I recall Batman ever eating a cheeseburger or taking a dump. The warriors for spiritual good have no concupiscence—in Catholic theology, the “lower appetites” of the earth and flesh: food, drink, and especially sex.

There is a chapter in Girigio Agamben’s The Open titled “Physiology of the Blessed,” in which he discusses the tricky problems medieval theologians had with whether or not there is eating or fucking in heaven.

The two principal functions of animal life—nutrition and generation—are directed to the preservation of the individual and the species; but after the resurrection humanity would have reached its preordained number, and, in the absence of death, these two functions would be entirely useless. Furthermore, if the risen were to continue to eat and reproduce, not only would Paradise not be big enough to contain them all, but it would not even hold their excrement—thus justifying William of Auvergne’s ironic invective: maledicta Paradisus in qua tantum cacatur! {Cursed Paradise in which there is so much defecation!}

Thomas Aquinas, on the other hand, solved this logical problem by asserting that the resurrection “is directed not to the perfection of man’s natural life, but only to that final perfection which is contemplative life.” Agamben quotes Thomas, from the Summa Theologica:

Those natural operations which are arranged for the purpose of either achieving or preserving the primary perfection of human nature will not exist in the resurrection … And since to eat, drink, sleep, and beget pertain to … the primary perfection of nature, such things will not exist in the resurrection.

So, according to Thomas Aquinas, there is no sleep, food, or sex in heaven—which does not sound like any sort of heaven where I would want to be.

Knights-errant do not eat, and nor do superheroes, nor do romantic matinee stars of the golden age of cinema (except at the Copacabana). Neither do angels, or God, or the blessed souls of true Christians resurrected in Paradise at the end of history. (It’s worth noting that pre-Christian literature is excused from all this terrifying abnegation: In Homer, the gods drink nectar instead of wine and eat ambrosia instead of food, as the Greeks, who saw no sin in consumption, could imagine immortality but could not conceive of beings that do not eat food or drink wine. Otherwise, what would be the point of living forever?)

Prose fiction, however, which at heart (or at least at my most favorite) is comic, prosaic, pedestrian, and earthly, makes room for the body—for ingestion, digestion, eructation, and evacuation. Leopold Bloom does it:

Quietly he read, restraining himself, the first column and, yielding but resisting, began the second. Midway, his last resistance yielding, he allowed his bowels to ease themselves quietly as he read, reading still patiently, that slight constipation of yesterday quite gone.

…as does Rabelais’s giant Pantagruel, who gets drunk and stands on the roof of Notre Dame, unzips his fly and floods the streets of Paris with his urine—take that, Church, State, priest, king, soul, the palliative lure of invisible promises, hero-worship and its many uses for us: I concu-piss all over you!

My point? I appreciate fiction that does not forget the body, that does not forget the whole world of the digestive tract, from the comestible to the scatological. Characters who must eat and urinate and defecate are closer to human to me, closer to the only thing worthy of worship: life.

III

(The following is a relevant excerpt from a work of fiction in progress. The main character is a musician named Oscar Greene, who has irritable bowel syndrome, a condition he shares with his author.)

Ears, eyes, nostrils, mouth, anus, urethra, and vagina. The male human body has nine macroscopic points of ingress/egress, the female body ten. The average number of pores in the skin of a human body is around 72,000,000. These are the points at which our bodies exchange things with the non-body world. Our orifices are the points at which our bodies interact with the material outside of them. We put material into our orifices, and it becomes part of us. We expel material from our orifices for various reasons: our bodies remove from themselves materials that are harmful to us or unneeded; we sweat to thermoregulate our systems, to cool our machinery.

The road from mouth to anus is long and winding. The material we put into our mouths and swallow must travel through thirty feet of tunnels and chambers. Teeth and saliva begin to break down the input material, which then travels through the esophagus down to the stomach, where bile and digestive enzymes disintegrate it into a mushy liquid called chyme; the chyme passes through the pyloric valve and into the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine; from there, the chyme oozes through long tubes of muscle that contract and expand to massage it along its way; the inner walls of the intestines are covered in villi, like tiny fingers, each one with microvilli, thousands of its own tiny fingers (this is to maximize surface area); the porous inner walls of the intestine absorb the useful nutrients in the material and incorporate them into the bloodstream, where they go on to fuel the organism that ingested them; the substance eventually passes into the next tube, the large intestine, which absorbs the remaining water and packs the solid rejected material into the colon, where it is stored until it can be pushed out of the body through the anus. In healthy adult humans, the duration of this journey varies from about 40 to 50 hours.

* * * *

Oscar Greene’s body had a troubled relationship with everything inside of it that lay situated between his mouth and his anus.

Something, somewhere between his mouth and his anus, was wrong with Oscar Greene’s body. Or perhaps it was many things. Acid reflux, nausea, bloating, gas, diarrhea. His body seemed to be almost at every moment expressing its displeasure with what he was putting into it, by sending belches up from below and long, whispery farts out the other end. He would eat, sending the worldly stuff into dark places he knew nothing about: he imagined them as hellish, steamy places of bubbling puddles, chemical gasses and miasmal mists. The underworld of himself. Who knows what goes on in there.

On good days, he could forget about his digestive system. His mind could wander away from what was going on inside of him for long periods of time, and then, after a smooth, painless defecation, he would stand and turn around to find a toilet bowl full of compact, muscular feces that were the warm, earthy brown of polished mahogany, and a pass over the orifice below with toilet paper would reveal not one trace, not even the faintest feathery brushstroke, of shit. But unfortunately, those days were more exception than rule. They were days of celebration when they happened. Most days, his gut felt as if a goblin were living inside it, whom the slightest irritant—coffee? butter? hot sauce? curry?—might at any moment awaken and send into a snarling frenzy, clawing and gnashing at his innards. On these days, his belly suffered a throbbing, consistent ache with occasional spikes of excruciating pain, like an exploding ball of knives. Hours after eating, he would either be fighting down vomit or holding back diarrhea in an irrational struggle to keep the nutrients inside of him.

AN ILLUSTRATIVE PARABLE:

(1.) Our mythologies are multitudinous with figures who descend into the Underworld (or ascend into the afterlife?) and return from it back to the realm of the living: Gilgamesh, Odysseus, Aeneus, Dante. But perhaps none comes so readily to mind as the great songster, charmer even of the King of Death, serenader of all things living and some things not: Orpheus, who crosses the threshold of Hades to bring back his wife, Eurydice. Orpheus sings to Hades and Persephone; they permit him to take Eurydice back to the realm of the living so long as he does not look back. Nearing the gates between Life and Death, Orpheus, feeling his love’s hand slipping in his, looks back, and sees her vanish again into a shade. He returns to Earth defeated and alone.

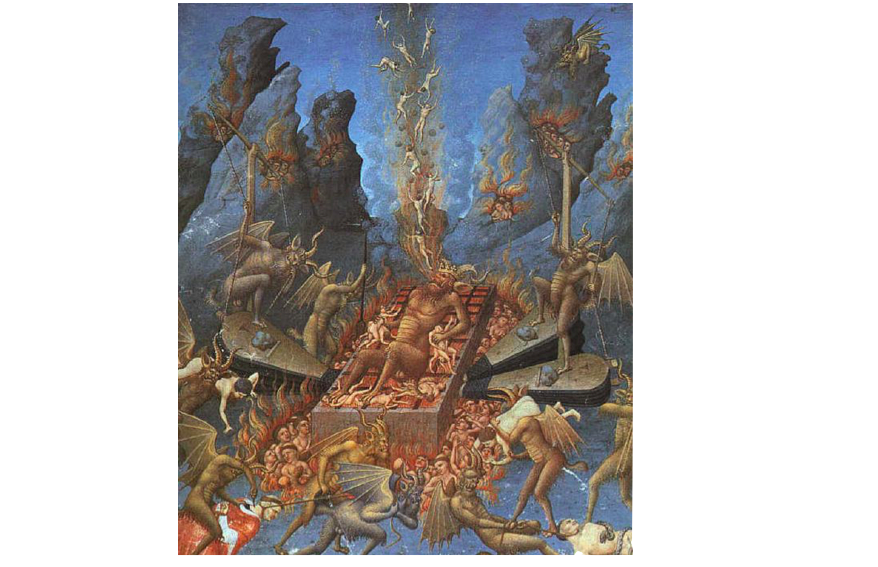

(2.) In medieval art, the entrance to Hell was often depicted as the gaping mouth of an enormous monster—the Hellmouth—which chews and swallows the bodies of mortals.

It is natural—isn’t it?—to visualize the entry to the realm of the dead as a mouth, and of the Underworld as a place of digestion. Our souls are food: we enter the great chewing maw, and are swallowed, where we begin to be digested. It takes time to break down and dissolve. Over time, we do, and we are fed back into the world.

It is natural—isn’t it?—to visualize the entry to the realm of the dead as a mouth, and of the Underworld as a place of digestion. Our souls are food: we enter the great chewing maw, and are swallowed, where we begin to be digested. It takes time to break down and dissolve. Over time, we do, and we are fed back into the world.

(3.) So soon after her death, Eurydice is still in the stomach, undigested enough that she may still be vomited back out intact. Orpheus journeys into the great mouth between world and non-world, down through the long throat of death, and into the stomach of existence, in which he finds Eurydice. Eurydice swims frantically in the cavernous pool of frothing fluid, thrashing amid teeming limbs along with all the other newly-swallowed. Luckily, it is still possible to rescue her, because she is such a recent arrival in the belly of death: the unlucky ones, those down toward the bottom of the pool, with all those souls struggling on top of them in the bilious goo, are being broken into the mush of fading human memory, and are about to pass through the valve at the bottom that sends them into the intestines, where they will be dissolved back into the Universe. Orpheus snatches his lover’s hand and drags her out, out, and up toward the light, struggling against gravity and the muscles that swallow, buoyed by uprising clouds of acid gas at their feet. But, almost at the top of the throat, the light coming into view on the back of the cavern wall above, he feels her grip on his hand slipping, and Orpheus looks back. Eurydice’s hand slides out of his, and with plaintive eyes and mouth rounded in a silent shriek, she falls back down the esophagus. But Orpheus is too far ahead—he cannot go back. The throat ejects him, and he tumbles forward, clawing futilely at the slick floor of the mouth, which spits him, whole and undigested, wet with yellow ooze, back onto the surface of the earth. Another belch, a grumble—and the mouth hacks up his lyre after him, which lands beside the outcast poet with a clang and disharmonious reverberation of strings.

Feature image: detail from Orpheus Sings for Pluto and Proserpina, Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1594

Benjamin Hale

Benjamin Hale is the author of the novel The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore (Twelve, 2011), the collection The Fat Artist and Other Stories (Simon & Schuster, 2016), and the nonfiction book Cave Mountain: A Disappearance and a Reckoning in the Ozarks (forthcoming from HarperCollins, 2025). He has received the Bard Fiction Prize, a Michener-Copernicus Award, and nominations for the Dylan Thomas Prize and the New York Public Library's Young Lions Fiction Award. His writing has appeared, among other places, in Conjunctions, Harper's Magazine, the Paris Review, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Dissent and the LA Review of Books Quarterly, and has been anthologized in Best American Science and Nature Writing. He is a senior editor at Conjunctions, teaches at Bard College and Columbia University, and lives in a small town in New York's Hudson Valley.