Ye Chun on Bilingualism and Wuwei Writing

"Words did not flow. They were squeezed out and then staggered on the page without conviction."

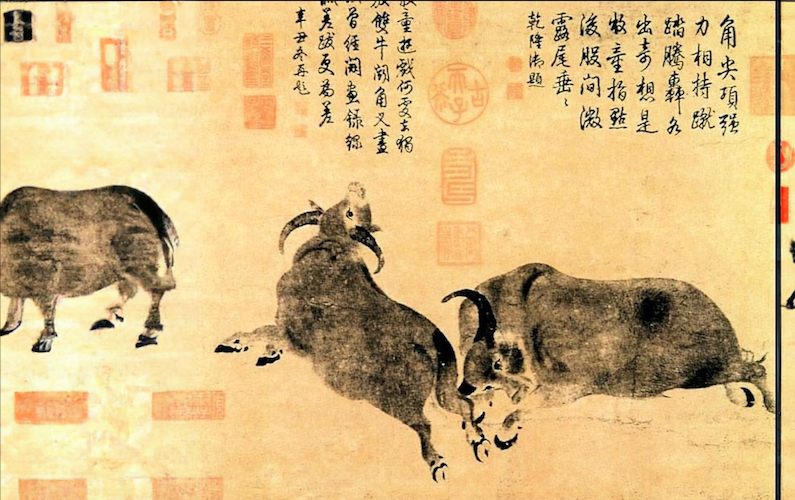

We read the story of Cook Ding in elementary school. He is an expert at cutting up oxen. He sees crevices between an ox’s bones and joints and inserts the blade of his cleaver lightly. Hu-la, the meat falls apart like a lump of earth. Joy fills him as he cleans his cleaver, which still cuts like new after nineteen years of use. He follows the Dao, and what he does is wei wuwei, do without doing—effortless like non-doing.

In my youth, I was skeptical of Cook Ding’s joy. I couldn’t quite picture butchering without hearing the predawn shrieks from the slaughterhouse not far enough from our apartment. It was a bloody, messy business, a far cry from Cook Ding’s breezy effortlessness. People strove. I strove. Every school day seemed to be lived for the college entrance exam. Even the morning qigong practice with my parents was meant to help me concentrate better for higher scores.

I studied English in college, a useful major in the economically reforming China. After graduating, I moved to Shenzhen, the special economic zone, and wrote and translated for the English Page, which was inserted in the municipal newspaper and was known as the “necktie of the metropolis” (if Shenzhen was a western suit). It was the mid-90s, and the city was deluged with all things West: midnight bars, rave parties, Big Macs, Guinness, Nirvana, marijuana. I strove to be worldly.

A few years of my restless working, consuming life, I felt a longing for elsewhere. I imagined a kind of disappearance, maybe in a remote town where I would be alone and finally meet myself. I would do nothing—just write and wander and learn what life was all about.

The thought translated into graduate study abroad, a more logical, and predictable, next step for ascendance. It was a plausible, even applaudable way of disappearing, a more complete one as well. In the last year of the last millennium, I found myself in a classroom in the heartland of America, wondering how the language I’d learned felt on my classmates’ tongue. I sat on a campus bench eating an apple. A squirrel looked at me sideways, didn’t seem to see me, only saw the apple, waiting for it to drop. For a fiction workshop, I translated a story I’d written in Shenzhen. The professor, who had come to America in his twenties like me, except from a different country decades earlier, suggested that I write an American story. I didn’t know what that meant, but wrote a story set in the studio I rented where the refrigerator made chattering sounds at night. I changed the Chinese names to Anglo-Saxon ones to make it American.

My first year of writing stories in English was far from wei wuwei. Words did not flow. They were squeezed out and then staggered on the page without conviction. In my second year, feeling no good at fiction, I switched to poetry, a more forgiving genre for non-native speakers, as it involves fewer words and has a higher tolerance for non-standard English. To mitigate the battle between the two languages, I wrote my first draft in Chinese and then translated it back and forth while revising. After several years of writing poetry like this, I tried fiction again. I wrote a novel in Chinese, about how social forces act upon two sisters, both of whom could have been me. I wrote quickly. Words I thought I’d forgotten or never possessed poured onto the page. On good days, I tasted wuwei. The perplexing, disorienting I disappeared. A coherence emerged that felt almost easeful.

I felt a longing for elsewhere.

Meanwhile, there was the business of making a living. After several temp jobs, and caring for a toddler, I returned to school for a PhD in the hope of getting a stable job. The ESL instructor decided I wasn’t fluent enough in English to teach Composition, even though I had taught a year of poetry during my MFA. Her class included a weekly tutorial where I sat in front of her desk, read passages out loud, and tried to make what came out of my mouth appear as unbroken lines on her computer screen—via some sort of software intended to rid non-native speakers of their accents. She was convinced that when English speakers spoke, their words were naturally linked. Frustrated by my broken lines, she asked, “Why do you want to write in English in America? Why not stay in China and write in Chinese?”

For one thing, she seemed to be speaking of striving. What I was doing, writing in a foreign language in a foreign land seemed reward-less, and therefore, self-defeating. We revere effortlessness. When we see a musician play as if their fingers were infallible or a swimmer swim as if water were their true element, we catch a glimpse of our own potential. But when efforts seem misguided or fruitlessly exerted, they are simply wasteful, like the way my instructor must have seen me—failing again and again to link the lines on her computer, and inevitably, failing to write well in a language that is not mine.

The summer after my first year as a PhD student, sitting under a century-old oak in the backyard of our rented house, I found myself scribbling in English in my notebook. The extensive use of English that year must have crowded out my Chinese, which until then had been the language I wrote freely in. A relief, since now I could skip the time-consuming self-translation when already there was hardly any time to write. It was also unsettling. I seemed to be losing my Chinese and I would never be able to write in English as if it were my native tongue. I would be stuttering, perpetually seeking the right word in my linguistic unbelonging.

The extensive use of English that year must have crowded out my Chinese, which until then had been the language I wrote freely in.

I ended up teaching composition, completing my PhD, and getting a full-time job—as a fellow PhD candidate had predicted, except for not quite the right reasons: “You have a book, you’re Chinese, you’re a woman, of course you’ll get a job.” In an interdisciplinary course I co-taught with a history professor on East and West encounters, I learned for the first time about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the country’s first immigration law that barred the entry of Chinese laborers and denied citizenship to the Chinese who were already here. I learned that without the Chinese laborers, the transcontinental railroad across the Sierra could not have been built, and approximately 1,200 Chinese railroad workers died building it. I was struck by my ignorance. How could I have lived in this land for almost twenty years without knowing these basic historical facts?

In the summer of 2019, visiting my parents in Guangdong, I told my father I was reading about Chinese in the 19th century America. He reminded me that his great-grandfather had helped build the railroad. The information was somehow new to me. What I had known was vaguer: my ancestor had labored overseas for two decades before returning home to build the two-story house my father grew up in. The focus had been on the two-story house, not the detail of his labor. Maybe this was because the blood-and-sweat railroad work evoked no glory or promised no redemptive wuwei, and the bloody purges and expulsions made his return a choice he had no power to make. Maybe shame resided in what was left untold. The legacy that had been erased in America, for different reasons, was also erased in China.

I read all summer, delaying the writing. I kept telling myself I needed to learn more. But at the beginning of the fall semester, during my pre-tenure research leave, I began to write. At first, nothing but dull words appeared, but after an hour or so, I felt an easing in my head and words began to flow. I wrote every day. Some days, nothing shone. Some days, the novel seemed to be writing itself.

Early the following spring, my daughter came home and told me a classmate had done a little song and dance in front of her: “I am coronavirus from Japan, hanging out with Chinaman.” When a week later, her school switched to remote, I was relieved. I had been afraid she would be asked, “Do you eat bats?” or get beaten like other Asian and Asian American kids were experiencing across the country. In the past, the question for her was “Do you eat dogs and cats?” which, like the one my former ESL instructor had asked me, had no good answers.

One day, I ventured out for a walk. A man standing by the duck creek yelled in my direction. I couldn’t make out what he was yelling. It could have been a version of “Go back to China!”—the ubiquitous rant hurled at people who looked like me. A not-so-distant echo from the rallying call shouted by mobs a century and a half ago: “The Chinese must go!”

I wrote my fear and anguish and anger into the novel about my precursor immigrants who were all too familiar with such yelling. Some of my characters decide to go back to China. Some stay put, to claim their space at whatever cost.

I wrote and when it went well, I forgot I was writing in a language not native to me. It didn’t seem to matter which language I was writing in, or where I was. I was simply writing, without striving to write. I disappeared into the world of my making, a safe place to be. And I felt joy.

__________________________________

Ye Chun’s Straw Dogs of the Universe is available from Catapult.

Ye Chun

Ye Chun is a bilingual Chinese American writer and literary translator. Her debut story collection, Hao, was longlisted for the 2022 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. She is also the author of two books of poetry, Travel Over Water and Lantern Puzzle ; a novel in Chinese, Peach Tree in the Sea; and four volumes of translations. A recipient of an NEA Literature Fellowship, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and three Pushcart Prizes, she teaches at Providence College and lives in Providence, Rhode Island.