On Learning to Take Author Photos Remotely During the Pandemic

Beowulf Sheehan Adapts His Art to a New Normal

Portraiture, as I knew it, was very physical, a constant moving of my body to suggest poses to the subject and change equipment and environments with my assistant. Most of my portrait sessions involved at least three participants: subject, assistant, me. Sometimes as many as ten people—hair and makeup artists, stylist, second assistant, agent, client reps—crowded onto the set, filling my studio with background chatter and music beyond my dialogue with my subject.

In-person media productions, the only kind I’d known, were banned in New York days into the pandemic. In September they were permitted again if one followed certain safety protocols. I had hospital-grade disinfectant. I had a HEPA/UV air purifier. Plenty of PPE. In-person commissions returned slowly. On September 30th, an email from the novelist David Hoon Kim arrived with “query regarding remote portrait work” in the subject line. “I am a writer living near Los Angeles in need of an author photo for my novel,” he wrote. After exchanging a few emails, I was confirmed to make my first remote author portrait.

I prepared as I would any author portrait session. I read David’s novel Paris Is a Party, Paris Is a Ghost. He and I talked about ideas and locations that spoke to them. Warm-toned, textured backgrounds, an element of separation in them as a nod to the novel. David’s partner Linda, who did concert and wedding photography but was curious about portrait photography, joined in, and we planned our full-day session. We’d photograph at David and Linda’s home, followed by on-location work on the grounds of the Segerstrom Center for the Arts and, just shy of a half-mile from there, at the Isamo Noguchi California Scenario sculpture garden. Working remotely meant new details: Charging and recharging batteries for all devices, staying online, and avoiding the public when working outside. Camera gear, laptop, and cell phone needed to perform and be kept safe all day. Talking and art directing would happen through Zoom. The frames would appear on her smartphone through the Canon Connect app, and I’d see them over Zoom on her laptop.

Our session started with what all pictures needed: Light. First light was 6:46 am and sunset 7:01 am for Linda and David. Our call time was 7 am (10 am my time). Putting the plan into action, their covered backyard deck and exposed garden were our first locations. Background cloth, chair, tripod, camera, Zoom on a laptop showing me the set as Linda and David built it, Linda’s smartphone facing the laptop camera and showing me frames as I guided her exposures and his gestures, the three of us working with the morning light to sculpt David’s face.

Discussing the next picture with Linda over Zoom, Segerstrom Center for the Arts.

Discussing the next picture with Linda over Zoom, Segerstrom Center for the Arts.

When it was time to leave home, it was time to recharge batteries and for me to go offline. Linda and David put everything in a cart, put the cart in a car, and drove. With a click, we were reunited, staring at Richard Serra’s towering, enveloping, ochre-toned steel Connector, outside the Segerstrom Center for the Arts. The sculpture’s swooping walls could pull into darkness, burst into light, or share slivers of both. Perfect metaphors for David’s novel. Juggling lenses, camera, laptop, cell phone, and distancing all (on the ground, inside the sculpture or between Linda’s feet outside the sculpture) from the passing public, Linda clicked away, David posed in and with the art, and I directed. When we felt our pictures were made, Linda and David refilled the equipment cart and walked on. I went offline again, and we remet online when they reached the Isamo Noguchi California Scenario. There were few visitors apart from us, and there were many works David felt had echoed his story. We got back to it, easing David into and against the sculpture garden’s pieces. With only one curious onlooker at the Segerstrom Center, to my surprise we weren’t stopped by anyone at the Scenario.

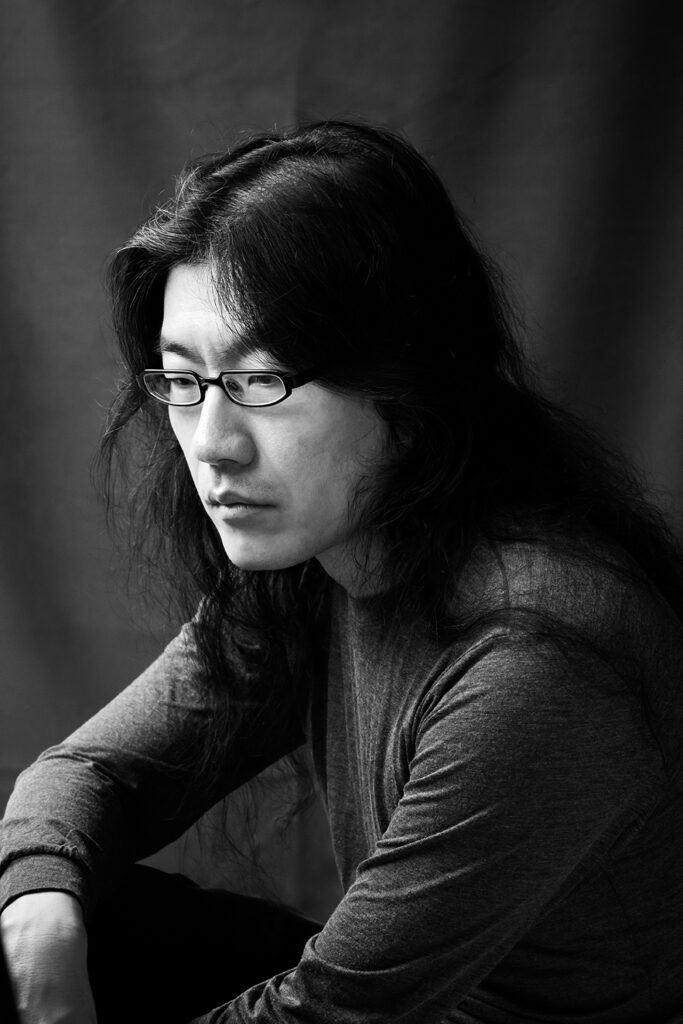

David’s author portrait, made inside Richard Serra’s “Connector,” Segerstrom Center for the Arts, Costa Mesa. David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

David’s author portrait, made inside Richard Serra’s “Connector,” Segerstrom Center for the Arts, Costa Mesa. David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

*

Another perspective with “Connector.” David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

Another perspective with “Connector.” David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

*

Photographed at David’s home. David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

Photographed at David’s home. David Hoon Kim by Beowulf Sheehan.

By the time we’d wrapped, we’d been on Zoom for seven hours. We’d made a broad body of work, seeing David compellingly, touching on the Movable Feast-like world through which his novel’s protagonist moved. “It was only my second ever professional photo shoot, so I didn’t really know what to expect,” David later reflected. “When I first wrote to Beowulf last year I had no idea if a remote author photo was even going to be possible, or that he would agree to it, especially given that he had never done one before mine. So I’m all the more gratified by the way it turned out.”

David’s picture at home, seen with exposure details on Linda’s smartphone over Zoom.

David’s picture at home, seen with exposure details on Linda’s smartphone over Zoom.

*

Four months later, an email with the subject line “a question for you” arrived: “Hi Beowulf, I’m publishing a book in July written by two New York Times reporters. They had originally planned to come to New York to have their photograph taken together, but Covid has made that impossible… My question is this: given the wonders of technology, is there any way to do a remote joint photo shoot, or is that an entirely fanciful idea? I’m guessing the answer is no, but thought it couldn’t hurt to ask!” Jennifer Barth, Executive Editor at Harper, asked me that question, on behalf of her authors Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang. Their book An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s Battle for Domination needed what would perhaps be publishing’s first double-remote author portrait. On the wings of my work with David Hoon Kim, my answer was yes.

Photographing Sheera and Cecilia involved multiple steps. The picture had to make the viewer believe they were next to each other, so we planned to photograph them identically. I turned my studio into an avatar for rooms in Sheera and Cecilia’s homes, mapping out distances among camera, light, and background. I arranged rentals of matching studio equipment with camera stores in San Francisco and DC. Over two days on Zoom, the authors and their families matched their “studios” to mine, setting identical lenses on identical camera bodies set to the same exposures, their lights the same diffusion, direction, and power as mine, the background paper the same color and distance from camera and lights as mine.

With lights, camera, and background in place, I was on to teaching Sheera and her family how the tools worked and how we’d use them. Their crash course in same-day studio photography lasted a few hours. Over Zoom, I saw what Sheera’s sister saw. I guided her clicks of the shutter, asked small changes to light and camera, and directed Sheera as she faced her sister and listened to her and my voices. “Sheera, turn just a bit more to your left. Let your eyes meet the reader’s eyes through the camera.” Along the way, Sheera’s mother, husband, and children all made cameo appearances along the way, sometimes to reset unintentionally bumped equipment or to wake up sleeping devices, sometimes to simply jump on set and embrace Sheera.

Day two of photography, Cecilia Kang and her husband in DC, Sheera in Berkeley, and me in New York over Zoom.

Day two of photography, Cecilia Kang and her husband in DC, Sheera in Berkeley, and me in New York over Zoom.

Cecilia watched Sheera’s session over Zoom, offering emotional support and learning what to do for her own session the next day. The second day of our two-day shoot, with Cecilia and her husband, was much more fluid thanks to the education of the first. Cecilia’s session ended as Sheera’s did, by photographing each journalist with her family (with the camera on a timer). Then we had a remote wrap party.

A week of editing and retouching to sew the two select images together followed the two days of capture. With Cecilia and Sheera reunited in a photograph, we had the picture Jennifer wanted: Cecilia camera left, Sheera camera right, the same light falling on them and shadow falling on the clean, gray background from the same direction (slightly camera right), the same catchlight in their eyes as they wore faces of resolve, standing barely an inch apart.

Cecilia Kang and Sheera Frenkel’s author portrait, with Cecilia in Washington, DC and Sheera in Berkeley. Photo by Beowulf Sheehan.

Cecilia Kang and Sheera Frenkel’s author portrait, with Cecilia in Washington, DC and Sheera in Berkeley. Photo by Beowulf Sheehan.

Looking back, Cecilia wrote, “I was actually skeptical that this could even work. Photography is incredibly personal and technical and doing it from afar seemed impossible. But Jennifer and Beowulf had a vision, and he walked us through every single step—over many hours—while taking no shortcuts and working with our crazy home conditions. The finished portrait was natural and gorgeous. What he did was magic.” Sheera added, “Like Cecilia, I was skeptical of how this would work. As hard as it was to get the technical set-up right, I have to admit that getting cuddles from my kids helped put me at ease during the shoot. Maybe home photo shoots aren’t that bad?”

Making Sheera and Cecilia’s picture involved ten people (Sheera, Cecilia, their editor Jennifer, their families, representatives from two equipment rental companies, my retoucher, and me). The technology and tools might have changed, but the most important elements of creativity—inspiration, communication, and collaboration—haven’t.

David Hoon Kim’s Paris Is a Party, Paris Is a Ghost is a tale of absence, its main characters removed from their cultures, one soon removed from life, and the other trying to stay in touch after the first has gone. Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang’s An Ugly Truth examines a company claiming connection while enabling deceit and division. Making these authors’ portraits through the challenges of the pandemic with the benefits of technology drove home the dichotomy of the last year+ of our lives: We’re meant to be together, except for now, when we’re not. And when we aren’t together, we still have tools to connect us. We have books.

Beowulf Sheehan

Beowulf Sheehan is a photographer of portraiture and performance in the arts and humanities. His work has been published in the likes of The New Yorker, Time, Vanity Fair, and Vogue and been shown at the Dostoevsky Museum, International Center of Photography, and elsewhere. He lives in New York City.