On Helping Tell a Palestinian Story as a White American Jew

Penina Eilberg-Schwartz Wonders What It Means to Share Space

Before a crowd of Israeli Jews at a peace demonstration—in the same square where an Israeli man, certain he was right, shot Yitzhak Rabin—Sulaiman Khatib stood on a stage. It was 2014, the war in Gaza not yet over. In Sderot, and sometimes in Tel Aviv, Israelis were ducking for cover. In Gaza, the death count was rising. That summer would see the deaths of approximately 70 Israelis, more than 2,200 Palestinians.

Looking down at a piece of paper, holding a microphone, Sulaiman wore a shirt that read “Combatants for Peace.” On his chest, two silhouettes threw their weapons behind them, as if recklessly. From the stage, Sulaiman began to speak to the crowd in his Arabic-accented Hebrew. It was a rare moment of solemnity for him, his words slow and deliberate.

“My name is Sulaiman Khatib. I’ve come from Ramallah. . . We, Israelis and Palestinians, call on both sides to act in courage and wisdom, to immediately stop the war in Gaza—and to start a serious dialogue.” He spoke the Hebrew words that had taken on their own life and rhythm from frequent use. “EIN pitaRON tsava’I l’sichsOOCH shelanu.” It meant what it always had: There is no military solution for our conflict.

When he stepped offstage, his phone began to ring. It was his friend Ra‘ed, calling from the Palestinian town of Yatta.

“I saw you on Al Jazeera live!” “Wallah, really?”

Sulaiman was surprised. Combatants for Peace received mostly international or progressive Israeli press. Palestinian TV didn’t often cover their actions. When it did, Sulaiman was sometimes called a traitor to his people; an ‘asfur: the Arabic word for bird that, for many Palestinians, meant a spy for the Israelis. Someone who, among other things, normalized the occupation, practiced tatbi‘a.

For a moment, Sulaiman felt a little afraid to go home to Ramallah. It only takes one stupid person, he thought. But by this time, he’d grown accustomed to feeling fear and meeting it—or sensing it and burying it. It wasn’t always clear which acts of imagination and erasure were needed to build a new story from an old one.

Two years later, a bit of wind blows as Sulaiman drives me down a West Bank road. The sky is darkening as we approach a famous junction near a number of Jewish settlements. Young Israeli soldiers stand at four corners, guns on their shoulders. As we drive by, Sulaiman’s shoulders inch toward his ears.

Sulaiman Khatib—or Souli, as many know him—is a Palestinian peacemaker from a village northeast of al-Quds, the Palestinian name for Jerusalem. He is cofounder and codirector of a binational nonviolent movement called Combatants for Peace, created by Israeli and Palestinian ex-fighters and ex-prisoners. He is a person who’s been through much, who seems able to lightly hold burdens that would bring others to the ground.

Soon after we pass the soldiers, Souli turns to me and smiles. My jaw is clenched, not yet ready to let go. Ajaki, he says, laughing out his favorite word. It’s a play off of Arabic slang from the streets of al-Quds, a word that moves between meanings, from “You get it?” to a nod of agreement. But the way Souli repeats it—like a song, or a punch line—it seems to mean nothing at all, or too much to name. His hair bounces over his eyes. When I first met him, it was shaved close to his head.

it’s been almost fifty years since Israel took over East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza; over ten years since Israel withdrew settlers from Gaza, but kept control of its borders and so much else.

We are headed somewhere, but we’re not sure where. It’s something Souli likes to do sometimes: get in the car at night and drive, without any destination, without any sense of what will come next. In this way, Souli’s driving seems like a kind of dreaming, a thing he does often. It’s linked to his way of existing firmly in reality while somehow escaping it entirely, living somewhere else, somewhere others can’t quite find him.

Where he is now, in reality, it’s been almost fifty years since Israel took over East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza; over ten years since Israel withdrew settlers from Gaza, but kept control of its borders and so much else. Souli is not sure how many years it’s been since he acquired his nickname. He’s not sure how many years it’s been since he was only Sulaiman.

For years now, Souli’s fans have told him to write his story. “It’s so cinematic,” they say and touch his shoulder while he smokes.

“They think I’m a visionary,” he explained to me once, grinning.

People do think this, I’ve seen it, and it’s because of what happened after one big bang of a moment many years ago, when at the age of fourteen and five months, Sulaiman stabbed an Israeli and was sentenced to fifteen years in jail. The length of his life until then.

Some people talk about him as if he were a prophet because, when he was released from jail over ten years later, he went searching for a way to participate in joint nonviolent activism and reconciliation with Israelis. Among many other things, he worked alongside a handful of Israelis to create Combatants for Peace, resisting the occupation and modeling a shared, peaceful future. Because of this, some people read his life as a textbook for transformation. They want it written.

“Why not have someone write the book in Arabic?” I’d asked him at the beginning.

“Palestinians know this story,” he said, waving his hand at a nonexistent fly. “Palestinians know that za‘atar is a religion, that land is a religion. They know what the olive trees, figs, and pomegranates mean to us

And he’s right. Some parts of his story—the violence and fear, the redemption and lack of it, the sacredness of land and of memory—are old news to Palestinians. A person does not need their daily reality narrated back to them. But Souli’s relationship to reality, as many friends have pointed out, is a bit strange. There’s something different in his way of seeing, and it doesn’t seem so only to me—a white American Jew—but to many of the Palestinians and Israelis around him.

Some people talk about him as if he were a prophet.

Strangeness has always seemed to me like a path toward truth or, if not truth, some better version of our world. So it was Souli’s strangeness that made me finally say yes when he asked me to write this book, or to help him write it. At the beginning, it wasn’t clear to either of us what he was really asking of me.

“We’ll see!” he said the day I agreed to work on the project, sitting in a café in San Francisco, blinking at all the light coming in. “Life is a journey!” he said, as if in answer to a question I hadn’t asked. Laughing, he picked up his fork. I rolled my eyes. He often said things that would annoy me coming from anyone else, but somehow, when he said them, they were true. I took a bite of his banana bread. I laughed, too.

I met Souli in 2006, in my mother’s house. When I walked into her wide-windowed dining room, and saw the lean man slouching in a chair, legs crossed, I knew very little of him.

“We have the most amazing new friend,” my mom, a rabbi who speaks in capital letters, told me. “He’s a Palestinian peace activist.” At the time, my mother, the first woman ordained by the Jewish Conservative movement, was engaging in dialogue about Palestine-Israel. It was a tense time for us, filled with many painful conversations about Zionism in which I angrily tried to unravel something I knew was precious to her, something she hoped would stay precious to me. I argued that it was not possible for a state to be both Jewish and democratic; she argued that no state (and no democracy) is perfect, and that the Jewish people deserve a safe space in the world to grow and govern—just like all other people. Our conversations pushed her further along a path she was already traveling, seeking out alternative narratives. Souli’s story was one of many beginnings for her. It was a story she could hear.

I don’t remember much of that initial encounter. I remember Souli, with tight, dark skin and close-cropped hair, getting up from his chair to shake my hand. I remember we ate and joked, that I invited him to come see my friends play banjo and musical saw in a café.

I remember later that night, when I went downstairs to fetch a book or something else I’d forgotten, and Souli was there, standing in the doorway of my younger stepbrother’s room. He smiled at me, said goodnight.

Behind him, I saw my stepbrother’s bed and the full-size Israeli flag hanging over the headboard.

“They have you sleeping there?” I asked. “Under that flag?”

I was so angry. They couldn’t have given him someplace else to sleep, or taken down the flag?

He laughed. “It doesn’t matter, habibti, calm down.”

I didn’t know it then, but this would be the first of our many political disagreements.

It wasn’t until two years later that I heard him tell his story. He wrote to tell me he’d gotten another visa to the US and would be giving a talk in Berkeley. He wanted me to come. When I got to Cafe Leila, I hugged him and sat with a bunch of mostly white, gray-haired people in their fifties and sixties. Amid the sound of forks on plates and scraps of conversation, he began.

I don’t remember what he said exactly. He changed focus erratically, traveling from place to place without warning. He spoke about stabbing two Israeli soldiers. He made jokes about jail—“Now I’m a couchsurfer, but then I was a jailsurfer. They took me from jail to jail, so I was traveling for free!” I sat there wondering at the nonchalance of his storytelling. He was light when he talked about his history; he didn’t place weight on anything.

When he finished, people clapped and asked questions. Someone wondered how he kept going, even in the darkest times. “I had to have something inside myself,” he said, “to know there was part of me living outside the jail.”

I saw it in him, how he seemed able to tear down anything in his way. Not with violence, but with something metaphysical, alchemical. He acted as if certain things that appeared solid were just a mirage. I wanted to know more about it, this physics-defying capacity. I wanted to know what it meant for him to transport himself elsewhere, to walk through walls. And I wanted to know whether anyone could follow. Or whether, for some, the walls stayed solid.

After his talk in Berkeley, before he flew to the next place, Souli and I spent every day together—walking, sitting on trains, making sure we never felt hungry, arguing about Palestine and Israel. I wanted him to be angrier; he wanted me to see the traditional Israeli narrative, too, to understand not only the occupation but also the mistakes Palestinians had made along the way.

After he returned to Ramallah, we stayed friends online. Though he often asked me to visit him, I never did. I’d been working intensely on issues of peace and justice in Palestine-Israel, yet I hadn’t visited the Middle East since the week-long vacation I took with my mom when I was ten years old. I’d never traveled to the West Bank or Gaza.

He was light when he talked about his history; he didn’t place weight on anything.

Time passed, and our communication grew thin. Our exchanges were limited to brief messages with little in them: a cartoon face or a heart, and nothing else. So I didn’t take it very seriously when, years after our last meeting, Souli sent a Facebook message asking me to help him work on a book. I said no. I didn’t think I was the right person for the job. I was neither Palestinian nor Israeli, and this meant there were many things I could not know, the knowledge that comes from living in a place. I was a leftist, perhaps not someone Israelis would feel moved to listen to. And I didn’t understand what Souli meant when he said he wanted to incorporate “my story,” too. I didn’t like the idea of a white American Jew telling a Palestinian story. I could hear the critiques. It’s his story. Get out of the way. It’s not for you to tell.

He wrote multiple times, and I said no just as many, until he was there—sitting across from me in a café in San Francisco. Seven years had passed since we’d last seen each other.

Over a small plate of banana bread, Souli asked again. He wanted me to help tell his story, to weave in Israeli stories, and my own—not to forget the importance of American Jewry in this conflict. As I listened, as time passed in its strange way, I knew that he was asking for the impossible. I knew that the result would be a tangled book, knotted with starkly unresolved issues of representation. But I also knew that the book’s questions of ownership and form might have something beautiful and distinctive to say about who Souli is, about the place he comes from, about what has happened there.

I looked out the window and turned back when I felt his hand on mine. He pressed it, offered a question: “How can these two narratives—Palestinian and Israeli—exist in one homeland?” He shrugged as if there were little left to say. “That’s the big question we have to share.”

This book, a vehicle for telling (one version of) Souli’s story, takes that question and peers at it through the lens of a larger and messier question: What does it really mean to share space?

When I arrive in Jerusalem/al-Quds to work on the book, it quickly becomes clear that Souli and I want to discuss different things. He avoids talking about jail, and instead speaks repeatedly and in generalities about what I already know. He moves quickly to other people’s stories, wrapping them into his own, picking them up along the way—like the lucky coins his father used to spot on the ground. Throughout our conversations, we struggle with each other over which past is most important to tell. In many cases, he prefers to ignore the past and tell only stories that point toward the future.

I didn’t like the idea of a white American Jew telling a Palestinian story.

This may have something to do with his tendency to look outside the frame, and, in a sense, outside of language. He speaks fluent English, but translated directly to the page, something essential in his words seems lost. In this book, to simulate the fluency he communicates in person, I will quote him while “correcting” his grammar, smoothing his syntax, making his tenses match. I want him to sound how I imagine he sounds in Arabic—though it’s only an imagining. I understand these changes as a kind of trespassing; he doesn’t.

Where there are holes in his narrative—so many things Souli doesn’t recall or doesn’t want to say—I slip into them, imagining my way into the small gestures of the story. These are intrusions Souli reads and approves before they make it into the final text. Because he wants his story—especially the beginning, before jail—told as story.

He doesn’t remember (and I can never know) exactly how hard he could kick a soccer ball, precisely when he first thought to use violence as resistance, the way he waved his hand at his mother when she asked him questions. Though he remembers his aunt telling him she could predict the weather, he can’t recall exactly how she told him. To speak of these things now, as story, is to imagine them. And yet, they happened.

So when it comes to his experiences, I tell the story based on what he’s told me, but imagine my way into certain minor details, the way he’s learned to imagine himself into the stories of people who’ve lived very different lives than his. All past dialogue is reimagined rather than explicitly remembered; the same is true for the exact sequence of events and duration in which they occurred. And due to the incredibly sensitive nature of this material, we have changed some names to protect the identities of those involved. Though what follows is faithful to the conversations I’ve had with Souli and with many others, it is not a work of history.

I am made nervous by all this slippage, but Souli remains unworried. Maybe it’s already clear to him how much memory is an act of interpretation, how every telling requires intrusion. Even when he relates his story, in his own voice, he’s only telling versions. That’s how it is for all of us. Developing a story is the act of deciding what to emphasize, what to leave out. And Souli doesn’t think this is a bad thing. On a collective level, he struggles both with and against this phenomenon to build a story—a third narrative—that includes Jewish and Palestinian histories, and all the places they overlap. His whole life has led to this reimagining. This, he thinks now, is how the world will get better.

When I talked about this act of imagination with a reporter, she looked at me with sharp eyes and told me that the Palestinian story is very real and has been ignored for a long time. I remember her saying, “It doesn’t need you to imagine it.”

Reliving this moment, I feel her words physically, a sharp pain in my stomach. I see her as she might see me: another Jew occupying Palestinian space. I see myself this way too, sometimes. Which is why I hope to make this occupation more visible, to remind myself endlessly that my presence here, even if I were to hide it, changes the story Souli tells. Making myself invisible won’t erase the power I have, so I would rather see it towering above me. It serves as a reminder that this book is a place where the two of us are sharing space. A reminder of the responsibility that Souli has given me: to shape how he is seen and even, as I would find sometimes, to shape how he sees himself.

Power travels across so many lines, and I’ve decided there is no neutral place from which to write. A book is a place full of danger—of a man’s story overtaking a woman’s, of a European Jewish story overwriting that of a Palestinian.

When I tell Souli what the reporter said about imagination, he laughs. He tells me to relax, that Palestinians are not just victims, that they have at least one enormous power: to make Israel legitimate in the eyes of the world, or not.

Among others, this is one of the powers Souli has over me.

____________________________________________

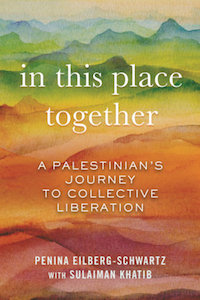

Excerpted from In This Place Together: A Palestinian’s Journey to Collective Liberation by Penina Eilberg-Schwartz and Sulaiman Khatib (Beacon Press 2021). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Penina Eilberg-Schwartz

Penina Eilberg-Schwartz lives and writes in the Bay Area. She has worked on issues of justice in Israel-Palestine with several organizations and is a member of IfNotNow, a movement working to end American Jewish support for the occupation. She is an alumnus of LitCamp’s juried writer’s conference, the Logan Nonfiction Fellowship and the Alley Cat Books writing residency. With her partner Marty Piñol, she co-wrote the chapbook Everything in the speaking of it (Alley Cat Books, 2019), an exploration of Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse written through redacted poems (omitted from the chapbook), prose poems, and essays-as-bookends. In this Place Together is her first full-length book. She is currently working on a novel as well as a book-length essay about the myth of the Jewish nose.