On Grief, Pizza, and the Power of Food to Evoke Memory

Adam Dalva Remembers His Brother

1.

My brother Robert and I grew up on Manhattan’s East Side. Some afternoons, we’d go to a deli—he’d get a stack of Genoa salami on an untoasted plain bagel—or to a diner for a hamburger. Usually, though, we’d stop in at the Ultimate Pizza, a below-ground hole in the wall on 57th and 1st. If you look at the Ultimate’s Yelp page, you’ll see a photo of my mother on the sidewalk holding our long-dead Maltese.

My brother and I would always order a large half regular, half pepperoni. A simple pie, sweet-sauced and oily, which we’d take home. When I think of pizza, I think of those afternoons with my brother: Pardon the Interruption; green bean bags; the space-age boot-up sound of our Sega Dreamcast.

Strange, but often remarked upon, is that food is the pathway to memory. Stranger, I’ve learned, is that when memory is distorted by loss, the food distorts too. Pizza, which I’ve always loved for its humbleness, has become redolent of grief.

2.

My brother died eleven months ago. Ever since, unfathomable depression, nightmares, screaming at random moments in the car. He had been mentally ill for years, but despite our frequent blowups, he was my friend. In his adult life, he mainly ate pizza. The simple kind: Domino’s, after the Ultimate closed. One of his issues with me was his supposition that I was a phony, as evidenced by my adult fondness for artisanal pizza. He felt that I didn’t actually prefer pies with, say, honey and hot peppers.

But then, he hated all the ways that I had changed. His was an ouroboros life. Hospital, childhood home, rental apartment that he’d destroy, hospital again. Every outward motion of mine—my marriage, when he had no girlfriend; my teaching job, when he kept getting fired; my publications, when he never could get past the first pages of his decade-long attempt to write a paper on semiotics—emphasized his own stasis.

Strange, but often remarked upon, is that food is the pathway to memory. Stranger, I’ve learned, is that when memory is distorted by loss, the food distorts too.Removing myself from our shared childhood forced him to notice our differences. And now that he’s removed himself from me, I notice him everywhere.

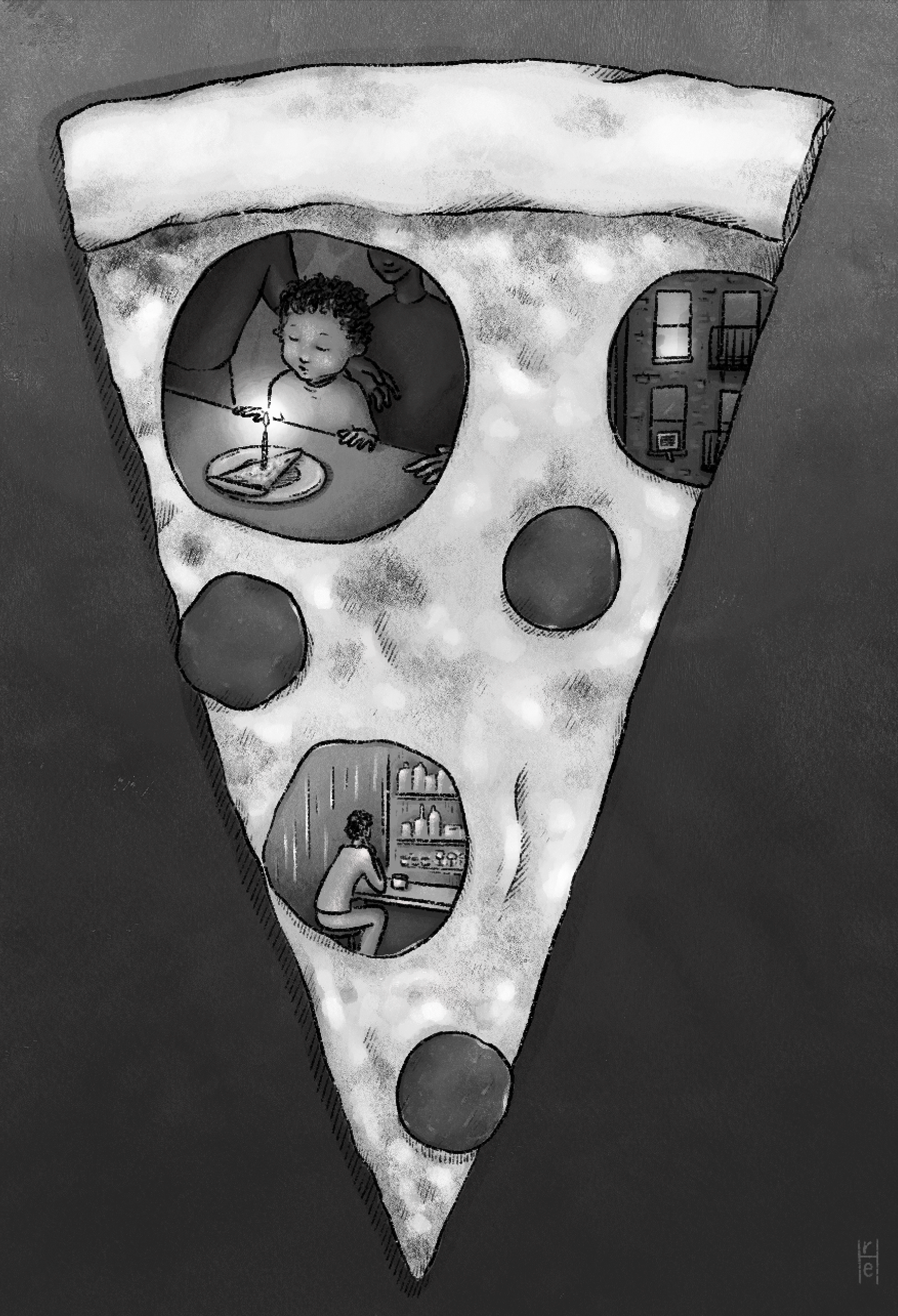

Illustration is by Rhe Civitello.

Illustration is by Rhe Civitello.

3.

There’s a word in German, “Kummerspeck.” It literally means “grief bacon,” but it figuratively means the weight gained after tragedy. I find this word a comfort. For some bereaved people, the shock to the system—and my brother’s death was a shock, though I’d been fearing it for many years—can lead to metabolic issues.

My metabolism was already bad, a lifetime of judgmental changing room mirrors. My brother, though, as he enjoyed pointing out, had an athletic build. Until the last days of his life, nothing stuck to him despite his pizza-centered diet. I’ve always been careful about my eating, salads and low carbs, but my habits disintegrated this year.

I haven’t stepped on a scale since March, but I know it’s bad. The face in the mirror is warped, distorted. Like my brother’s in the last selfies he sent me.

4.

The novel I’ve been writing since 2020 is about my brother now. Everything is. My book reviews, my fiction. My marriage. My dog. Even pizza, that simple canvas of dough, cut into eight.

5.

Grief, like food, plucks at seemingly random memories. I’ve been wrecked this month by that Sean Kingston song at a retro prom party, by a certain street corner in Paris where I once watched fireworks with my brother, by a waiter wearing one black glove, by the Cary Grant movie Charade, by a man in a restaurant who had a particular (beloved) way of holding his head. I started playing a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles video game at one point this fall, but had to stop when a turtle, dying, sprung back to life when he found a digital pizza pie.

6.

A few years ago, I broke up with a super taster, someone with way too many taste buds on her tongue. There’s a thought that this mutation is a genetic necessity, because in every group there should be someone who’s able to detect spoilage. She loved simple things—white rice and chicken nuggets, strawberries, the diet of a child. She’d experience synesthesia when she ate. Vinegar, raw foods, or anything fermented would make her feel so ill that she’d become mute for hours.

I’d wanted to write about this while we dated, but I hadn’t yet learned how to capture something so beautiful in prose. Although now, because we broke up, it is not as beautiful. Perhaps writing is waiting for things to go bad.

My brother, my-ex girlfriend suspected, was probably a super taster too. He had extremely intense reactions to most flavors, spitting and gagging. Some childhood nights, while he slept, my dad would whisper in his ear: “I like noodles.” But he never did, nor jelly donuts, nor any food that touched other food, nor anything raw or fresh or bitter. The more processed, the better.

When he became a de facto shut-in, I’d sometimes find his pizza boxes on the stove. Inside: discarded mozzarella. All cheese tasted spoiled to him, so he’d scrape some off with every slice, then I’d scavenge it. (Am I scavenging him now?)

7.

On what should have been my brother’s thirty-third birthday, my family and I ate pizza in homage to him. And I swear it, I swear, that when the cardboard boxes opened, there he was, little boy, candlelit, big-cheeked and long-lashed, gazing with ardor at his shimmering pie.

8.

I recently helped a well-known journalist set up a Zoom call with students in Bulgaria. After the event, he took me to a restaurant on the Upper East Side. This was the kind of hifalutin life beat that my brother would have loathed.

As we tucked into the salmon and spinach, he asked if I had siblings. I answered him the only way I have managed so far: “I did.” The journalist’s reputation as an interviewer is deserved. Everything was soon spilling out of me, things I’ve never told anyone.

Afterward, shaken and a bit sad, I walked to my parents’ apartment, where I’d arranged to spend the night. And I saw, to my surprise, that the Ultimate had reopened as (I hate to report this) Kiss My Slice. I walked in and got a slice of pepperoni. A beautiful slice, sweet with tomato and a bit too bready. The best thing I’d eaten in a year.

______________________________

Cake Zine Volume 3: Humble Pie is available now.