On Finally Finding an Authentic Voice (After Writing Several Dozen Books)

Mark Scarbrough Takes the Scenic Route to Memoir Writing

Want to write a memoir? Every writing coach will tell you to find an authentic voice, words that carry your soul. The truth demands it. Readers, too. So don’t start here: lunch out, Manhattan, white tablecloths, a steak house, strictly old school if just six years ago. My husband and I are celebrating our twentieth-sixth cookbook. He’s the chef, I’m the writer, we’re out with our agent. We’re also across the street from the Food Network, the behemoth that controls our industry. But not us. We’ve worked hard and continued to publish, daring the odds. Our reward: T-bones, plummy red wine, a throwback to older times in the book business. We linger three hours.

When the plates are cleared, my husband pulls his earlobe, our middle-age semaphore for “need to pee.” We’ve got a long ride back to New England. He excuses himself. Our agent starts to pack her leather bag.

The writer’s life is insecurity writ small, a spidery script tattooed on the inside of your eyelids. You can read it when you close them. So I don’t. I look around the room, breathe it in. Tipsy and well-fed, I say, “You know”—already wordy—”I’ve always had this strange relationship with books.”

She thinks I’m talking about our cookbook career.

“Jane Austen,” I clarify. “F. Scott Fitzgerald.”

She cocks her head, as if I’ve brought up Aquinas at the atheists’ ball. I shift my tone inward. “Combative,” I say. “Not exactly rational. Voices. In my head.”

I’m flailing, starting to overwrite, just as I do in cookbooks when I can’t quite articulate what cumin does for chili.

“I blame William Blake,” I say. “Probably everything I’ve read.”

She’s read a lot, too, although I have no idea if she knows about the frizzled connection between sanity and words.

Probably not because she reverts to imperatives: “Put something together. See if you can get it placed.” She mentions a back page feature in Publisher’s Weekly, where authors and editors rant about the industry.

I do: write it, place it. To her astonishment. Mine, too.

She calls me up and says, “Let’s begin.” Did I hear a sigh? She doesn’t seem congratulatory. But I set to anyway. Six months? How long does it take to write about yourself? Bruce and I can crank out a cookbook in that. And I know myself better than chili. Okay, seven months.

First, I write a section about preaching the gospel at county fairs, then another about the time I saw William Blake on a road outside of Waco, Texas. That’s the crux: an adopted kid who never fit in with his fundamentalist family, who started reading the great works of Western literature, who fell off his legally appointed timeline and into thousands of others, and who ultimately had one… no, several psychotic breaks because he replaced the incessant stream of God’s words in his head with those of lesser, literary gods, but gods nonetheless.

I send these two bits to a writer friend. We go out for an unagented lunch of soggy sandwiches.

She hands me back unmarked pages. “Where did those authors live in your body?”

I don’t know. I don’t know how to know. I should probably write a novel. I turn my fragments into chapters about a kid who finds the delights of literature while preaching at swap meets. George Eliot meets Flannery O’Connor.

“I thought you were writing about yourself,” my friend says over another soggy sandwich.

“I am!”

Her father wrote poetry in Homeric Greek. I trust her. She points to the main character’s name. “Alex?”

“I always wanted to be called Alex.”

“Yet you’re not.”

I take the hint. I should be writing a first-person novel. It grows to three hundred pages. I get my bookish “I” all the way through college. Only forty years to go. But at least he’s now read Chaucer.

Yet the thing’s still not right. I thought I got narratives because I get recipes, which are Aristotelian: beginning, middle, and end. But cookbooks are all kitchen and dining room. Personal narratives are living room, bedroom, even bathroom. Plus, I’m trying to explain something about words as dangerous, canonical books as threatening, their plots the shards of lunacy. My husband and I publish cookbooks for QVC, but now I’m sailing back to wild waters.

I go back to a memoir. A year (and a cookbook) later, I’ve got a manuscript. I explain how you can put together a self out of the great books.

You, unfortunately. Not me.

My agent says she has a few questions. Would we come to New York for dinner?

In a faux-tropical restaurant under the High Line, I find out her questions aren’t for me. They’re for my husband. “Are you okay with what he’s writing?”

I hear the whine in my head. Don’t you like the part when I. . . ?

I don’t verbalize that. It’s too raw, even for a memoirist. Instead, I down more booze, then launch into a hilarious story about forcing my ex-wife into a mind-bending lie about infertility to make her fit the Henry James plot I wanted us to live.

Nobody laughs.

“Put that in,” my agent says.

I do. I also tell about my dissertation advisor who was so nuts he thought I was the bodily resurrection of Natty Bumppo. And about landing a job at a Catholic university where I was forced to fish the tenured monks out of gay bars on the weekends. And about finally trying to be whoever the hell I am without other voices in my head.

My agent doesn’t praise my writerly heroism. She hires a freelance editor.

Two years pass in a blur. More cookbooks sold and a constant rewrite of my memoir. First, it should be shorter. Under 80K words. Then longer. I turn it into a three-volume set.

“You lost the arc,” my agent says.

Write, cut, write, cut, until something happens, seemingly despite me and because of me: my own voice emerges, gets stronger, and becomes the reason for the words. Not a wonky cookbook voice. Instead, a voice made out of stuff knifed up from inside me at bone level. It’s all jagged. Less sentence than clause. The verbalization of pain in the body as well the mind. That’s when I hear the magic phrase from my freelance editor, stated in the canonical babbling of my life: “Reader, I loved it.”

My husband and I publish cookbooks for QVC, but now I’m sailing back to wild waters.

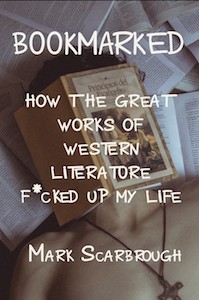

“Bookmarked: How Great Works of Western Literature F*cked Up My Life.” Documents are prepared. Briefs are written. Query letters are sent. Great expectations! Except the clock on my laptop tick-tocks the minutes, the hours, then the days, months, and years when nothing happens.

“You should read these rejections,” my agent says.

I don’t. She does. All praise, no sale. Words like “Pulitzer worthy” followed by “we can’t.”

Years before, I’d left academia, abandoned the chapel of the great works. I became a mass-market success. Then I clawed my way back into that literary world where quirk mattered, where voice was honed. This time, even mine. But along the way, something else had happened, too: My cookbook life had taught me that publishing is about measurable, monetary success. What’s more, I always felt like a fraud. My husband’s the chef. I just write the books. Not memoirs. Certainly not novels. Who was I kidding? No one but me. In other words, I’ve finally become something I’ve felt implicitly all along but still haven’t been as an author: a bookish failure.

Which becomes an open secret among our friends. It starts as looks: down, maybe a little to the side. Anything said happens after the second bottle of wine. “And your book?” It always trails off. The candles on the table twinkle.

When we sell another cookbook, people stop asking about the memoir.

For half of my life, I knocked together my consciousness from everything I read, jousting with Cather, swinging at Faulkner. Then I became the writer of books that told what my chef husband created in the kitchen. And now? Well, I’m no longer a ventriloquist’s dummy. Nobody’s hand is up my back. Or down my throat. Being a failure is actually a relief. First off, it’s understandable. They make movies out of sad-sack writers. Plus, in our cookbook career, I’m always second, the name after the “and.” That’s where I deserve to be. I don’t have to make it up. I can just live it. Like I do the rest of my life.

Because I’m an adopted kid. I’ve always lived with the identity handed to me by a judge, by law: Here’s your family, your life. For a while, I dared to create my own plot, write my own voice. But really, I should take what I’m given, the way I ate mom’s olive-loaf sandwiches in third grade. It’s more natural if my identity is ready-made. This cookbook thing was probably a fluke. I just married the right guy.

Another year passes. I’m deep into the editorial morass for our latest cookbook, mired in manuscript queries and self-pity. I head upstairs to take a shower when my cell rings. The caller ID says “agent.” I’m naked, so I answer. How else would a wasn’t-ever memoirist talk to her?

She chitchats, then says, “Your memoir sold.”

And I want to scream NO!

Not no as in I can’t believe it.

No as in don’t. I want to be the sad person. I’ve finally found an identity outside of books, any books, cookbooks, canonical ones, or otherwise. I didn’t write, read, or craft this me. I’m the publishing failure in a best-selling career. I’m nuanced. Textured. Better with wine. And given all the havoc I’ve caused in my life, the people I’ve hurt in my mad quest to find a version of me in some great work of literature, this me is probably what I deserve. And you can’t take that away from me.

I’ve finally found an identity outside of books, any books, cookbooks, canonical ones, or otherwise. I didn’t write, read, or craft this me. I’m the publishing failure in a best-selling career.

She’s not. She’s talking numbers, contracts. She names a small art press. “This is the best we could hope for. Your book would be lost at a big New York house. This is what you wanted.”

No, it’s not. Who will I be, if I’m not the guy who wrote a book that never sold?

I’d struggled through a four-and-a-half-year process to arrive at a me who’d merged his voice with his story. A true me, which I then chucked the moment I found a ready-made one. Tossing it out even felt like reading a great book. You look up and think, Wait, where am I? Then you go back to this story that’s handed to you. Which is how I felt everyday of my adopted life anyway. I’d settled for a voice that sounded like mine but wasn’t because I thought it was more understandable, better, just all around more satisfying than the voice I kept trying to craft for all those years.

I’d also fallen into the persistent lie that we can gain a voice, a self, that we can become who we are—and then that’s that, the end. Ta da. Except that’s not how voice works. Much less the self. You don’t find yourself and stop. A true self is a process, not a product. A true voice is a constant search for the right pitch. Even trained singers have to warm up.

I’d worked for years to tell an authentic me. Then I threw it away because I first mistook sellable for sayable, and then because I found something easier than the mind-torquing work it takes to speak my own self in the words I love. I became who people thought I was, who I thought I was: the failed writer in a publishing career. I’d found a way to the voice of the guy who still wants to fuck William Faulkner in Julia Child’s kitchen, then tossed out that self because I was too chicken to go on living it in my body. I fought to find me, then tried to take the easy way out. Which is exactly how not to write a memoir.

_________________________________________________________________

Mark Scarbrough’s Bookmarked: How the Great Works of Western Literature F*cked Up My Life is available now via

Propertius Press.

Mark Scarbrough

Mark Scarbrough has published 35 cookbooks with his husband, Bruce Weinstein. Bookmarked is the first time he has told his own story through memoir. Scarbrough hosts three successful podcasts, Walking with Dante, the only podcast to slow-walk Dante’s Comedy and Lyric Life, a podcast devoted to the pleasures of lyric poetry. With Bruce Weinstein, he hosts a popular food podcast, Cooking With Bruce and Mark. He also teaches eight-week seminars on Virginia Wolf, William Faulkner, and Toni Morrison and leads an international book group of more than 150 committed readers who work through challenging fiction while zoom-sipping wine. Mark has been featured on outlets like TODAY- NBC, The View, Good Morning, America, NPR’s Morning Edition, Fox and Friends, and The Martha Stewart Show. For more information visit www.markscarbrough.com and connect with him on Instagram and Facebook.