On Family Tragedy, Joan Didion’s Parties, and Storytelling: Griffin Dunne on His Debut Memoir

Lisa Liebman Talks to the Actor, Producer, and Director

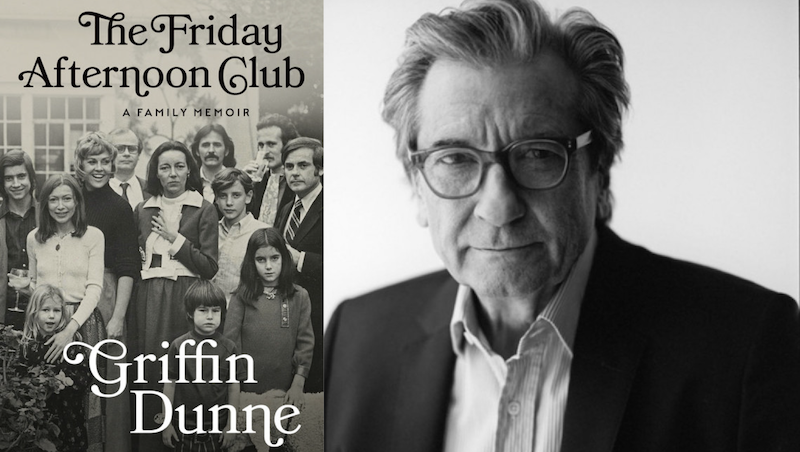

Griffin Dunne never intended for his debut memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club, to be a celebrity tell-all. The actor, producer, and director had only the book’s subtitle—A Family Memoir—in mind when he began refining some of the personal stories he had regaled friends with, and jotted down over the years. (Credit the title—which refers to weekly meet-ups Dunne’s sister, Dominique, had with acting pals in the backyard of their mother’s Beverly Hills home—to his editor John Burnham Schwartz.) “Writing a book was on my bucket list,” says Dunne about a goal that’s unsurprising given his literary lineage. His father was journalist and novelist Dominick Dunne; and his uncle and aunt were novelists and screenwriters John Gregory Dunne, and Joan Didion.

While the first-time author disregarded Didion’s aphorism that “a writer is always selling somebody out,” he was inspired by his relatives all writing “from such personal places.” The result is a disarming account of growing up the eldest son of Ellen Beatriz Griffin, the socialite daughter of a cattle rancher, who had Broadway aspirations, and his “social climber” dad, a TV and film producer who was hiding his homosexuality. Dunne describes the ways in which he was “a little con artist” during his, and his siblings’ charmed Hollywood childhoods. Later, as he carved out a life in New York City, his mother’s Multiple Sclerosis worsened; his father got sober; his brother, Alex, struggled with mental health issues—and Dominique was murdered by her ex-boyfriend.

Here, Dunne details some of the memoir-worthy moments from his early life.

*

Lisa Liebman: Your parents entertained a who’s who of Hollywood. Sean Connery saved you from drowning when you were eight. You caught Judy Garland rifling through the medicine cabinet. Warren Beatty once played the family piano to avoid a game of Charades. Still, you wanted a father like your “hothead uncle,” who struck you as “a fearless son of a bitch,” unaware that your own dad was a war hero. You lied about things big and small. A dyslexia diagnosis got you shipped off to boarding school to repeat the sixth grade, where you learned to cheat and steal. Was your behavior because you sensed your parents were hiding that your dad was gay?

Griffin Dunne: I think so. They were very loving toward us as children. But there was that secret that hung in the air, that we were too young to diagnose. When you are in a house of secrets, there’s a certain osmosis that takes place, [and it] kind of infected me. The sneaky behavior during my adolescence of just wanting to get away with something… and to tell stories about myself that weren’t true. As if my personality wasn’t enough, I had to embellish who I was.

LL: There was bad blood between the Dunne brothers after John’s success outshone Nick’s. It was exacerbated by your dad’s inability to repay a loan, and after John and Joan took their daughter Quintana to Paris to avoid testifying at John Sweeney’s murder trial. How did growing up around all of that ambition and competition affect you and your siblings?

GD: I didn’t appreciate the extraordinary people that came to my house when I was young. I would be introduced to filmmakers—Billy Wilder, George Stevens, and John Huston—whose films I would later study. But at the time, it escaped me. From a very early age, John and Joan invited me to their parties. I write about the one that they gave for Tom Wolfe, when he was in Los Angeles for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. How Janis Joplin was going to attend, and I never got to meet her [because his mother took him home]. I ended up making a short film about that, and it got nominated for an Academy Award—my very first directing assignment. No matter what was going on with my father, John and Joan continued to always have me at their homes.

LL: You arrived in Manhattan to study acting as a divorced, 19-year-old high-school dropout. You worked as a waiter, and sold popcorn at Radio City Music Hall while dallying with Rockettes, and trying to get acting jobs. You write you found your privilege embarrassing and “inexplicably shameful.” Why not embrace your nepo-baby status? Were you trying to get out from under the shadow of your famous family?

GD: Most definitely. Being from Beverly Hills—it’s such a famous place. It just struck me as a ridiculous town where celebrity was the most valued commodity. Coming to New York to be in theater, not in movies—as it turned out, I ended up in movies. But my idea was to get away from Hollywood and be a New York actor. I had such a strong impression of what that was from Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, and Dustin Hoffman. I wanted to create my own narrative, my own story.

I didn’t appreciate the extraordinary people that came to my house when I was young. I would be introduced to filmmakers—Billy Wilder, George Stevens, and John Huston—whose films I would later study. But at the time, it escaped me.LL: You had successful and not-so successful encounters with writers. You and your film producing partners showed up on Ann Beattie’s doorstep to see about optioning the movie rights to Chilly Scenes of Winter, and she was welcoming. But while bartending a private dinner party, you were groped by both Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote. It was only after the hostess spoke up, telling Williams that you were Joan’s nephew, that the embarrassed writer invited you to sit down. What was Joan’s reaction to that story?

GD: She laughed her ass off. She just thought it was hilarious. She had a very strong connection to Tennessee—not socially, just aesthetically. She found his writing and his charm and his tragic persona very touching. It went both ways; they had this correspondence that was very warm and loving and grateful. It wasn’t a constant thing. They were mostly notes that are in the New York Public Library being archived right now. Joan collected flowers in Malibu Canyon, and crushed or pressed them behind lucite, adding little drawings, and noting what the plants were. She sent one to Tennessee, and a lovely note came back.

LL: Carrie Fisher was your confidante, and your relationship was platonic—except for the night she lost her virginity to you. When she went to London to film what she thought was an inconsequential sci-fi film, her co-star, Harrison Ford, was the guy you had hung out with while he built a deck for John and Joan. You write that Carrie’s Star Wars stardom left you feeling as if you were no longer on equal footing. But good reviews in an Off-Broadway play “brought the glow back” to your friendship. You didn’t write much more about your life-long relationship. Was it because Carrie’s daughter, actress Billie Lourd, wasn’t happy with Todd Fisher’s book?

GD: No, I just felt like I covered the part that was the most vivid. As we got older, we lived on opposite sides of the country, and we were still very, very close. But she also had dozens and dozens of other people that she was just as close with. Those years in New York, during our one-on-one friendship, was as far as I wanted to go.

LL: After starring in and co-producing Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, you were a hot property, despite the film’s mixed reviews. You made bad choices, in part due to booze and blow. You write: “With stardom in my sights, I worked like a mad scientist concocting formulas for how to best fuck it up,” acknowledging that Dominque’s death also affected your decision-making. Any regrets?

GD: I certainly went through a period of regret, and a lot of self-punishment. I shunned the heat that came to go behind the camera, and lost all momentum. But when I finished writing the book, I took an assessment of my life and career, and I really embraced the variety of choices I’ve made. How much I learned about filmmaking that I might not have, if I was solely focused on being an actor. I was able to create projects, and work with [directors] Sidney Lumet, John Sayles, and Lasse Hallström, and see how they worked. So I don’t regret any of it.

LL: You save the story of your sister’s murder at age 22, and the subsequent trial for the second half of the book. Was that the hardest thing to write?

GD: As I wrote in the acknowledgments, my brother said, “Write whatever you want about me, just have it come from a place of love.” That was the best direction I had, and carried me through writing about my family. Dominique was the pulse of the book for me. I didn’t know I would spend so much time writing about the trial until I got there. But her—I don’t know—her spirit, her humor, her smile. It just all came back. It was so vivid, and I really enjoyed her company.

[During the trial] we were all in a place of dark magical thinking. No one was thinking rationally. My father’s rage [was] almost stronger toward the defense lawyer than it was toward the killer. And my mother would sometimes withdraw, and go into the world of whatever mundane crap was on television to escape. We were in a relentless fog of fear, having no control over our futures.

LL: Writing about the trial for Vanity Fair brought your dad success as a true-crime writer. Though happy for him, you also felt his writing was “an invasion of our family’s memory,” and that “his sharing our sorrow with the world distasteful.” But you ultimately came to think of the article as “a bible,” and shared it with anyone who might become part of your life. Is that still true?

GD: Very much so. So many things that I didn’t appreciate or disliked, I came to realize the importance of later. I used to make fun of my father for keeping leather-bound scrapbooks with celebrity photos. I thought they were kind of ridiculous. Now I think they’re an incredible documentation of a period of social history in early ’60s Hollywood. That article was so personal and captured what we were going through so accurately, that it was like reliving it to read it. I remember acting in a movie, and seeing a crew member reading it, and I felt terribly exposed. As years went by, I realized what an incredible piece of writing it was. That at great cost, my father had truly found his voice, and his point of view as a journalist.