On E.M. Forster’s Maurice and the Urgency of Expanding Queer Genealogies

William di Canzio on the Personal and Literary Inspirations

Behind His Novel

My parents’ learning that I’m gay triggered a family trauma. I did not come out to them. Rather, they confronted me with the “evidence” of a phone bill. After a late-night scene of tears, insults, reproaches, and rage worse than anything I had imagined, they implored, then insisted, that I see a psychiatrist to be “cured.” My father, a gentle, mild-mannered man, very proud of me, suggested that I change my name to spare him a family scandal.

My parents, who, trust me, were excellent people, died many years ago, having long since repented their bigotry. They loved me, and love eventually prevailed. (The psychiatrist gave up on me after one visit; and no, I did not change my name.)

This painful episode preceded, by only a few months, the momentous announcement from the American Psychiatric Association that removed homosexuality from its roster of psychiatric disorders—December 15, 1973. With the passage of time, I’ve come to understand how not only I but also my parents were victims of a socially and religiously sanctioned lie. They were told that their only son, whom they loved immeasurably—healthy, bright, well-behaved, praised by his teachers—was fundamentally, and in the most shameful way, “sick.”

Hence, the importance to me of E.M. Forster’s great novel, Maurice. The hero, like me, was a young person who had been lied to, told a lie even more heinous than the one forced on me: not only was his sexuality depraved and sinful, but also a crime. Conventional, beloved, well-off, well-educated Maurice is made to struggle with self-hatred, condemning himself as “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort”; he visits not a psychiatrist but a hypnotist in the hope of being “cured.” And yet, in Maurice, truth triumphs. By the end of the novel, Maurice has accepted himself and his love for Alec. I had never read such a story.

With the passage of time, I’ve come to understand how not only I but also my parents were victims of a socially and religiously sanctioned lie.

Maurice was first written in 1913-14. Revised over decades, it nonetheless remained unpublished until 1971. For most of that time, until the Sexual Offenses Act became English law in 1967, sexual expression between men was a crime in Forster’s homeland. His famous note on the manuscript reads, “Publishable, but is it worth it?” Worth the censorship, the hubbub, contempt, condescension? Worth risking the dismissal by critics and readers of a lifetime’s brilliant work? It was only through the efforts of Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden, younger friends who recognized the virtue and value of the novel, that Maurice was published the year after Forster’s death at the age of 91, just two years before the APA’s announcement of the scientific truth.

*

Why did I write Alec? Why spend five years writing a novel that, because of copyright, I was uncertain I would be permitted to publish, even if I could interest a publisher? Because of my instinct there was more of the story to tell.

I saw Maurice anew after reading Wendy Moffat’s beautiful biography of Forster, A Great Unrecorded History. Learning more about the man’s life confirmed my instinct. He had tried to write an epilogue about the lovers’ future together, away from London, sharing their lives in seclusion as “woodsmen,” but he threw it out. The Great War had so changed the world where gamekeeper and gentleman had met—destroyed it, really—that Forster was stymied in his efforts to imagine a life for them. But with the 20th century well behind us, I believed I could imagine what happened to them while remaining true to Forster’s vision.

I also confess to the immodest conviction that I know Alec Scudder better than Forster did. He certainly knew Maurice Hall, a London gentleman of means, educated at King’s College, Cambridge, like Forster himself—someone he might have met at school or dined with. But Alec is the son of a village butcher, a servant, one tasked with easing but not otherwise participating in the lives of his self-styled “betters,” anticipating their wants, watching but never judging those who pay him. Once I saw Alec not as a human prop, but as a kid from a blue-collar family who had found a certain job, I felt closer to him. I understood his need to work and his yearning to quit, as he does in Forster’s novel, not because he disliked being a gamekeeper, but because it imposed on him the demeaning label of servant. Quit the job, quit England, and try his luck abroad.

We see the seeds of that courage in Forster’s novel. In mine, we watch it mature in Alec’s love for Maurice and through the ordeal of the Great War.

In Maurice Hall, Forster set out to present a hero different from himself: a handsome, athletic man of the world, a conformist (in all ways but one), and by no means overburdened with cleverness. In Alec Scudder, I also discovered a hero different from myself. It’s a difference that has to do more with spirit than with looks or intellect. I spared Alec the debilitating scrupulosity of being the child of a devout Catholic family sent to religious schools. Instead of confusion, he is blessed with clarity about his nature from an early age; instead of self-doubt, with self-acceptance and confidence. From these qualities emerges the courage, moral and physical, that he lives by. We see the seeds of that courage in Forster’s novel. In mine, we watch it mature in Alec’s love for Maurice and through the ordeal of the Great War.

*

Alec is my passionate response to Maurice, a seminal work of art. It is also a gesture of reverence to heritage and genealogy. “A great unrecorded history” was Forster’s phrase for the lives, sufferings, and achievements of queer people: our essential role in humanity. We are largely ignored in “master narratives” of the past, uncredited, our sexuality condemned, ignored, or obliterated. Maurice is a priceless, pioneering artifact of that unrecorded history. The story of its publication, half a century ago this year, is now among its annals.

Forster modeled the love of Maurice and Alec on that of his friends Edward Carpenter and George Merrill. These are names we all should know, because our genealogy is traced not in family trees but in networks of friendship and love. Carpenter knew Walt Whitman; Whitman, Oscar Wilde; Forster knew Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Benjamin Britten, Paul Cadmus; and so on. Alec is my own contribution to this inheritance, an imaginary recording of a passage in that heroic history.

__________________________________________

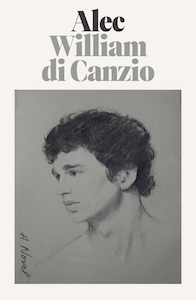

William di Canzio’s Alec is available now via FSG.

William di Canzio

William di Canzio’s plays—including the award-winning Dooley and Johnny Has Gone for a Soldier—have been staged in New York, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Philadelphia; at Yale University and the O’Neill Theater Center; and at the National Constitution Center. Di Canzio has taught literature and writing at Smith College, Haverford College, and Yale University. Since 2013, he has taught in the Pennoni Honors College of Drexel University.