On Domesticity and Memory in James Baldwin and Becky Suss

Peter L’Official on Suss’s “Brand of Children’s Vision for Adults”

In 1976, James Baldwin published his first and only children’s book, Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood—a collaboration with French artist and illustrator Yoran Cazac. Described on its jacket cover as a “child’s story for adults,” the book drew on Baldwin’s own difficult experiences growing up as a Black boy in Harlem, though it was written partly at the request of another young, Black, New York City “little man.” Baldwin’s nephew, Tejan, would often ask his famous uncle when he would ever write a book about him, to which Baldwin responded in the form of the story’s four-year-old protagonist, TJ. The book, however, was not well-received upon publication.

The Black American scholar and children’s book writer, Julius Lester, found its hybrid perspective “unclear,” and deemed the book “slight” and “not especially exciting” in a review for The New York Times. Children’s literature was a “genre unto itself” and required, in Lester’s estimation, its own prescribed vision. Any Baldwin-esque “literary figures” moonlighting in adopted genres who wished to write a “story of childhood for adults” should do that, according to Lester, but rather in the form of an adult novel—something akin to Baldwin’s own first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. [1]

Little Man, Little Man quickly fell out of favor, and out of print, until it was recently resurrected in 2018 by Baldwin’s niece and nephew, Aisha Karefa-Smart, the aforementioned Tejan Karefa-Smart, and the scholars Nicholas Boggs and Jennifer Devere-Brody. [2] A tale featuring three Harlem children—TJ, WT, and Blinky—that is told both in a Black vernacular and a buoyant, searching child’s voice that knows better than to subscribe to the fiction of American innocence, Little Man, Little Man is compelling because it condescends to no one—child or adult alike.

Baldwin had the audacity to invest his young, Black characters with a perception and perspective that had already internalized the vexed realities of poverty, police brutality, addiction, and racism which, in 1970s Harlem, one didn’t have to look far or wide to see. In this way, Baldwin’s singular children’s book offers less in terms of a digestible, narrative-based lesson—as Lester might have preferred—to answer perhaps a higher calling. Instead, we might read Little Man, Little Man as a tool that can be used not merely to highlight narratives—and persons—that have been marginalized or ignored entirely, but also one that illustrates how we might reshape our own vision to see the world, both as a child and as an adult, through its complex, compound image. [3]

As products of meticulous research, memory, editing, and imagination, they are as much poems as they are paintings.

It is this arresting synthesis of visions that I think of whenever I stand in front of the work of Becky Suss. Her work asks us to see differently, or rather, more accurately, if we admit to ourselves that our adult recollections of places, spaces, and objects are often just as subject to the distortions and exaggerations of memory in which our children often delight. Memories can be both vivid and furtive, lucid and surreal, distant and present.

Suss’s work imagines space for such dualities to appear at once, perhaps each adjacent to or one overlaid by the next. Her exacting, acute manner of rendering interior spaces and objects beguiles because her paintings seem to offer the fantasy that our recall—of a book, a framed silk Mughal print, or a welcoming vestibule—could ever be so precise. Yet, their scale, perspective, and mode of composition—with certain accoutrements mined from various sources—complicate that precision, and conjure within each painting curious, enchanting asymmetricalities. As products of meticulous research, memory, editing, and imagination, they are as much poems as they are paintings. If Baldwin’s book crystallized the notion of a “child’s story for adults,” then we might think of Suss’s work as a brand of children’s vision for adults.

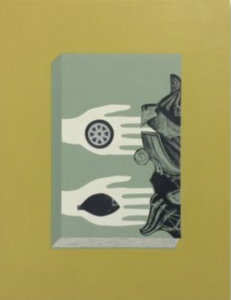

Becky Suss, “8 Greenwood Place” (1988-93), 2021 oil on canvas, 72 x 84 x 2 1/2 inches.

Becky Suss, “8 Greenwood Place” (1988-93), 2021 oil on canvas, 72 x 84 x 2 1/2 inches.

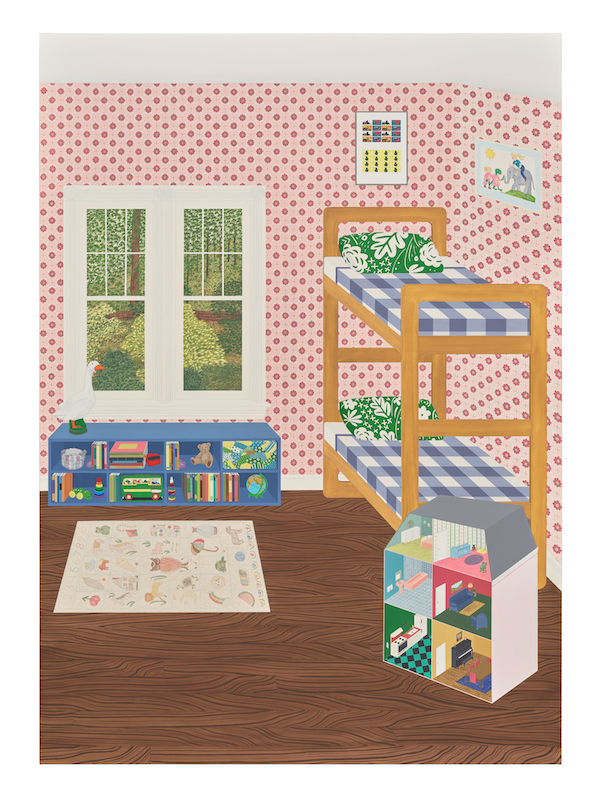

Becky Suss, “8 Greenwood Place (my bedroom),” 2020 oil on canvas, 84 x 60 x 2 1/2 inches (canvas).

Becky Suss, “8 Greenwood Place (my bedroom),” 2020 oil on canvas, 84 x 60 x 2 1/2 inches (canvas).

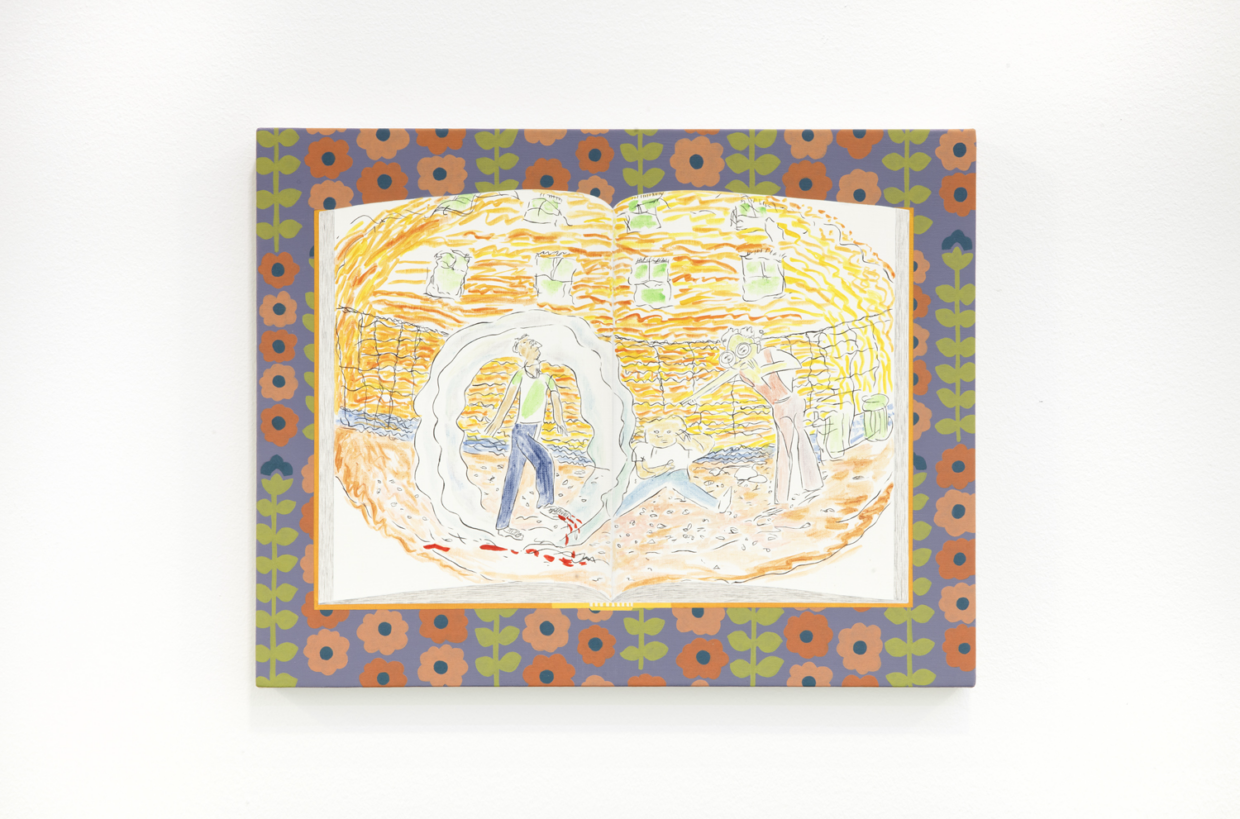

It is no wonder, then, that Suss painted an illustrated excerpt from Little Man, Little Man. Her WT, TJ and Blinky (2020) depicts a single scene from Baldwin and Cazac’s collaboration, where the three children process an injury to WT—a cut and bleeding foot, due to some recently shattered glass—before all retreat to their building’s superintendent’s basement apartment for treatment. It is, in a book that has already considered what crime, surveillance, drug dependence, and other more subtle forms of violence might look like to children, the grisliest moment of Baldwin’s narrative.

Cazac’s illustration, with no accompanying text to distract from its frenetic, colorful depiction of shock and confusion at the bloody footprints on the sidewalk, is one of the few double-page spreads in the book. Suss displays it as such: the book is splayed open to that climactic page, and the jagged, intense energies of Cazac’s watercolor images are juxtaposed against the softer, childlike renderings of flowers and plants that suggest a vintage tablecloth upon which the book sits, waiting for a reader. Yet the image, in Suss’s hands, loses none of its power.

Be they child or adult, the artist has anticipated the viewer’s encounter with the painting in the space of the gallery, and recreated for them the act of discovery that occurs upon turning the page of any illustrated text. Suss trusts her viewers, especially the youngest among them, with the maturity to process this moment. And for the depicted characters, WT, TJ, and Blinky, it is their outside brought inside—a moment of emotional and physical exposure given shelter, as happens soon after in the narrative. The painting illustrates at once the uncommon appeal of Baldwin’s book, as well as the composite vision that Suss’s work possesses, and seeks to invest in us.

Becky Suss. WT, TJ, and Blinky, 2020. Oil on canvas, 14 1/8 x 18 x 1 1/8 inches, Inventory #BS20.015

Becky Suss. WT, TJ, and Blinky, 2020. Oil on canvas, 14 1/8 x 18 x 1 1/8 inches, Inventory #BS20.015

James Baldwin dedicated Little Man, Little Man to the queer Black painter Beauford Delaney, a mutual friend of Baldwin and Cazac, and an influential mentor to Baldwin in his youth. Of Delaney’s essential importance to him, Baldwin wrote: “I learned about light from Beauford Delaney, the light contained in every thing, in every surface, in every face. Many years ago, in poverty and uncertainty, Beauford and I would walk together through the streets of New York City.

He was then, and is now, working all the time, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he is seeing all the time; and the reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see.” [4] In an age of video meetings, remote learning, and endless streams of easily accessible images, our interior spaces—and ourselves—have never been on such constant display. But are we truly seeing amidst all this looking?

Suss, already prescient in her focus on domestic space and the objects within—which, of course, reflect our emotional interiors as well—dares to suggest that the finely-appointed households in her work do not require design training or an art historical background to appreciate. Young or old, they are made ours to behold. The heightened qualities of sight that have produced Becky Suss’s artwork aim to produce within us similar insurgencies of vision, as Delaney did for Baldwin—we can’t, nor should we, want to see the same way again.

*

[1] Julius Lester, “Little Man, Little Man,” The New York Times Book Review, September 4, 1977: 22.

[2] James Baldwin, Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

[3] Nicholas Boggs, “Baldwin and Yoran Cazac’s ‘Child’s Story for Adults,’” in The Cambridge Companion to James Baldwin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 118–32.

[4] James Baldwin, “Introduction to Exhibition of Beauford Delaney Opening December 4, 1964 at the Gallery Lambert,” in Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 1978), unnumbered page.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Becky Suss, available via Skira. Top image credit: Becky Suss, 8 Greenwood Place (1997-99), 2022 oil on canvas, 72 x 84 x 1 1/2 inches.

Suss’ exhibition Greenwood Place is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery through June 18.

Pete L’Official

Peter L’Official is an Associate Professor of Literature and Director of the American and Indigenous Studies Program at Bard College. His first book, Urban Legends: the South Bronx in Representation and Ruin, was published by Harvard University Press, and his next project will explore the intersections of literature, architecture, and blackness in America.