On Dickens’ Demons and Weird Relationship with Christmas

A Close Reading of A Christmas Carol

There was certainly plenty to cause Charles Dickens dismay as he started to plan the Carol in 1843. He had recently visited a ragged school, established in a dilapidated house in the swarming slums of Saffson Hill (the precise location, he later claimed, of Fagin’s den in Oliver Twist), and had been appalled by what he found: “a sickening atmosphere, in the midst of taint and dirt and pestilence: with all the deadly sins let loose, howling and shrieking at the doors.” “I have very seldom seen,” Dickens told the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, “in all the strange and dreadful things I have seen in London and elsewhere, anything so shocking as the dire neglect of soul and body exhibited in these children.”

Many of them earned a living through thieving or prostitution; others crept away at night to shelter “under the dry arches of bridges and viaducts; under porticoes; sheds and carts; to outhouses; in sawpits; on staircases”; all were steeped in misery and squalor. But who or what could rescue these pitiful creatures from the “profound ignorance and perfect barbarism” into which they had been born? And how could Dickens’s middle-class readers be brought to realize that Ignorance and Want—the “meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish” children who appear to Scrooge from beneath the robe of the Ghost of Christmas Present—were as much their responsibility as their own more pampered offspring?

These were among the questions that Dickens returned to in a speech three weeks later at the Manchester Athenaeum, in which he again underlined the need for education to drive away ignorance, “the most prolific parent of misery and crime,” and ended with an appeal for workers and employers to come together in recognition of their “mutual duty and responsibility.” And so the public themes of A Christmas Carol started to fit together in Dickens’s mind: education; charity; home.

There were also more private impulses at work. Sales of Martin Chuzzlewit, the novel in which he had set out to explore “the number and variety of humor and vices that have their roots in selfishness,” had started to flag. Dickens’s decision to send his “hero,” Martin Chuzzlewit, off to America half-way through the serialization had done little to increase his popularity, and Dickens’s publishers had started murmuring about a contractual clause that permitted them to subtract money from his income if the novel’s sales did not meet the expectations set up by his handsome advance. A career that had been flourishing a year or two previously was threatening to unravel before his eyes. Nor was his private life in much better shape. His wife Catherine was expecting another child, and although it would be unfair to think that she was solely responsible for this state of affairs, the prospect of another mouth to feed cast Dickens into a state of mind that alternated between gloom and fury, saddled with “a Donkey” of a wife and a father who insisted on cadging money off anyone who wanted to keep on good terms with his famous son. At one point, Dickens confessed, he dreamed of a baby being skewered on a toasting-fork: hardly the dream of a man looking forward to an extra mouth to feed. (Not that it embarrassed Dickens into keeping it to himself: this was also the dream in which “a private gentleman and a particular friend” is announced to be “as dead Sir . . . as a doornail,” so providing him with one of the opening sentences of his new book: “Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”) Even by his own standards he was restless and dissatisfied, involved in so many parallel careers—novelist, journalist, public speaker, social campaigner, and more—that his life seemed to be turning into a perpetual fidget.

At the same time, his body had started to give out the first warning signals that it was not as keen as his mind to be involved in so much at once, with the appearance of intermittent facial spasms which he put down to “rheumatism,” but which seem just as likely to have been an angry nervous tic. And all the while there were the voices in his head: the characters who, he said, clustered around his desk as he wrote, clamoring for his attention, like ghosts who could only be laid to rest once they had been set down on the page. “I seem to hear the people talking again,” he told a French journalist at the time. By this he seems to have meant primarily that his head was still echoing with the voices of the people he had met on his recent trip to America, but it is hard to be sure, not least because Dickens himself did not always seem to know whether his characters were believable because they had been copied from life, or because the world was becoming as grotesque and fantastical as one of his stories. What does seem clear is that, given his recent sales figures, he would have been forgiven for wondering whether he had misheard what they had to say for themselves.

Dickens himself did not always seem to know whether his characters were believable because they had been copied from life, or because the world was becoming as grotesque and fantastical as one of his stories.

One word that looms up out of the first paragraph of the Carol is the capitalized “Change”: “Scrooge’s name was good upon ’Change for anything he chose to put his hand to.” Here “Change” is short-hand for the Exchange, the center of London’s financial market in which Scrooge makes his money, but if Scrooge is “good” for anything he puts his hand to, then what of other professions that involve putting one’s name to bits of paper? What are writers good for? What is their business in life? Not easy questions to answer, especially by a writer who seemed unsure where his career was heading.

And so he went back. Back to the cheerful tone of his biggest commercial success, The Pickwick Papers, from which he borrowed the interpolated tale of the gravedigger Gabriel Grub, “an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow—a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself,” converted by some mischievous goblins who show him visions of the past and future. Back to the thundering voice of Carlyle, with Scrooge’s thin-lipped response to the men collecting charitable donations (“Are there no prisons? . . . And the Union workhouses? . . . The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigor, then?”) replaying and replying to Carlyle’s sarcastic question in Chartism (1840): “Are there not treadmills, gibbets; even hospitals, poor-rates, New-Poor Laws?” (pp. 13–14). Back to the world of the pantomime, Dickens’s first and most lasting theatrical love, in which a Benevolent Spirit would magically transform the characters or their setting, creating a fairy-tale world in which, as Dickens recalled in “A Christmas Tree” (1850), “Everything is capable, with the greatest ease, of being changed into Anything, and ‘Nothing is, but thinking makes it so.’”

Finally, back to the money-grubbing world of Martin Chuzzlewit, which Dickens was completing at the same time he was working on the Carol, and which had made him realize that there were more subtle ways of sending people abroad than merely packing them off to America. As Marley explains, “It is required of every man . . . that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellowmen, and travel far and wide”—a form of self-projection one might expect writers to be especially skilled at, as the narrator of the Carol claims to be “standing in the spirit at your elbow,” but also one that Dickens wanted to show was at the heart of all the other ways in which one person might affect another “for good” (pp. 22, 28).

As he set to work on the Carol, Forster records with what “a strange mastery it seized him,” laughing and crying aloud as he wrote, sending himself abroad with each movement of his hand across the page. And then, once he had finished his work for the day, he would be off, pacing the city streets through the night, sometimes covering ten or fifteen miles at a time. Perhaps he was attempting to wind himself ever tighter in the coils of the city. Perhaps he was attempting to pick up enough speed to escape its gravitational pull. All that can be said for certain is that motion and emotion were curiously tangled together in Dickens’s mind, and that if at the start of the Carol Scrooge is something of a self-parody of Dickens’s fears about himself—the solitariness, the unhappy childhood, the desire for money—by the end Dickens had successfully brought him into line with a far more optimistic view of himself, as he bursts out into the street ready to send himself abroad imaginatively as well as physically, as light-hearted as he is light-footed.

The Carol took Dickens a little over six weeks to complete, and he wrote the final pages at the beginning of December, following it with “The End” and three emphatic double underlinings.

Then, he said, he “broke out like a Madman”: a whirl of parties, conjuring performances and dancing, as if he secretly worried that there would be something unhealthily Scrooge-like about staying in one place for too long during the festive season. The book itself needed to be ready in time for the Christmas market, and Dickens kept his customary sharp eye on every aspect of its production. Priced at a relatively modest five shillings, it was handsomely (and seasonally) bound in red cloth, with gilt-edged pages, four hand-colored etchings provided by John Leech, and four additional black and white wood engravings. Dickens had chosen to publish the book at his own expense, hoping that he would make more money by receiving a percentage of the profits than he would by accepting a one-off payment, and his anxiety is clear in the strained mood of self-congratulation that starts to appear in his letters: the Carol was a modern fairy-tale that would drive out “the dragon of ignorance from its hearth”; it was a “Sledge hammer” that would “come down with twenty times the force—twenty thousand times the force.” Financially, Dickens’s nervousness was well founded: although the Carol had sold some 6,000 copies by Christmas Eve, and kept on selling well into the New Year, the high cost of production meant that he received less than a quarter of the profits he had been expecting. In every other way, though, the publication was an unprecedented success.

The critics were almost uniformly kind. One or two murmured that Dickens’s genial tone was maybe a little overbearing, his hospitality a little suffocating—a view later echoed by G. K. Chesterton, who noted that Dickens “tended sometimes to pile up the cushions until none of the characters could move”—but otherwise the reviews were full of praise for his skill in producing a conversion story that was also squarely aimed at changing the hearts and minds of its readers. Francis Jeffrey applauded the Carol’s “genuine goodness”; the usually sharp-tongued Theodore Martin argued that it was “finely felt, and calculated to work much social good”; Thackeray described it with envy-tinged admiration as “a national benefit, and to every man and woman who reads it a personal kindness”; even Margaret Oliphant, who came up with the faintest praise of all, later characterizing Dickens’s book as “the apotheosis of turkey and plum pudding,” admitted that “it moved us all in those days as if it had been a new gospel.”

“Dickens’ Christmas Carol helps the poultry business amazingly … Everybody who reads it and who has money immediately rushes off and buys a turkey for the poor.”

Many of the ways in which the Carol moved its readers have since passed into critical folklore. Jane Welsh Carlyle reported that “visions of Scrooge” had so worked on her husband’s “nervous organization” that “he has been seized with a perfect convulsion of hospitality, and had actually insisted on improvising two dinner parties.” A Mr. Fairbanks, who attended a Christmas Eve reading of the Carol in Boston in 1867, was so moved that thereafter he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every worker a turkey. “Dickens’ Christmas Carol helps the poultry business amazingly,” as one wag noted in Wilkes’s Spirit of the Times (December 21, 1867). “Everybody who reads it and who has money immediately rushes off and buys a turkey for the poor.” Wherever one looks in the period, in fact, there are examples of the Carol being read as a good book that also did much good. Nor were its practical effects only of the charitable kind. By the end of February 1844, there were eight rival theatrical productions of the Carol running simultaneously in London, while replies from other writers started to appear in print, including W. M. Swepstone’s Christmas Shadows (1850), Horatio Alger’s Job Warner’s Christmas (1863), and Louisa May Alcott’s A Christmas Dream, and How It Came True (1882), like a set of variations on the theme of redemption: some of them describing Scrooge’s new life as a reformed man, and others less charitably showing where, in the writer’s humble opinion, Dickens’s story needed to be put right.

Dickens himself seemed equally unable to leave his story alone, periodically returning to it during the rest of his career to tweak the phrasing or fiddle with the punctuation. But perhaps this is not surprising when one considers the central place that Christmas occupied in his career. From his early short essay “A Christmas Dinner” in Sketches by Boz (1836) to his incomplete final novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), in which an uncle appears to have murdered his nephew on Christmas Day, Christmas is sunk into his imagination like a watermark. Year after year his mind would strike off in different directions; year after year he would return to the same imaginative centre, as Christmas exerted its gravitational pull. “We all come home, or ought to come home, for a short holiday,” he writes in “A Christmas Tree,” and the scattered evidence of his stories suggests that Christmas provided him with something similar in his writing: a short holiday from the relentless grind of producing monthly installments of the latest novel; a return to his imaginative roots; a home-key. “Christmas was always a time which in our home was looked forward to with eagerness and delight,” his daughter Mamie recalled, while his son Henry agreed that Christmas in the Dickens household “was a great time, a really jovial time, and my father was always at his best, a splendid host, bright and jolly as a boy and throwing his heart and soul into everything that was going on.”

However rosy these recollections, others observed that Dickens’s enjoyment of Christmas seemed more determined, even ruthless, than one might expect from someone with a genuinely boyish sense of fun: whether he was learning a new conjuring trick, or mastering the steps to a dance, his son Charles noted, there was always the same “alarming thoroughness with which he always threw himself into everything he had occasion to take up.” If Christmas was a time for returning to the world of childhood, it was also a time for asserting control over it, measuring how far he had traveled from a period that he tended to look back on with the same self-pity that stirs Scrooge when he encounters his younger self: “a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge . . . wept to see his poor forgotten self as he used to be” (p. 31).

![]()

From A Christmas Carol and Other Stories by Charles Dickens, edited by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. Copyright © 2018 by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

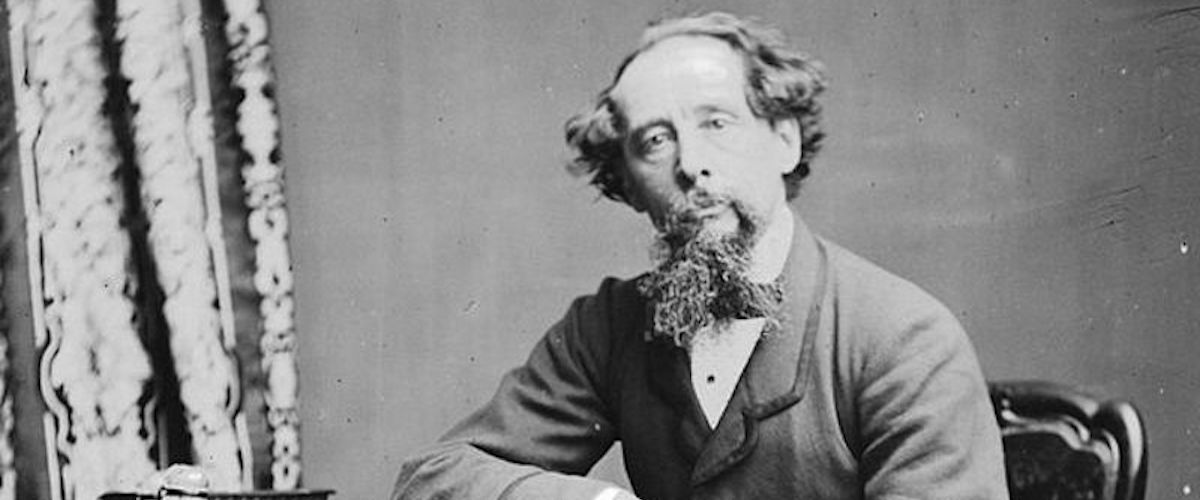

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst is the editor of Christmas Carol and Other Stories by Charles Dickens, author of Becoming Dickens (Harvard UP, 2011), winner of the 2011 Duff Cooper Prize, and has edited editions of Dickens's Great Expectations, Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, and Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies for Oxford World's Classics. He writes regularly for publications including the Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, TLS, and New Statesman.