On Debbie D, One of Hip-Hop's Legendary Pioneers

Kathy Iandoli Reflects on the Women Who Succeeded in a Male-Dominated Music Scene

I’m seated in a booth at a steakhouse in New Jersey with Harlem-born, South Bronx–bred, hip-hop pioneer Debora Hooper, known as “Debbie D.” Now a preacher and ministry coach, Debbie is referred to as a hip-hop matriarch, one of the treasured few female pioneers to arrive during hip-hop’s genesis.

She lays before me one of the only real hip-hop informational artifacts of the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s a binder-bound collection of flyers. They’re amateur in design, when compared to the loud, glossy ones that would become a hip-hop nightlife staple. The flyers are all packed with names scribbled across multicolored photocopy paper, separated in lists at times by groups and solo performers. Debbie’s name is listed quite often as a soloist, the only woman on the scene for a solid three years, at least judging from the flyers she has. Sometimes local high schools were listed, letting the kids know which of their friends had been invited to attend. It’s a subtle testament to just how young this art form and its participants truly were at its inception.

“If your group name was on the flyer, then you weren’t a soloist yet,” Debbie explains. “A soloist performs alone onstage with her DJ. The proof is in the flyers.” Debbie D was one of the first to break from her group DJ Patty Duke & the Jazzy 5 MCs. She added DJ Wanda Dee to her setup and started performing solo in late 1981.

If you scan the webpages and social media sites of women from that era, many refer to themselves as “the first” female MC soloist. It’s a footnote that at face value feels like a moot point, but for so many women, it’s a necessary detail to secure their supremacy in hip-hop’s tangled history. The qualification for some is having a physical recording; for others, it’s the number of times they were billed on flyers by themselves (with no crew attached), yet many lay claim to that spot as the first female soloist.

“Actually, none of them were first,” DJ Cutmaster Cool V tells me. Cool V was Biz Markie’s DJ and producer for over three decades. “What we’re getting caught up in now is first and last. All of these girls are relevant because they came out at a time when it was hard for girls to come out.” Perhaps they all arrived at once and never knew each other. He references Virginia’s Golden Gate Quartet, a group founded in the 1930s whose cadence was nearly identical to that of the Sugarhill Gang. They’re all men, though Cool V’s point was that maybe the music was being made, but not everyone was hearing it.

It’s kind of like the “tree falls in the forest” question. Maybe someone was “first” cultivating this same sound somewhere in Mississippi or Hawaii. Maybe it was a woman. Who really knows, and back then there wasn’t significant documentation to prove anything. This leads to a lot of history being rewritten in later years, since the only cards that can be pulled are word of mouth and those flyers. “You have to remember, everybody was young, they never went to different places,” Cool V adds.

The young hip-hop pioneers rarely ventured beyond the confines of their respective boroughs. It’s not like they were frequently traveling and experiencing the sounds of neighboring cities, states, or countries. First is subjective. “We’re older now, we can’t say ‘first’ or ‘last,'” he continues. “We can say ‘pioneer female MCs,’ from the importance of being at the top of the pioneering list, which is something essential for women from the Bronx.” Still, at that time, considering how hard it was for women to even have the opportunity to pick up the microphone, there’s an added layer of wanting to be cited as one of the scarce few who were actually offered an opportunity to flex their skills. The waiting game to get onstage was frustrating for women in hip-hop’s early days, though it wouldn’t last forever.

Now a preacher and ministry coach, Debbie D is referred to as a hip-hop matriarch, one of the treasured few female pioneers to arrive during hip-hop’s genesis.

In 1977, the block was hot in the South Bronx. Literally. A series of fires swept across New York City during the ’70s, decimating the Bronx especially. The blame has always been a mixed bag— from rumored arson to cashing in on insurance policies to the poor quality of the building structures and the negligence of the fire departments who came to the rescue once a blaze hit. Tensions were high, so when the infamous New York City blackout arrived in July ’77, widespread looting across the boroughs became the delayed response to everything else that was going on.

For the Bronx in particular, that looting was serendipitous for the expansion of hip- hop. DJ Kool Herc was one of the very few leaders of the burgeoning hip-hop movement to own a sound system. He’d had a solid four-year run as king since that infamous rec room party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, based largely upon his access to that boomin’ equipment. If your sound system was weak, you shouldn’t even bother showing up. Herc always showed up. During the blackout, young hip-hop kids looted, too, targeting electronics stores and boosting their own sound systems. While not everyone shoplifted their gear, that moment sparked a desire to DJ beyond the Bronx and into the neighboring boroughs. So now everyone got in on the action and threw their own parties. With countless jams happening that summer, there was plenty of room on the mic for women.

One pioneer in particular was Debbie D. Hailing from the Bronx’s Webster Houses, Debbie was one of the first female MCs to emerge during that historic summer of ’77. “I’ll never forget it, Kathy,” Debbie recalls to me, over four decades later. “I can see it plain as day. I was living in the projects, on the nineteenth floor, and I’m sitting on the bed. It’s warm outside, the windows are up, and I’m like, ‘What is that noise? What is that?’ I asked my mom if I could go outside, and I followed the music. I come to find out it was in this area called the Middle Building. There were like a million kids outside, thirteen, fourteen years old. There were no adults.” Parks were flooded with kids all congregating around one loud stereo system powered by a hookup to a street lamp. The DJ was spinning, the MC was rhyming. It was an open opportunity to strut your stuff, and right away Debbie D was all in.

After a few visits to the jams, Debbie posed a life-changing question to the DJ: Can I get on your mic?

“One of the major differences between old school and new school is that new-school hip-hop artists go straight into the studio,” Debbie remarks. “Old-school hip-hop artists went straight to the streets when it was time to rhyme. So what happened was, you had to prepare your rhyme and you had to say the same rhyme over and over in your house, because by the time you went to the street, you had to know it. You couldn’t mess it up.” It was trial and error leading to an art form that she would soon master, first joining the group DJ Patty Duke & the Jazzy 5 MCs and eventually bringing her skills to the silver screen in Harry Belafonte’s hip-hop flick Beat Street and aligning with the legendary Juice Crew, a cross- borough (though primarily Queensbridge-native) hip-hop collective founded by radio DJ Mr. Magic and producer Marley Marl.

There was a certain level of cachet to women joining all-male groups. First, it gave their presence a sense of purpose. For years, women were waiting for that fateful moment to jump on the mic in the midst of an already-forming male-dominated platform. Standing out from a mix of guys meant greater novelty, since back then, as an MC, male or female, you were merely an accessory to the DJ to begin with. “Now it’s all about the MC, but back then the DJ was at the forefront,” Debbie D says. As such, the best way to pop as an MC was to be different alongside your group-mates. Being an entirely different gender certainly helped, though skills were also crucial. Second, you had to join a crew no matter what. “Nobody was running around like a lone ranger,” Debbie adds. “Everybody was looking for a crew.” If your crew had a DJ with a strong sound system (back to the Herc business model), then you were guaranteed heightened visibility. If their system was weak, you had to work that much harder for recognition.

Crews were blooming left and right during that period, too, and women were becoming more popular as members, though only one woman per male crew could exist. Everything was moving fast. One of the first groups to incorporate a woman was the Funky 4, when it took on Sharon “Sha-Rock” Green. Eventually, MC Sha- Rock and fellow member Rahiem left the group, with Rahiem joining Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. The Funky 4 then recruited Li’l Rodney C! and Jazzy Jeff, but became the Funky 4 + 1 when Sha-Rock rejoined. “I was the original part of the four,” Sha-Rock confirmed in an interview with VICE in 2014. “There were three other guys and myself.” When she returned, she received the moniker “Miss Plus One,” and the group changed its name to the Funky 4 + 1.

“MC Sha-Rock was the most incredible MC,” Kurtis Blow says of Miss Plus One. “I would put her against any guy during that time. She was just devastating, and she was pretty too. She, to me, was the epitome of a female MC.” Funky 4 + 1 was the first hip- hop group to get a recording contract through Enjoy! Records with their 1979 single “Rappin’ & Rocking the House.” They later joined Sugar Hill Records under the leadership of CEO Sylvia Robinson. That same year, Lady B—a radio DJ hailing from Philly—released her song “To the Beat Y’all,” along with Lady D, who released her namesake track “Lady D” on the same 7-inch vinyl single as MC Tee’s “Nu Sounds.”

There was a certain level of cachet to women joining all-male groups. For years, women were waiting for that fateful moment to jump on the mic in the midst of an already-forming male-dominated platform.

In 1981, after Blondie’s Debbie Harry made history when “Rapture” became the first rap music video to air on MTV, she introduced Funky 4 + 1 on Saturday Night Live, making them the first hip-hop group to appear on national television.

More female artists and their groups flourished throughout the early ’80s, many under the umbrella of the Zulu Nation, led by pioneer Afrika Bambaataa. Lisa Lee, who was the first (and only) female in the Soulsonic Force (of “Planet Rock” fame), later joined the Cosmic Force. Sweet and Sour was part of Kool Herc’s crew The Herculords, along with Pebblee-Poo, who was with her brother’s Master Don & the Death Committee. Pebblee-Poo was also one of the first women to fly solo.

The “firsts” debate carries over into all-female groups as well. South Carolina’s The Sequence was the first all-female hip-hop group to cut a record (with Sugar Hill Records), though group member Angie Stone would later switch over to R&B. “They had the first hook I had ever heard on ‘Funk You Up,'” Kurtis Blow says of The Sequence’s 1979 single. Kurtis released “The Breaks” a year later. “A lot of people give me the credit for having the first hook— ‘These . . . are . . . the breaks’—but no, ‘Funk You Up’ actually came before that. I have to give them their props.'”

Then there are the Winley sisters, Tanya and Paulette. Their father Paul Winley turned his doo-wop label Winley Records into a hip-hop label, the first label to actually cut a record with Afrika Bambaataa. Tanya Winley was known on the solo front as the original Sweet Tee, predating Toi “Sweet Tee” Jackson, the prominent female MC who in 1986 scored a hit called “It’s My Beat,” featuring the legendary DJ Jazzy Joyce. As a group, the Winley sisters recorded the single “Rhymin’ and Rappin'” in 1979, and Sweet Tee dropped her solo track “Vicious Rap” in 1980. There’s a debate over whether Sweet Tee was the first female soloist to cut a record, since she recorded her song in 1979, the same year as Lady B’s “To the Beat Y’all,” but it wasn’t released immediately.

However, the Mercedes Ladies are universally regarded as the first all-female hip-hop group. Formed around 1976–1977 and composed of both MCs and DJs, it took the teenaged group a few years to gain significant traction, especially when male egos trickled into the equation. “When I first started deejaying, it was because I had seen [Grandmaster] Flash when I was fourteen,” remembers Baby D, a Mercedes Ladies MC/DJ from 1978 to 1983. Baby D was self-taught on the turntables, rocking house parties with the guys at the James Monroe projects in the Bronx. Baby D came into her own, however, when she met her mentor, Grand Wizzard Theodore, through an artist named MC Smiley (not to be confused with her groupmate RD Smiley). Theodore taught her the art of scratch, and it was on ever since. Baby D’s rep preceded her. “I was on par with Grandmaster Flash and Theodore, which kind of pisses me off because men back then. . .they would not acknowledge the females,” she says with a pitch in her tone.

“At one point, Grandmaster Flash. . .when we were talking, he told me, ‘You know what group really made us afraid?’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Mercedes Ladies.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because you? You are me. But you’re a female. Your MCs, they can rap. They’re like Melle Mel, Kid Creole, all of them. And what’s even worse is that you spin like me.'” Baby D credits Theodore for the skills, but Flash for the knowledge as it pertains to her navigation through hip-hop.

“Baby D was an incredible DJ,” Kurtis Blow says. He later made history when he took Baby D on tour, making her one of the first female DJs to tour with a male MC. “I actually stole her from the Mercedes Ladies and took her on the road for about two years,” he explains. “She was very fast and accurate on the turntables. Her style of cuts reminded me of Flash or Theodore. I think she was the best female DJ I ever saw.”

As much as Baby D was regarded as a skilled DJ, her rhymes were equally potent. She called herself “double jeopardy,” and Grandmaster Flash agreed. “But then when you sit back and listen to these cats talk, I’m like, ‘So when are y’all gonna talk about Mercedes Ladies?'” she says. “Sometimes I have to sit down and question myself if we were even there.”

Considering Mercedes Ladies still have to fight for a name check at all, Baby D isn’t particularly concerned with being first, but is adamant about being known as the foundation for all others that followed. “Mercedes Ladies is without a doubt the foundation of females within hip-hop,” she says. “We are the ones that busted our ass so that [Roxanne] Shanté and Sequence and Salt-N-Pepa and everyone else could go and do what they did. We did that. We fought that. We fought Starski.”

Starski?

The Mercedes Ladies are universally regarded as the first all-female hip-hop group.

It was a night in downtown Manhattan, maybe at the Palladium, but Baby D’s memory of the venue is cloudy. The era of the outdoor sound system wars had come to a close at the end of the summer of ’77, and performances had moved into the clubs during the colder weather. Lovebug Starski and Busy Bee Starski had just performed a clean set. Mercedes Ladies were onstage, but Baby D was in the back fighting with Grandmaster Flash. Various acts would often share equipment, and she had forgotten her needles and her records. All she needed were those records and needles, but Flash wasn’t giving them up without a lecture. She was annoyed, and Flash was angry. He raised his voice and D lost her mind. “You will not talk to me that way because I’m a female,” she yelled back.

It was part gender war, part lovers’ quarrel. “Of course at the time, me and Flash were going out,” she says now, with a laugh. Meanwhile, their bickering was drowned out by loud booing from the crowd. D ran out onstage behind RD Smiley’s turntables, the same set successfully used by Starski moments prior. Except now, they’re not working. “We were sabotaged,” Baby D says, believing Lovebug Starski to have been the culprit. “They would do crap like that to females that were good.” Whether refusing to lift heavy equipment or climb fences they had already climbed to plug in their own sound systems during outdoor sets, the men had a frequent response for women who asked for help: “Do it yourself.”

This time the saboteurs weren’t going to ruin Mercedes Ladies’ shine. Baby D and RD Smiley figured out the glitch (it came down to a simple dial turned all the way down). Flash handed her his records and needles and said, “Go save the show.” D walked back on- stage, tapped her groupmate Sheri Sher on the shoulder, and said, “Let’s do this.” Victory was achieved.

“We lit the stage up that night.”

__________________________________

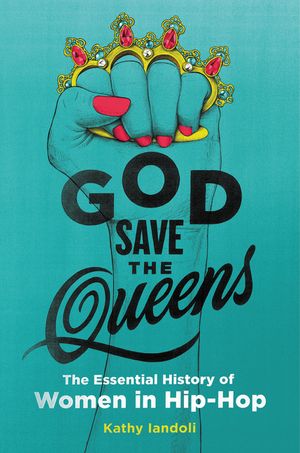

Excerpted from God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop by Kathy Iandoli. Copyright © Kathy Iandoli 2019. Reprinted with permission from Dey Street.

Kathy Iandoli

Kathy Iandoli is a critically acclaimed hip-hop journalist and author of God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop. She’s written for numerous publications including Vibe, The Source, The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and many more. A professor-in-residence of music business at New York University, Kathy routinely serves as a TV and radio panelist for discussions on hip-hop and gender. She lives in New York City.