On Dealing with Literary Rejection: The Importance of Letting Go and Moving On

Jessica Bacal Considers How Writers and Artists Deal

with Hearing “No”

Professional rejection is like romantic rejection. Remember how you went for a drink with the person who broke your heart because you were “still friends?” At goodbye, you hugged in the darkened doorway of your apartment building, which turned into making out. He came upstairs, and the next day you felt lonely and full of regret. When you pin your future hopes on a person—or a job, or a publication, rejection can wreak havoc on your identity. And the feelings rejection, even professional rejection, stirs up can hang around.

While you know those feelings are destructive, you’re drawn to them over and over again. You may be drawn to them even when you have plenty of experience with rejection; if you’re a writer, it’s inevitable once you start submitting your writing for publication. Or maybe you’re fairly new to rejection, having lost a job during the pandemic. If it led to the loss of vital income, then it likely caused real anxiety.

What I am arguing here is that rejection doesn’t have to be something that you spend time analyzing and unpacking and feeling. It doesn’t have to lead to cruel self-talk: “You didn’t work hard enough, it’s so embarrassing, how could you have thought… etc.”

You don’t have to over-identify with your rejection because you are not the same, just like you and [insert name] were actually two different people, ready to go your separate ways.

I figured this out over the course of a year, during which I wrote an entire book on rejection. I had the chance to interview many about their lowest blows and letdowns. I can assure you that my interest was purely professional and not personal—surely I didn’t have my own romance with rejection, ruminating on it and building up stories about how any rejection was “proof” I wasn’t good enough! Okay, maybe it was a little personal. And through interviewing participants for the book, I learned multiple strategies for moving on. My interviewees, all women, methodically collected nos; they learned to separate themselves from their work; they took the long view; they committed to a rigorous schedule of creativity; they treated themselves with kindness.

Those who sought out rejections included comedy writer Emily Winter, who embarked on a project to purposefully get rejected a hundred times. The catalyst was an intensive period of writing for a “packet” she submitted to Trevor Noah—as you may know, a packet is the collection of work that comedy writers put forth in order to be considered for jobs on The Daily Show or others like it. In that industry, writers don’t get rejections; instead, they’re ghosted or learn about their own failure through word-of-mouth.

“I found out via social media, which is pretty standard,” Winter told me. “Usually, you don’t find out until somebody posts a picture of themselves at what would be your desk, saying, ‘Oh, it’s my first day here!’”

Winter decided that she would begin to actively seek rejections, collecting them until she had a hundred, and this led to putting herself out there in new ways. For example, she told me, “I’d always been afraid to submit to The New Yorker. In my twenties, I was like, ‘I’m too young to write for ‘Shouts & Murmurs.’ Then, in my thirties, I was like, ‘I think I’m too dumb.’ But I wrote a piece and submitted it and they were like, ‘Yeah. We’ll run this.’ Then I submitted again, and they were like, ‘Yeah.’” This wasn’t the only success that delighted her—but she also got turned down literally 100 times. Compare it to the way you might push yourself to get over a love affair by speed-dating or right-swiping on Tinder.

Roz Chast, the cartoonist and memoirist, has also collected hundreds of rejections over her career; I was stunned to learn that most of what she draws for The New Yorker gets turned down. It was also eye-opening to hear Chast talk about her time at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where she felt like a terrible artist.

“I would bring my sad little thing in and everybody else’s was so much better,” she said. “I wasn’t even in the middle. I was sort of at the bottom as far as drawing skills went.”

She loved making cartoons, so when she found out that a group of RISD peers was starting a cartoon magazine called Fred, she was excited. Chast put together a portfolio, submitted it, and waited.

“There was a lawn with a hill in front of RISD’s freshman dorm,” Chast told me, “and I remember sitting down on the grass alone after I heard back from Fred. They wouldn’t take any of my drawings. I just sat on that hill by myself, weeping, crying like a baby. It was really crushing. It hurt a lot.”

If you are reading this in the wake of a rejection, consider projecting yourself into the future, having blown right past those who turned you down. Looking back, Chast said: “Now, of course, it’s many years later, and one thing I know is that none of the editors of Fred have gone on to be successful cartoonists. It would be an understatement to say that this fact gives me pleasure.” Hearing Chast talk about her early days, it seems helpful to try taking the long view, and to remind yourself that building a career takes patience—just like finding the right life partner, if that’s what you’re looking for.

Chast’s story about leaving Fred’s editors in the dust is resonant with another example from writer Michelle Tea. There was a moment in the nineties when Tea sent a book proposal to a prominent queer press called Alyson, which, according to Tea, represented the “white gay male prestige” topping the queer hierarchy of the time. Because Tea had just had success with a previous book, which had gotten attention in The Nation and The Village Voice, she was confident about this new proposal for Valencia.

But Tea received a form letter back. It was a rejection that made her wonder whether anyone had even read the proposal. She wondered if the book “was too dykey and too outside queer culture,” but instead of turning the rejection inward and deciding there was something wrong with the book, she didn’t take it personally. “It felt like a political injustice,” she told me, “like they didn’t care about this culture, but it also made me feel like more of a little queer outlaw. ”

If you are reading this in the wake of a rejection, consider projecting yourself into the future, having blown right past those who turned you down.

Valencia was published by another press and won the Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Fiction that year. Tea said that part of the lesson was: “Try not to over-identify with your creative work. It can feel like if somebody doesn’t like your work, then they don’t like you. But your work is this mysterious thing that comes out of you. It’s your job to serve it, help it, and then let it go and move on to your next thing.”

Letting go and moving on was what singer-songwriter Rachel Platten did in order to recover from a rejection that felt “like the wind had been knocked out of me.” Platten is the woman behind the radio hit “Fight Song”—as in “This is my fight song / take back my life song.” For years, she played at bars in New York City; eventually, a small label sent her around to sing in conference rooms at radio stations, bringing pizza and trying to charm DJs into playing her music. When RCA offered her a record deal, she felt like she’d finally made it. “This had been my ultimate goal,” she told me, “and I was so excited.” But right before she signed the contract, RCA changed their minds. She was devastated.

Still, Platten refused to get too attached to that feeling. “After a rejection,” she told me, “you have to stop your own destructive narration, the looping story in which you tell yourself what just happened.” How did she do that? She told me it’s “through creativity itself. That’s what breaks up the noise in your head and gets you back to your heart.”

Rigorous work kept her grounded, and eventually, Platten had a breakthrough with “Fight Song.” But even today, she still manages and resists the inner voice that tries to say “you’re not good enough.” While working on an upcoming album, she told me, “I’m catching myself in the loop again” and revealed that she practices meditation to get out of it; she also treats her “inner artist like a kindergartener in art class,” which means being “gentle rather than critical.”

Being gentle with oneself in the wake of a rejection is a good idea whether that rejection is coming from love or work; research psychologists advise us to take it a step further and actually talk to or about ourselves with kindness. Speaking encouragingly to yourself—or writing about yourself—can have a surprising impact on your resilience, according to Ethan Kross, a psychologist at the University of Michigan. His research shows that “distanced self-talk” helps people to separate themselves from a rejection, and also shows how.

“Imagine that a friend comes to you after a rejection,” Kross said. “You’d say, ‘You got one rejection. You’ve got to move on. There will be plenty of other opportunities for you.’” He’s found that it helps when people think about themselves in the same friendly way and talk to themselves with non-first-person pronouns. So rather than thinking, I was rejected, I must suck, you literally use narration in the second-person—“Jessica, you don’t suck”—or in the third person to write about yourself. Whether you do this internally or on paper, it can kind of trick your brain into objective and rational thinking. Kross says there’s evidence that “distanced self-talk” helps people cope with rejection.

When you think about ending a romance, sometimes you can’t imagine your life without that person. You’ve spent so much time together, and you’re used to having them on your mind. You wonder what they’d think or say in response to some piece of news, some Tweet, or bit of gossip because your identities have merged—just a little bit. And in the same way, you might inadvertently slide toward a kind of merging between yourself and a particularly painful rejection.

You might begin to believe that it wasn’t your writing that was rejected, or your resume, your qualifications, or work experience; it was you yourself that was rejected. But you are not your rejection, your rejection is not you, and it’s time to end the romance. It’s okay to move on.

__________________________________

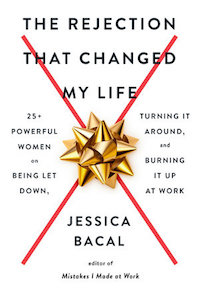

The Rejection That Changed My Life: 25+ Powerful Women on Being Let Down, Turning It Around, and Burning It Up at Work is available from Plume, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2021 by Jessica Bacal.

Jessica Bacal

Jessica Bacal is director of Reflective and Integrative Practices and of the Narratives Project at Smith College. She leads programs to help students explore identity and find resilience in community. She also teaches a course called Designing Your Path, which guides students to consider questions like: What is your story? Where have you been and where are you going? What matters to you? What skills do you need to pursue what matters? Before her career in higher education, she was an elementary school teacher in New York City, and then a curriculum developer and consultant. She received a bachelor’s degree from Carleton College, an MFA in writing from Hunter College, and an EdD from the University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Northampton, Massachusetts, with her husband, two children, and two dogs.