In 2008, Foxtel ran an ad campaign for the TV series Dexter. Michael C. Hall, who played the titular serial-killer-with-a-heart-of-brass, sits at an airport boarding gate. A fellow passenger asks him every South Australian’s least favorite question: What’s in Adelaide? Shark-eyed, Hall replies, “Adelaide has more serial killers per capita than any other city in Australia.” It was another riff on the undead idea that the state of South Australia (SA) is “the murder capital of the world.”

That nickname came from a 2002 British documentary, The Trials of Joanne Lees, which vivified the ordeal of two English backpackers attacked by a stranger on the Stuart Highway in 2001. But SA’s reputation as a mecca for murderers had really taken root decades earlier. The state is home to, among others, the Somerton Man (cold case featuring a supposed Soviet spy, 1948), Sundown (carjacking and shooting, 1957), the Beaumont Children (still missing after their abduction from Glenelg beach, 1966), Truro (serial thrill killings, 1976-77), the Family Murders (organized kidnapping, torture, murder of teen boys, 1979-83), and Snowtown (infamous “Bodies in the Barrels” case, 1992-99). These cases ferment in the state’s collective consciousness, if not its conscience. I was 14 when The Trials of Joanne Lees aired, and I remember people in my rural hometown being stoked that our state had made international headlines. Sometimes it feels as if locals collect tragedies like stamps—though statistical evidence for the “murder capital” assertion is hard to quantify.

In the same year that Foxtel was un-marketing Adelaide, the Australian Institute of Criminology advised that SA’s homicide rate (that is, murder and manslaughter combined) was actually 0.8 deaths per 100,000 people—30 per cent below the national average. In fact, it was as low as the national figure for 1941, when almost half a million Australians were offshore fighting in the Second World War.

Sometimes it feels as if locals collect tragedies like stamps.During the 1970s and 80s, homicides multiplied across the country as they did around the globe. South Australia wasn’t subject to the volume of homicides happening in states with larger populations, like Victoria and New South Wales, but it did experience a comparatively high rate per capita. Nationally, the homicide rate peaked in 1988, the year I was born, with almost 2.5 deaths per 100,000 people. The figure has markedly fallen since then in all states except the Northern Territory, where the chronic underfunding of social services, among other forms of systemic discrimination, continue to devastate Indigenous communities.

Perhaps Dexter got his data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2008 report, Prisoners in Australia. It notes that over 15 per cent of SA’s prison inmates were convicted of homicide, at a time when the national average was 10.4 per cent. Perhaps he just reads the local Murdoch rag The Advertiser, with its pious penchant for law, order, and morality. Either way, South Australia has always had fewer actual deaths by homicide, including murders, than have most other Australian states. Maybe the reason for our misplaced infamy is not the number, but the nature—often shockingly violent and expertly coordinated—of South Australian murderers, many of whom remain unidentified, and probably always will.

In 1984, Salman Rushdie appeared at Adelaide Writers’ Week, where he noted that our flyover city by the sea was “the perfect setting for a Stephen King novel.” Decades later, King did write a story inspired by the so-called murder capital. Though it was set, like most of his work, in the author’s home state of Maine, the book blatantly borrowed from South Australia’s favorite cold case: the mystery of the Somerton Man. “Things here go bump in the night,” observed Rushdie, tapping the immortal fears and persistent myths that South Aussies love to lean on.

*

The sun is setting on a late-winter Thursday as I walk up to Z Ward, a red-brick relic of the Victorian era. The building is only two floors tall, but to call it ‘imposing’ feels like an understatement. When this sickbay for the “criminally insane” opened in 1885, it was first called “L Ward,” one of several in the wider Park Side Lunatic Asylum. But “L Ward,” when uttered over the phone—particularly by British migrants prone to dropping their aitches, Guvna—sure sounded a lot like “Hell Ward.” The comparison was far too real and so the name was soon changed, remaining Z Ward until the building was mothballed in 1973. For forty years it was monitored only by eucalypts and palm trees, swaying on opposing sides of its eight-foot iron gate.

As the name suggests, dark history explores humankind’s seamiest, scariest chapters.Z Ward secretes despair, and a thick, sticky unease wades in as I realize, I have to go inside. This 11th-hour anxiety always grabs me just before a ghost tour; it’s the same dread I felt when my nanna caught me, age nine, sticking two fingers up at a traffic cop. Across the gravel driveway, Alison Oborn hauls recording equipment from the back of a sleek sedan. The whole driver’s side features a decal: a full moon rising behind the words “Ghost Tours,” scrawled in Chiller font. Alison’s company Haunted Horizons runs dark history talks in Adelaide Gaol, Adelaide Arcade, Torrens Island Quarantine Station, and here at Z Ward.

Inside the repurposed rec room, we sit at one end of a trestle table as daylight fades in the arched windows. The walls are sage, a sickly shade used in medical institutions to keep patients subdued. I wonder what other means the staff here used to that end. I wonder how the land felt before it was razed to make way for bricks and mortar, lithium and morphine. There are gumtrees and lorikeets outside, but I struggle to picture the terrain before invasion. I’d say I have no reference point, but that just feels lazy.

“It’s another way of bringing history screaming back to life, what we do,” says Oborn. “There’s a generation now that don’t want to go into moldy old museums. How do you get them in? Give them dark history.”

As the name suggests, dark history explores humankind’s seamiest, scariest chapters. Its commercial cousin, “dark tourism,” has roots stretching back to ancient Rome’s gladiatorial death matches, though it wasn’t formally theorized until 1996, when Glaswegian academics John Lennon and Malcolm Foley started analyzing tourist experiences linked to the assassination of former US President John F. Kennedy. Now a global phenomenon, dark tourism invites punters to step right up and pay admittance to places steeped in grief, from the Catacombes de Paris to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The “suicide forest” at Aokigahara to Alcatraz Island, where tours to the prison sell out weeks, even months, in advance.

Dark history also repeats in South Australia. Care of spooky walking tours, ghost hunts and paranormal lockdowns, where tales of the state’s most infamous murderers engross locals and tourists alike. As such, enterprises like Alison’s are good for history boffins, and great for the economy. While factories close and small businesses fold, dark tourism thrives in the Festival State, bringing a whole new meaning to the term “murder capital.” Unlike many of our arts and cultural events, Haunted Horizon’s tours regularly sell out, especially when the weather’s nice. Capitalizing on this bull market for murder stories, a number of other operators—Ghost Crime Tours, Spirited SA, and Lantern Ghost Tours, which operates nationally—have staked their own claims, with the local History Trust and Adelaide Cemeteries Authority following suit. What’s stoking this curiosity for the horrid?

“You think this is new?” Oborn asks. “It goes back to the 1800s. People were paying [to see] executions. In England, thousands would turn up.” I knew about the British crime broadsides that illustrated hangings in inky black and white, but—perhaps naïvely—I wasn’t aware that spectators flocked to watch deaths live, in the flesh. I’d like to think that the contemporary interest in true crime (or my personal investment, at any rate) isn’t quite so salacious, but that’s probably disingenuous, too.

What’s stoking this curiosity for the horrid?“Adelaide Gaol used to do public executions in the carpark,” Oborn goes on. “Two and a half thousand people would turn up, most of them were women and children. That’s a huge percentage of Adelaide back then.” Bleak as it seems, a ticketed (non-sporting) event in Adelaide with a turn-out of 2,000 people—from our current population of about 1.2 million—would be a raging success in 2019. (Take it from this recovering digital marketer who spent half a decade peddling tickets to our state’s finest, unattended festivals.)

Oborn has noticed that it’s mostly millennial, xennial and some boomer women who attend her tours, and activity on Haunted Horizon’s Facebook page reflects this. (In my experience on ghost tours, the groups have also been predominantly white.) I think of all the daughters cautioned by primetime Crime Stoppers in the 90s, those largely responsible for the zeitgeist’s feminist—or, at least, female—reclamation of true crime by way of podcasts, documentaries, and lively online communities.

Oborn suggests that fascination is just part of who we are.

“Somewhere deep in us, as an animal, there’s still that darker side. That scares us.” Dark tourism, she says, appeals to the part of us that wants to understand why a human commits acts of violence. Would we be able to spot it? “That’s why we watch all the serial killer shows. We want to know what drove that person.”

This sentiment is mirrored in the juggernaut podcast My Favorite Murder’s million-dollar mantra: “Stay sexy, don’t get murdered.” Irrational as it may seem, many true crime fans—myself included—hope to weaponize these stories against a real and present danger: the global scourge of gendered violence. In our haste to “pepper spray first, apologize later,” as hosts Georgia Hardstark and Karen Kilgariff recommend, nuance and compassion sometimes take a backseat.

Similarly, ghost tours—especially in old “asylums”—often play to the misconception that folks affected by mental illness are inherently dangerous. As a historian and storyteller, Oborn emphasizes that many “villains” may also be victims of childhood abuse and neglect: building blocks that can sustain a noxious cycle of adult violence. “These people, they’re dead and gone. It doesn’t matter to them,” she says of the murderers and rapists (and the ‘difficult’ patients shunted over from low-security wings) condemned to Z Ward. “But hopefully I’ve made their names mean something [and] they became your teachers. You learned a bit about society, a bit about the building, through their tragedies, but through their lives as well.”

True crime discourse is often reactionary, defensive, and lacking in nuance. Such willful sensationalism and ignorance had made me wary of this particular jaunt’s title, “Z Ward Asylum: Murder and Madness.” I’d been burned before; on an after-dark tour of one of Adelaide’s cemeteries, the guide wore a hooded, black velvet robe. She spoke in thespian tones of a circus trainer eaten alive by his tiger in front of their audience. She bantered with a guy in Dickensian garb and a borrowed Cockney accent, who had emerged from behind a headstone to portray the cemetery’s first sexton, whose real bones rested below.

Dark tourism appeals to the part of us that wants to understand why a human commits acts of violence.“All over the world, they dress up as characters,” says Oborn. “A lot of tourists want the costumes, the pantomime,” she says. “Perhaps it detaches them from the reality of it. If I dressed up as a warden or a patient in here . . . I couldn’t think of anything worse.” The lack of theatricality clearly resonates, she says, referring to Haunted Horizons’ swathe of awards. In addition to gongs from the SA Tourism Industry Council, Haunted Horizons has been nominated for a Telstra Business Award three years running. When done well, dark tourism helps society confront its historic failure to provide adequate, timely mental health care that could prevent tragedy. Indebted to folks who were unwell, outside, and othered, the industry has an obligation to remind its more voyeuristic participants that trauma itself has always been a prison.

Then there are the ethical implications of making money from murder. In Australia, this prohibits law-breakers from profiting off their dirty deeds. If a murderer can’t monetize their story, why can someone else? Alison assures me that roughly two-thirds of Haunted Horizons’ takings go straight back into the local economy via overheads, like venue costs. “I won’t say how much we give to the National Trust but it’d keep a lot of buildings alive,” she notes, adding that one to two dollars from every ticket sale is donated to the non-profit organization Beyond Blue.

The tours I’ve been on did appear to help punters make sense of colonial hardship. But it’s important we consider those who are missing from the national ghost story canon, too. On the tours I’ve done, guides seemed fixated—intentionally or not—on Australia’s favorite myth, that of the suffering “settler.” Tales tell of the English, Irish, German, and Dutch immigrants who perished on South Australia’s “hostile” landscape (which they rooted with European wheat and sheep). Scripts are saturated with sailors, wardens, sex workers, even circus animals, while the Peramangk, Ngadjuri, Nukunu, Naraŋga, Barngarla, Adnyamathanha, Kaurna and other Indigenous ghosts are conspicuously absent. Only one of seven tours I’ve experienced included an Acknowledgement of Country.

“My family’s grown up being told not to be afraid of the dead,” says Brodie. “It’s the living that’ll hurt you.”Googling the term “Kaurna ghosts” does return a link to Haunted Horizons’ website. The relevant page details a dark history tour in Gawler—the oldest country town in SA, about an hour’s drive north of Adelaide—and mentions that Kaurna people were/are the original custodians in that part of the state. The copy describes life in the area circa 1835, noting that the “Para Rivers would be flowing more freely with natural springs feeding the waterholes along the way,” where fish and yabbies were abundant. Children would have played in “the life giving waters . . . blissfully unaware of the great change that was about to come.” The passage ends, “Sadly they left little record of their culture or language.” Given the genocidal nature of settlement/invasion, this scapegoating strikes me as deeply shocking.

Then again, it really doesn’t.

*

To Shaun De Bruyn, CEO of the SA Tourism Industry Council, tours like Oborn’s are “almost heritage tourism. It’s part of who we are.”

As for whether the “murder capital” moniker has primed local interest in such tours, de Bruyn’s not convinced. “When they talk about South Australia as the ‘serial killer capital,’ I think it’s BS,” he says. He has another theory.

“This may make you laugh. I’m sure if I told my kids, they’d think I was off with the pixies. Because we were a free-settled state, unlike [the] penal colonies, we were seen as being more refined, more civil. When something terrible does happen, it’s more shocking for us.

“You almost feel like: two hundred years ago, we’re totally disconnected from it. But it’s probably still part of our DNA to some degree, part of our psyche and how we think of ourselves.”

Which might be true, at least for those whose families landed two centuries ago. It’s not really applicable to anyone whose ancestors arrived later or, moreover, before.

*

I first met Margaret Brodie this summer when she hosted a cultural walk along a Kaurna trail near Port Adelaide—a spot once known as “Port Misery” thanks to the mosquitoes, mud and murders that displeased so many white immigrants arriving in the 1800s. The once-industrial area now resembles any of those dockside precincts where council-approved renewal can’t quite gentrify the sorrow. In April 2019, the creepy flour mill still throws its shadow toward a waterfront café where I meet up with her and her friend, Tina. Inside, we leap to the window to watch a dolphin arc down the Port River.

Brodie’s great-great-grandmother Lartelare called these parts Yerta Bulti—“Sleeping Place”—honoring a story about fish dying peacefully in the mangroves. Like her foremothers, Brodie is a Kaurna Elder who’s lived here for most of her life. She’s never heard the tale about Port Adelaide’s phantom panther, who stalks the docks at night, sniffing out the local vet who euthanized him, but she has untold ghost stories of her own.

“As I get older, I believe ghosts are everywhere, we just don’t always see them,” she says. “Our dead aren’t there to frighten us. They’re carrying a message.” Tina nods in agreement.

Just as velvet cloaks soften the retelling of historic suffering, so too do the ghost stories, themselves.Brodie explains how benevolent ghosts—called “kuinyu” in Kaurna Warra—usually denote unfinished business. Spirits may only show themselves to one person in a packed room, thereby compelling that individual to consider the vision’s significance and purpose. Malevolent “boopa” are more akin to demons, but they still require the same empathetic contemplation.

Most of Margaret and Tina’s yarns describe visits from family members. But dotted through stories of flying hairbrushes, spectral neighbors, and freaky kids who vanish on the roadside near Ceduna, the women talk of seeing specters of non-Aboriginal people, too. I mention that, on the ghost tours I’ve undertaken, no one has ever remarked on the ghosts of Kaurna Meyunna, or Kaurna people.

“It breaks my heart that we weren’t meaningful enough as a people,” says Tina. “Nothing about us matters.” She mentions the countless Indigenous burial grounds desecrated in aid of industry, agriculture, imperialism. We could be walking over them every day.

“That ugly big boat down the end there, I reckon that’s haunted,” says Brodie. I reckon she’s on the money. When the decaying clipper ship City of Adelaide was brought here by a volunteer group in 2014, Ghost Crime Tours started running paranormal lock-ins onboard. For a fee, amateur ghostbusters could use professional equipment to contact any residual spirits. I remember hearing a story about a pair of disembodied sailor legs that left the ship at night, meandering across the road to the Port Dock Hotel.

Tina’s view of the vessel is more sombre. “That is our past,” she says. “It’s a replica of what they’ve done to us: We’ve come here, we’ve taken your land. This is how it is.”

“My family’s grown up being told not to be afraid of the dead,” says Brodie. “It’s the living that’ll hurt you.” She feels her ancestors are here to direct her. When she drives into the old Port MacLeay mission (now Raukkan), Brodie sees them on the hills, waving her in and out. “But it’s only my vision,” she adds.

“I swear if we sit here long enough, they’ll be waving to us across the river there.”

*

South Australia’s free-settled, Festival State, murder capital myths may be debunked, but other transgenerational consequences live on. Just as velvet cloaks soften the retelling of historic suffering, so too do the ghost stories, themselves. More than just a temporary portal to the past, dark tourism creates safe spaces to face fears of shadowy places, empty streets, the corners we tell young women to avoid. Oborn was terrified of the dark until the Adelaide Gaol forced her to confront it. Likewise, I dally with dark tourism to desensitize myself against (what feels like) inevitable violence. Now I know what makes a human being do this, I’m able to spot it, and I see it everywhere. The once “unimaginable” horror of homicide feels pandemic, with podcasts, newsrooms and prestige TV all catering to avid murder-thirst. Nothing brings folks together like touring through other people’s trauma. For that, I’m guilty as charged.

Yet there’s one entrenched terror we can’t bear to address. Terra nullius. The true crime that launched them all in so-called “Australia,” where we plonk our eskies down on burial grounds, crack a coldie for the battlers, the mad cunts, the good blokes. Where we say ghosts manifest when a life is “stolen.” Imagine the future tourists ushered through Adelaide Remand Centre and Don Dale. It’s just a matter of time and money.

Ghost stories can act as narcotics, or blunt objects, but the sheer will of colonial myth-making will never foment for settler-migrants any emotional connection to the stolen land on which we trespass. Our boats, pubs, prisons, museums: they help us see the world as we’d have it, but you can’t make a scrying crystal from red brick. Dark tourism might help white Australians metabolize our history of trauma, but it alone won’t heal the trauma of our history. Don’t buy a ticket if you can’t pay the rent.

______________________________________

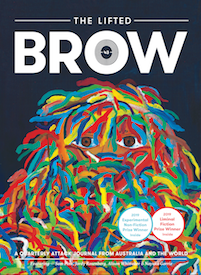

From Aimee Knight’s Pop-Culture column featured in Issue 43 of The Lifted Brow (September 2, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Aimee Knight.