On Contemporary Minimalism's Maximal Lies

Andru Okun Reads Kyle Chayka, Jenny Odell, and Oli Mould

Kyle Chayka’s The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism arrived in the mailbox at the same time my partner and I were embarking on a move. Our 750-square-foot apartment filled up with boxes, sharpie-scrawled with labels like “books,” “kitchen junk,” and “desk stuff.” We were moving to a slightly bigger, moderately nicer apartment a few blocks over. Still, a part of me wanted to throw everything away.

Chayka explores what seems like an obvious enough premise: Westerners’ lives are cluttered, full of stuff that can’t actually make us happy. The incessant longing for more leaves us feeling empty. He writes of an American populace “addicted to accumulation,” putting the number of household possessions in the average American home at around 300,000 items. Our current form of consumer-driven late capitalism—bolstered in part by a global network of cheap, exploitable labor and the unbridled access to commodity goods provided by online retail—allow for a large subset of the population to have lives full of stuff attained with a relativity of ease unimaginable 10 or 15 years ago. And yet, we remain chronically unfulfilled, the yen of materialism knowing no bounds.

Seemingly in direct response to such excess, minimalist aesthetics have grown in popularity and evolved into a bonafide lifestyle trend amongst Westerners seeking a cure for psychogenic emptiness through physical austerity. This present day form of minimalism-as-lifestyle responds to the commodification of daily life by rejecting things. But this aesthetic of rejection—often referred to with the misnomer of “simplicity”—has itself been commodified and absorbed into the shallow world of consumerism.

Tracking the recent resurgence of minimalism in the form of ascetic lifestyle bloggers and pop culture figures like Marie Kondo, Chayka writes on how the movement to get rid of stuff has become permeated with the desire to replace said stuff with new, better stuff. More minimalist stuff, like “mid-Century boho” furniture and housewares, “lifestyle goods” sent directly to consumers by minimalist subscription services, and minimalist smartphones so stripped of functionality they dissuade users from interacting with them. This last point I can attest to, as I’ve had a Unihertz Jelly Pro for a year and a half—it has both cut back significantly on the amount of time I spend staring at a screen, as well as diminished most of the practicality of carrying a phone in the first place.

This pull toward a more ascetic lifestyle speaks to a desire to learn something about our relationships to possessions, but what exactly? When we empty out our spaces, apartments’ worth of belongings stuffed into black contractor bags and dropped off at the nearest Goodwill, the next question, as Chayka asks, presents itself: “And then what?” In such a seemingly simple question is the intimation that perhaps this materially focused form of minimalism, so wrapped up in a culture of consumption, falls short. “Minimalism is just one way of thinking about what makes a good life,” writes Chayka, “though it’s a strategy that’s particularly relevant to the superhuman scale and pace of our time.”

When thinking of minimalism, the line between art and retail is blurry at best.

Recent books like Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy and Eriling Kagge’s Silence: In the Age of Noise speak to the cultural distress engendered by existing in a time out of order, our senses overloaded and our quality of life attenuated by the “more is more” ethos of modernity. Our phones and laptops, ostensibly designed to enhance connectivity and the everyday experience of being alive, have turned out to be habit-forming wellsprings of anxiety and oppression in a world of escalating precarity.

In Chayka’s estimation, minimalism provides an opportunity for a different kind of attention. To lessen or reduce, to embrace absence, provides a feeling of control. And yet, as Chayka notes, a minimalism that is merely an individualized pursuit rooted in materialism will likely fail to diffuse the collective share of human suffering. “Your bedroom might be cleaner,” he writes, “but the world stays bad.” If minimalism is to have real consequence, it will need to be understood beyond its current iteration as an Instagrammable lifestyle trend. Chayka seeks to bridge this divide.

Beginning as an inquiry into “the generic luxury style of the 2010s,” The Longing for Less grows into a percipient examination of art, architecture, and music. Moving beyond the etymology of “minimalism,” the author looks toward Buddhist philosophy and Japanese aesthetics, reflecting on seminal Japanese texts like Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s “In Praise of Shadows,” an essay on traditional Japanese culture and aesthetics.

In a brightly lit and busy world, maintaining the composure necessary for thoughtful observation is a glaring challenge.

I wasn’t familiar with Tanizaki prior to The Longing for Less, but Chayka’s musings on the essay piqued my interest. I sat down one afternoon with the slim treatise—first published in 1933 in Japanese and translated into English in 1977—curious to learn more on how a text written nearly 90 years ago related to modern day minimalism. Setting aside Tanizaki’s anachronistic opinions that are difficult to categorize as anything but casual racism and misogyny, his pensive reflections on traditional Japanese aesthetics convey an elevated appreciation of subtlety. He speaks with great reverence of the traditional Japanese home, lacking in modern amenities but possessing the austere beauty of uncomplicated utilitarianism. Wood is preferable to tile, and paper preferable to glass. He writes of the toilet as a place of “spiritual repose.” He bemoans appliances like gas stoves and electric fans, but he reserves particular ire for lights.

For Tanizaki, the forces of globalization and Western influence had changed the aesthetic nature of Japan, and nowhere was this more evident than in the omnipresence of electrically powered lights. In homes and hotels, restaurants and theaters, lights were destroying the subtle allure of darkness. “Were it not for shadows,” Tanizaki writes, “there would be no beauty.”

In Tōkamachi, a small town in the countryside of Japan, visitors can spend the night inside of an artwork-cum-guesthouse inspired by Tanizaki’s essay. “House of Light” was created in 2000 by the American artist James Turrell, who “wished to realize the ‘world of shadows we are losing,’ as Tanizaki wrote.” Like much of Turrell’s work, “House of Light” utilizes light as both medium and subject, with elements of design and architecture incorporated to create perceptual phenomena. Built in the style of a traditional Japanese home, the house features a sliding roof with a square cutout for sky observation. Light is not only observed, it is experienced—as the sky changes, so does the work.

“House of Light” by James Turrell. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

“House of Light” by James Turrell. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

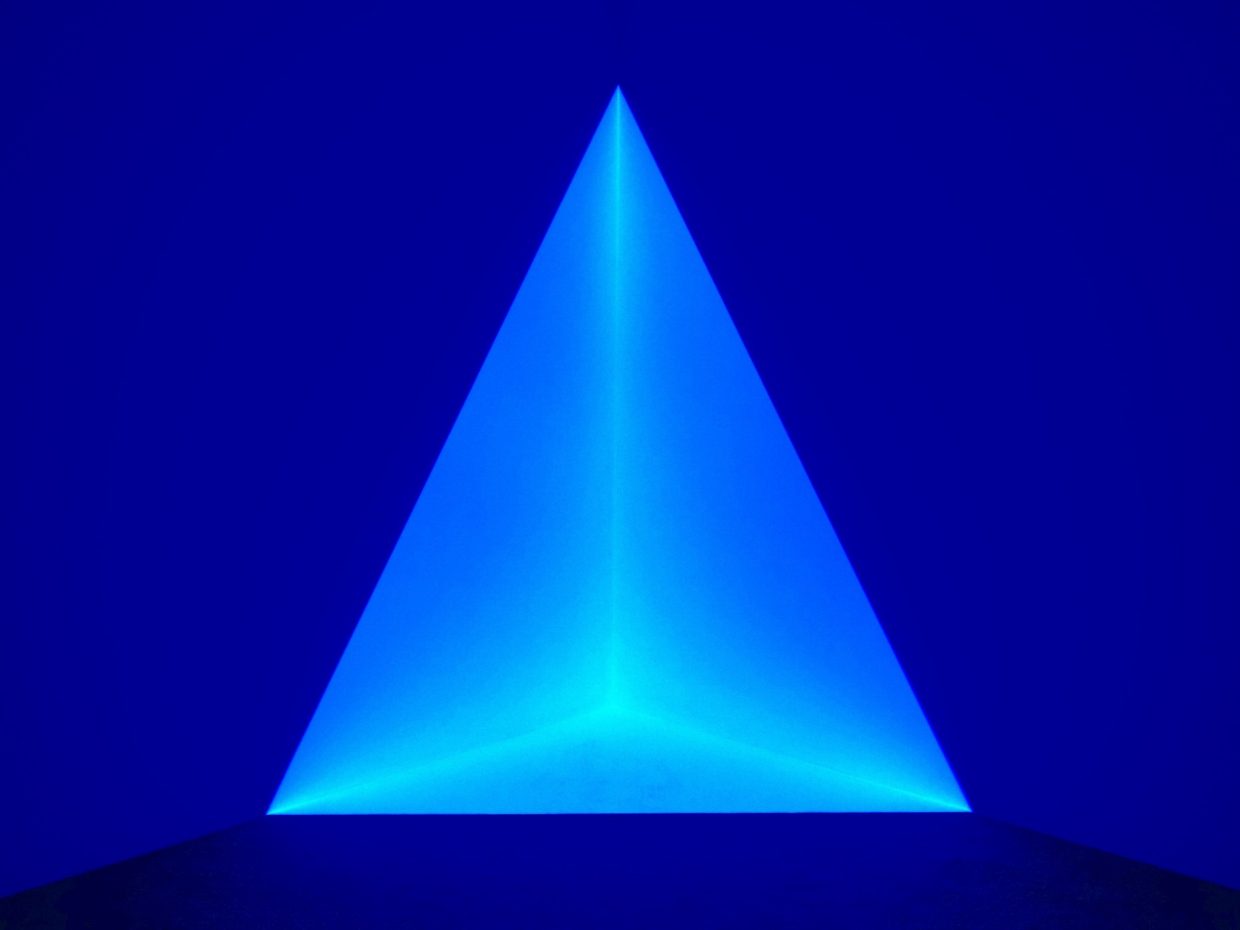

While not by definition a minimalist artist, there is a quality to Turrel’s work that speaks to a similar aesthetic sensibility. Turell, whose work has been greatly influenced by his rearing as a Quaker, produces art that is often described as meditative. Some of his pieces are astonishingly ethereal, while others are so intense they require the viewer to sign a waiver before viewing. A deceptive simplicity permeates much of Turrell’s work, defined by one critic as “dull to describe but magical to experience.”

While conceptually very different thinkers, where Turrell and Tanizaki may most closely align is in their shared appreciation of darkness and the opportunity it provides for observation. Long before constructing his Tanizaki-inspired home, Turrell was experimenting with achromatic space. His series of “Dark Spaces” immersed viewers in tenebrous rooms that demanded protracted engagement in order to be fully experienced. Christopher Snow Hopkins, writing for Hyperallergic in 2017, described one of Turrell’s dark spaces (“Hind Sight,” 1984):

A dark chamber devoid of visual or aural stimuli (apart from the exhalations of an air duct). The experience is similar to falling asleep, as physical reality recedes from consciousness and the viewer enters a meditative state. After 10 to 15 minutes, the viewer’s pupils are fully dilated, at which point the viewer is called back to the material world by the presence of a dim light on the opposite side of the chamber, so faint that it can only be perceived in the viewer’s peripheral vision.

In order to achieve the full effect of a Turrell dark space, described by the artist as “seeing yourself see,” you have to wait. Patience is not merely a virtue, it’s a requirement. My own experience of being enveloped in the deep, prodigious blackness of “Hind Sight” was one of anticipation followed by awe. The darkness provided an opportunity for stillness, and once I was able to move past my own expectations of what I was meant to see, I experienced the piece.

“Gard Blue” by James Turrell. Photo via Flickr user Dean Hochman.

“Gard Blue” by James Turrell. Photo via Flickr user Dean Hochman.

In a brightly lit and busy world, maintaining the composure necessary for thoughtful observation is a glaring challenge. Toward the end of his essay, Tanizaki writes, “Never has there been an age that people have been satisfied with.” Not unlike many of us today, he laments the hurried speed of progress. Contemporary minimalist aesthetics are a direct response to this speed and the collective malaise it has inspired, and Americans, a definitively aspirational group, are particularly susceptible to the tenets of such a movement. Chayka, most astute as an art critic and cultural observer when rooted in familiar terrain, captures the mythos that define the country’s minimalist predilections, noting that, “Something about our belief in the power of self-definition and starting over suggests to us that if we only sweep our floors we will magically become new people, unburdened by the past.”

Chayka observes that what’s recognized as minimalism today (“white T-shirts, mono-chrome apartments, and wireframe furniture”) has little in common with the post-World War II avant-garde visual art movement that inspired it. Minimalist artists often used industrial materials like steel, aluminum, and fluorescent light tubes to create their works. They would draft renderings of sculptures and have them fabricated at factories, representing a conspicuous departure from the traditional paradigm of artist and object.

Sculpture by Donald Judd. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Sculpture by Donald Judd. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps the premiere minimalist artist of the 20th century, Donald Judd is an important figure in The Longing for Less. Successful but dissatisfied, Judd sought to leave the New York art world of the 1970s. He began buying real estate in the tiny West Texas town of Marfa, gradually acquiring abandoned airport hangars, artillery sheds, and other properties throughout the town. He lived with his family in the former offices of the US Army’s Quartermaster Corps, working over decades to transform the sparsely populated desert town into his own artistic reliquary. Addressing what made minimalist artists like Judd so radical in the 1960s and 70s, Chayka cites that “the art object did not have to represent anything, document reality, or even communicate the artist’s individuality… Sensation replaced interpretation.”

*

In 2017, my partner and I took a road trip through West Texas. Trump had taken office a few months prior, and one of his many senseless threats as president was to build a wall through Big Bend, an extremely remote national park bordering Mexico. In the days after the inauguration, the endless barrage of bad news had become difficult to process. The impulse to see a beautiful place endangered by a despotic administration became a strong, easily understood feeling, a place to start.

From New Orleans, we drove our subcompact rental car for over 15 hours, around 1,000 miles, arriving at the massive plot of earth that is Big Bend. Being roughly the size of Rhode Island, Big Bend is one of the country’s largest parks; as isolated as it is, it’s also one of the country’s least visited. Javelinas and roadrunners seem to outnumber people. In surroundings of epic scale, so stunningly secluded, it was difficult to imagine how the cacoethes of narrow-minded xenophobia could justify carving such a violent obstruction through such an awe-inspiring landscape, forever altering 800,000 acres of protected wildlife and ecology in what would amount to at best a Pyrrhic victory.

My partner and I camped for several days in the park, taking in the grandeur and seeing very few people. We hiked through chasms in the early mornings, huge walls of rock towering above us. In the Chisos Mountains, we rested on cliffs overlooking the incomprehensibly vast Chihuahuan Desert. During the hottest part of the day, we drove, listening to Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind and stopping to look at the park’s outdoor exhibit of dinosaur fossils. For respite, we waded through the shallow parts of the Rio Grande, crossing back and forth between the US and Mexico enough times that the division between the two no longer held any meaning.

The presage of destruction can be a catalyst for observation; nature is good for providing perspective, reminding us of both our own insignificance as well as the interconnectivity of things. While the decision to visit a place as remote as Big Bend was informed in part by the instinct to see something before it was potentially destroyed, it was also shaped by the desire to avoid the sameness of contemporary travel destinations, where the space and time necessary for reflection is often hard to find, if not altogether absent.

As I’ve gotten older, visiting unfamiliar cities only to find myself in places similar to the places I frequent back home has lost its appeal. The rampant gentrification of major American cities over the past decade has displaced hundreds-of-thousands of low-income residents and turned many urban spaces into two-dimensional playgrounds for the rich. A purely transactional world feels meaningless, and there’s a particular ennui that accompanies the act of visiting a place primarily to spend money.

Moreover, so many of these places now look the same. In a 2016 article for The Verge, Chayka writes on “AirSpace,” a term he coined to describe the contemporary aesthetic homogeneity of cities. Think “minimalist furniture. Craft beer and avocado toast. Reclaimed wood. Industrial lighting. Cortados. Fast internet.” This cultural flattening—a byproduct of digital platforms like Foursquare, Instagram, Yelp, and Airbnb—allows for “frictionless travel,” the ability to travel to a far off city or country and still manage to be in pretty much the same place.

Mountains near Terlingua, Texas. Photo by Flickr user Jonathan Cutrer.

Mountains near Terlingua, Texas. Photo by Flickr user Jonathan Cutrer.

Upon leaving Big Bend, we stopped in nearby Terlingua, Texas, a former mining town (population: 58) a hundred miles outside of Marfa. Amongst a bar bathroom’s plentiful graffiti was a candid missive: “FUCK MARFA.” We drove past a border checkpoint, past Elmgreen & Dragset’s Prada Marfa installation, and arrived in the tiny town now so closely associated with the minimalist movement.

Present day Marfa is a popular tourist destination that has been covered by the likes of NPR, Vogue, and The New York Times. An influx of wealthy outsiders has resulted in a sharply increased cost of living for local residents; adobe homes sell for $1 million in a county with a median income of $29,000. As Chayka observes, “Judd hadn’t built all this so you could get a nice homemade pasta dish and a glass of rosé in the desert… These days, though, you can go to Marfa on vacation and not think about the artist at all. Plenty of people don’t.” While Judd—who died in 1994—sought emptiness and a retreat from homogeneity, if he were searching today he would likely have to look elsewhere.

In Oli Mould’s 2018 disquisition Against Creativity, the urban geographer dissects the paradigm so often reflected in the relationship between art and gentrification. He posits that 21st-century capitalism, “turbocharged by neoliberalism,” has co-opted the conceptual framework of creativity in the interest of endless growth. Even movements interested in destabilizing capitalism can be “viewed as a potential market to exploit,” subsumed by the very world they seek to transform. “Creativity under capitalism is not creative at all… it merely replicates existing capitalist registers into ever-deeper recesses of socioeconomic life,” writes Mould.

Photo via Flickr user Nicolas Henderson.

Photo via Flickr user Nicolas Henderson.

This commodified variation of creativity, defanged and depoliticized, has contributed to what Mould refers to as the “slow violence” of displacement and dispossession. This slow violence is perhaps most evident in American cities where neoliberal urban planning policies bolster the “creative class” in the interest of economic gain. In particular, the presence of art and artists can serve as a boon for property values and speculative real estate ventures. In seeking space, artists often rubber stamp their own removal, all but the most financially secure among them priced out by their own presence. That Judd’s Marfa has turned into a beacon for luxury tourism demonstrates that even a remote desert town, with a population of less than 2,000, is not exempt from the whims of capital.

As Mould argues, “Neoliberalism is about the marketization of everything, the imprinting of economic rationalities into the deepest recesses of everyday life.” Due to its means of production and its correlation with domesticity thanks to artists like Judd and Philip Johnson, the visual aesthetics of avant-garde minimalism were particularly ripe for commodification. When thinking of minimalism, the line between art and retail is blurry at best. An early Sol LeWitt sculpture could rightfully be confused for a piece of Ikea furniture, Louis Vuitton makes Yayoi Kusama handbags, and Urban Outfitters has its own selection of minimalist wall art. In an ironic twist, an aesthetic of austerity has been absorbed into the world of consumer goods. “The veneer of minimalism,” as Chayka writes, has become “another class-dependent way of feeling better about yourself by buying a product.”

We want the world to be less complicated, but the aesthetics of superficial simplicity don’t provide an easy solution.

As a consumer driven aesthetic, contemporary minimalism seeks blankness. Perhaps this is best exemplified by our phones, so sleek and simple in appearance, yet undeniably dependent upon a complicated network of server farms, factories, and mining operations, referred to in Against Creativity as “a vast and growing ‘material’ infrastructure—one that is ravenous for resources.” This resource reliance speaks to the rarefied set of privileges that informs so much of modern day minimalism, an often specious form of renunciation dependent upon social capital and access. That freedom from stuff should even be the driving idea behind minimalism is equally illusory.

*

Last year, the reporter Kashmir Hill performed an elaborate experiment. Curious to see how difficult it would be to eliminate the presence of big tech in her life, she cut herself off from the “big five” (Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Apple). She bought a physical map and paid for things in cash. Switching to a Linux laptop and a Nokia phone, the simple task of sharing a digital file over email became a convoluted endeavor.

During Hill’s research, she conferred with Daniel Kahn Gilmor, an ACLU technologist and a “digital vegan,” who says his main concern is the ability for people “to lead autonomous healthy lives that they have control over.” He hosts his own email and avoids social media. He also acknowledges that while he has the privilege to make these decisions, others don’t.

“We need to think of this as a collective action problem similar to how we think about the environment,” he said. “Our society is structured so that a lot of people are trapped.”

The difficulty of escaping this trap is borne out in Hill’s reporting. When she attempts to use the internet without interacting with Amazon, she finds it’s “technically impossible.” Amazon Web Services (AWS), the largest source of profit for the tech behemoth, is the internet’s largest cloud provider, dominating huge portions of the internet by hosting an ever growing list of IP addresses. Hill’s experiment, which speaks to the ubiquity of big tech and the pervasiveness of digital surveillance, feels closely related to Chayka’s observations on our cluttered minds. At the end of her digital withdrawal, Hill realizes she’s dropped the modern habit of swiping for mindless amusement. She feels a greater sense of engagement with the world and the people in it, describing herself as “more in the moment.”

We want the world to be less complicated, but the aesthetics of superficial simplicity don’t provide an easy solution. If we are to live with minimalism in a meaningful way, it will need to be closer to Chayka’s idealized version—a minimalism that challenges us to attune our attention in order to “engage with things as they are, to not shy away from reality or its lack of answers.”

“Meeting” by James Turrell. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

“Meeting” by James Turrell. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

A more meaningful form of minimalism may look something like Odell’s reconception of resistance and attention, a framework that encourages us to pause rather than press forward, to nurture a world wherein one is provided the freedom and ability “to make oneself into a shape that cannot so easily be appropriated by a capitalist value system.” Maintenance over production, collectivity over individualism, real life over virtual reality. “When the pattern of your attention has changed, you render your reality differently,” writes Odell. “You begin to move and act in a different kind of world.”

Similarly, Mould advocates for a purposeful reorientation of society that resists co-option or appropriation. Rather than continuing to prop up capitalism, he champions a creative force capable of destabilizing its very foundation. A minimalism of import would do well to strive for a similar outcome; it may even be that engaging such a possibility is a prerequisite for minimalism to have any real meaning at all.

In mulling over minimalism as a conceptual framework capable of producing a new material reality, I think of moving. I recollect unpacking, emptying out all the boxes it seemed we had only just finished filling up. A big stack of broken down cardboard accumulated by the front door as we put our books on shelves and our kitchen junk in the kitchen (my desk is still a mostly unpacked mess). I thought of how the essence of moving is doing one long, involved thing forwards and backwards, and how this will very likely happen all over again. Settling in has a funny way of hinting at the inevitability of change, but rather than leading me to hope for more or long for less, it reminds me that life can move in different directions. Contained within this idea is a simple kind of equanimity, a feeling that can’t be commodified. For now, that seems like enough.

Andru Okun

Andru Okun is a freelance writer and editor living in New Orleans.