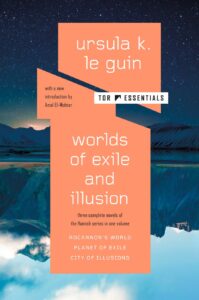

On Coming to Ursula K. Le Guin in My Own Time

How Amal El-Mohtar Fell Completely in Love

Ursula K. Le Guin’s 2004 collection of nonfiction, A Wave in the Mind, contains a curious, two-page essay titled “Being Taken for Granite”; punning on “granted,” she declares that she isn’t granite, she’s mud:

I am not granite and should not be taken for it. Granite does not accept footprints. It refuses them. Granite makes pinnacles, and then people rope themselves together and put pins on their shoes and climb the pinnacles at great trouble, expense, and risk, and maybe they experience a great thrill, but the granite does not. Nothing whatever results and nothing whatever is changed… I have been changed. You change me. Do not take me for granite.

I took Le Guin for granted. When she died in 2018, I could have fit the span of my life inside hers almost three times. She had always been there, like a mountain, or the sun, and it was easy to fall into the certainty that she always would be. I was unfamiliar with her most celebrated works—The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, books by which she became the first woman to win a Hugo Award for Best Novel, and then, five years later, the first woman to have won it twice.

I had assumed, with all the oblivious confidence of youth, that I’d get to read them while she was still with us and talk to her about them. I imagined that I would meet her one day, under ideal conditions that would make me seem interesting enough for conversation, and ask her about poetry, about being a middle-aged woman in the 1970s, and about science fiction. Her passing hit me harder than I expected, considering my slender acquaintance with her work, but that was the thing about Le Guin: to have lost her was to have lost a world I longed to visit.

I came to Le Guin’s work both early and late. On the one hand she introduced me to science fiction literature: I read “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”—Le Guin’s famous story about a wonderful city whose existence depends on the torture of a single miserable child—when I was perhaps eight or nine and far too young for it, in a neighbor’s ragged old edition of Literature and the Writing Process. I remember feeling keenly the difference between “Omelas” and everything else I read in the anthology: the colors brighter, the voice clearer, the ending a quiet explosion in the mind. I would return to “Omelas” every few years and find a different story there, and admire its capacity to unmoor my certainties and launch them in new, questing directions.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t read anything else of Le Guin’s until about a decade later, and I would read it badly, indifferently. I was introduced to A Wizard of Earthsea when I was eighteen, feeling like I was getting away with something by taking a contemporary fantasy literature course for which I could have written the syllabus. But in the late 1990s and early 2000s, wizard schools and Jungian shadows were all the rage, saturating all the comics and novels I was enjoying. In the cacophony of sorting hats and color-coded Houses, A Wizard of Earthsea seemed drab, boring—and I mistook as derivative work that was foundational. It would be still further years before I revisited Earthsea and found treasure in it.

I felt as if I was at last coming into alignment with Le Guin—that I was reading the right thing of hers at the right time to fall completely in love.

But shortly after Le Guin’s passing I read “The Day Before the Revolution”—a short-story prequel to The Dispossessed—and it shattered me. It’s the story of an old woman’s last day, trembling on the cusp of her life’s work bearing fruit while looking back at everything she denied herself to get there. I still can’t think of the ending without tearing up: “On ahead, on there, the dry white flowers nodded and whispered in the open fields of evening. Seventy-two years and she had never had time to learn what they were called.”

In one sense, I read this too late—too late to write to Le Guin and tell her everything it had made me feel, how much it made me want to live my life by its light. But in another, I felt as if I was at last coming into alignment with Le Guin—that I was reading the right thing of hers at the right time to fall completely in love. It was almost like a meeting: hearing her voice clear and true, speaking through an old woman’s mouth and ringing in my heart like a bell.

I’m now the age Le Guin was when she wrote Rocannon’s World, and I’m perversely glad that I still haven’t read her more famous novels. I intend to, of course—but I’m grateful to have now the opportunity of keeping pace with Le Guin’s books as she wrote them, to follow the path she blazed without knowing what comes next. To treat her, and her work, not as a mountain to scale or a sun to see by, but as a journey to begin; to take her, not for granite or granted, but as a cheerfully muddy road, fragrant and yielding and winding through the ferny brae, over the hills and far away, beyond the worlds we know and through those we mistakenly think we know well.

To have come to her work, not early or late, but in my own time—and to greet you here, fellow traveler, on the cusp of new adventure, whether or not you’ve passed through this work before, and to say to you, as we set out together:

Return with us, return to us, be always coming home.

__________________________________________________________

From the introduction to Worlds of Exile and Illusion by Ursula K. Le Guin, introduction by Amal El-Mohtar, published by Tor Books. Introduction copyright © 2022 by Amal El-Mohtar.Tor

Amal El-Mohtar

Amal El-Mohtar is an award-winning writer of fiction, poetry, and criticism. She won the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Awards for her 2016 short story “Seasons of Glass and Iron,” and again for her 2019 novella, This Is How You Lose the Time War, written with Max Gladstone, which also won the BSFA and Aurora Awards and has been translated into over ten languages. She is the science fiction and fantasy columnist for the New York Times Book Review. She lives in Ottawa.