On Channeling the Rage of Audre Lorde to Combat Racial Injustice

Myisha Cherry Balances Anger and Optimism in Navigating Systemic Oppression

Researchers have found that anger, unlike fear, elicits approach tendencies—a propensity to move toward an object rather than away from it. This happens specifically when we feel anger in response to goal frustration, goal pursuit, and the attainments of rewards. Racial justice is an example of such a goal or reward.

When anger arises, then, a person who has a goal—like racial justice—is likely to be eager to act. And it is the approach motivational aspect of anger that readies the individual to act in order to change the situation or remove its morally problematic components rather than run away from it. Audre Lorde was right. When we feel our goal of racial justice being frustrated, and experience anger in response to that, the object of our anger is change. We can see this all happening when we look at the brain.

Numerous studies in psychology and cognitive science locate anger in a specific region of the brain that is related to approach. Activation in the left frontal region of our brains is known to show an approach state, while activation in the right frontal region of our brains shows an avoidance state. For example, researchers created situations to induce either an avoidance or approach state in participants by inciting certain emotions. They used electroencephalograph machines to record where the high brain activity was occurring. First, to incite an avoidance state, they showed participants repellant films or presented them with punishments. When they did, researchers recognized that participants showed elevations of the right hemispheric activity associated with an avoidance state. However, when they presented participants with situations in which there were rewards, they noticed higher levels of left activation in participants’ brains. This activation showed an approach state.

We might think that negative emotions correlate with an avoidance state and positive emotions, an approach state. By positive emotions I mean emotions that tend to have a pleasant feeling and a positive judgment of its stimuli. Negative emotions have an unpleasant feeling and a negative evaluation of its stimuli. But when a person experiences anger (an assumed negative emotion), if the aim of that anger is a goal or reward, it activates high levels of activity in the left frontal parts of our brains, making us highly motivated to go after that goal.

Lordean rage, as a subclass of anger, has this approach-related effect. Although Lordean rage negatively evaluates wrongdoers and may not feel good when experienced, since it has a goal (e.g., racial justice), it makes the person with Lordean rage eager to do something about the situation— eager to approach rather than avoid it. And this eagerness effect has its benefits. When fighting against systemic problems such as racism, the task can be overwhelming. Systemic problems are powerful, often facilitated by powerful people. When the powerless decide to take on systemic problems, the task can seem too great; a person may feel too small, and that may provide reasons not to even try at all. But a person with Lordean rage is empowered by the motivation it provides to not retreat but to go forward to transform the situation. The power she is against may, in instances of fear, lead her to avoid challenging systems. However, the approach motivation that comes as a result of Lordean rage can lead her to approach her goal and obstacle. It makes her eager rather than discouraged to act.

Being eager to act is also important because changing any oppressive system is hard work. When the going gets tough, it’s easy to quit. But a person who is motivated to fight is more likely to keep pursuing her goal. This is also helpful in contexts of ongoing oppression. Racism is not a new phenomenon. It has a long history and is very much ongoing. When racial discrimination, mistreatment, and oppression are ongoing, a person needs fuel to keep fighting. Lordean rage, with its eagerness to approach its target and reach its goal, provides this fuel.

Optimism and Self-Belief

Anti-racist rage, as a subclass of anger, not only makes us eager to act to change the situation. It also impacts our attitudes. Studies have shown that anger makes people optimistic about future events. It also has this optimistic effect because anger influences our perceptions of control and certainty. To that end, angry people think that good things are going to happen and that they will prevail regardless of what happens. The reason is that anger triggers a bias into thinking that the self—the angry person—is powerful and capable. Interestingly, Aristotle alluded to this anger and optimism relationship thousands of years ago when he wrote, “For since nobody aims at what he thinks he cannot attain, the angry man is aiming at what he can attain, and the belief that you will attain your aim is pleasant.”

Optimism is important in the pursuit of racial justice. There may be instances in which you are fighting but are unable to see any sign of progress or change. In some instances, your efforts might achieve change; other times, not. Moral progress is not linear. It ebbs and flows. There could be moral progress one year and a rollback or backlash of progress the very next. (The election of Trump, a person who had engaged in racist behavior for decades, after the first Black president, Obama, seems to be an obvious example here.) It can be hard to be optimistic in such times.

But the upshot of Lordean rage is that it can make a person believe that he can still effect change even when all the evidence is against him. To engage in any fight, whether in a boxing ring or political campaign, you must believe in yourself. The belief that you can influence the situation—no matter how small, Black, or poor you are, or how many other intersecting, marginalized identities you may occupy—is important in any campaign aimed at transformation.

The optimism that is influenced by rage is not just restricted to attitudes and beliefs about yourself and your situation. Anger is also associated with optimistic perceptions of future risks. In other words, those who are angry—compared to those who are fearful—are more prone to make risk-seeking choices, and these choices are influenced by people’s beliefs about themselves. Angry people’s optimistic beliefs influence the risks they are willing to take.

I can understand this firsthand. Usually when I am angry due to goal frustration in my professional life, for example, those moments highly motivate me to do something particular about my situation. In response, I often take risks that I normally would not take if I was not angry. I often seek out opportunities that I would normally not seek out due to fear, lack of belief, or procrastination. And I do it knowing the risks involved (e.g., being rejected, putting myself out there). But my anger, in distinct ways, makes me want to risk it all, so to speak. We can imagine the ways this can go wrong. I could take unwise risks—and no doubt people often do, given this level of optimism.

Angry people’s optimistic beliefs influence the risks they are willing to take.

This fuel metaphor—made up of eagerness, self-belief, and optimism—helps explain the motivational role that Lordean rage has in anti-racist struggle. However, a person may still have a worry. If Lordean rage, as a subclass of anger, has this fuel, so do wipe, narcissistic, rogue, and ressentiment rage. What is then unique about this fuel as it relates to Lordean rage? Focus on that question misses the point. It’s not that Lordean rage offers a distinct kind of fuel. Rather, what’s special about Lordean rage is that it has the power to lead to distinct (positive) action. Revisiting the features of Lordean rage, as well as other kinds of anger that arise in response to racial injustice, can help make this clearer.

As we have seen, Lordean rage is a response to racism. It is not a response to “all white people” or to anyone who steps in the way of the outraged. The aim of Lordean rage is to bring about change—to create a world in which racial injustice is no more. Its action tendency is to metabolize it—that is, to make it useful for certain ends. The perspective that informs Lordean rage is not a selfish or hateful one; rather, it entails the notion that “I am not free until we all are free.” Given these features, we can begin to see how such rage can provide the fuel of eagerness, self-belief, and optimism that is necessary for positive action rather than the negative actions that so worried Seneca.

If one’s anger has an inclusive feature that focuses on justice for all and does not see any one person as an enemy, it is likely to fuel or motivate action that is directed at a lust for peace and equality rather than action that is (for Seneca) “raging with an utterly inhuman lust for arms.” If the object or goal is change and a just world, an angry person is likely to be greedy for a better social and political system—a world we can all live in together rather than being “greedy for revenge.” If the anger’s aim is to bring about radical change, it is likely to fuel action that seeks to end all slave systems rather than see “the persons of princes sold into slavery by auction.” And those who have this anger are likely to be eager to engage in these positive actions, optimistic about such engagement, and confident of their success. The anger I am describing that can do these things is Lordean rage.

However, if one’s anger focuses exclusively on destruction or sees everyone as the enemy, it is likely to provide an eagerness, self-belief, and optimism that will fuel or motivate negative action. A person with wipe rage is likely to make risk-seeking choices to accomplish the goal of elimination. A person with narcissistic rage is likely to believe that they can change the situation—a situation that only affects and thus benefits them, but not other oppressed people. A person with rogue rage is likely to think that good things will happen for him but not for others, and may engage in destructive acts to help produce that outcome. None of these problems occur with Lordean rage; unlike rogue, narcissistic, and wipe rage, Lordean rage lets us avoid these issues. This point is important for understanding how Lordean rage helps the outraged engage in anti-racist struggle.

“Focused with precision, [Lordean rage] can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change.” This rage has the energetic potential to inspire and spark action directed toward what Lorde calls “a basic and radical alteration in all those assumptions underlining our lives” rather than “a simple switch of positions… [the] ability to smile or feel good.” Things don’t always go according to plan. Lordean rage can become useless when it fails to fuel positive action. While it often fuels positive change, it doesn’t always succeed in doing so. (In Chapter 6 I provide anger management techniques—inspired by Lorde and others—to help ensure that Lordean rage achieves its goal.) But for now, it’s simply important to see all the ways in which Lordean rage has a deep, unique potential to inspire us to take positive action. Then it’s up to us to use it in the fight for what is right.

__________________________________

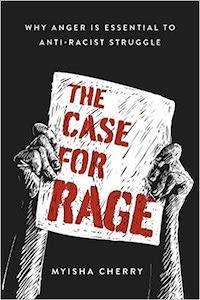

From The Case for Rage by Myisha Cherry. Copyright © 2021 by Myisha Cherry and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Myisha Cherry

Myisha Cherry is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Riverside. Her books include UnMuted: Conversations on Prejudice, Oppression, and Social Justice, and, co-edited with Owen Flanagan, The Moral Psychology of Anger. Cherry is also the host of the UnMute Podcast, where she interviews philosophers about the social and political issues of our day.