On Anne Frank, Oskar Schindler, and Writing a Documentary Novel

Buzzy Jackson Recounts the Road to Writing About Hannie Schaft

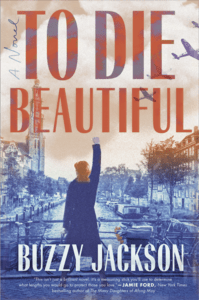

Although it’s not really possible to accidentally write a novel, it sometimes feels that way to me. To Die Beautiful, my debut novel, tells the story of Hannie Schaft, a quiet Dutch college student who, when Germany occupied her country in 1940, somehow left the shy, studious girl she had always been behind.

She quit school, the only thing she’d ever been good at, and began committing small acts of sabotage, then joined the Dutch resistance movement and immediately learned how to use a gun, plant bombs, and transport weapons across the country in the basket on the front of her bicycle.

By 1944 she had become a full-time assassin of Nazi officers and collaborators and although Adolf Hitler didn’t yet know her name, he sent word to his lieutenants in the Netherlands to find and capture her, “the girl with the red hair.” This is a true story. And Hannie Schaft and most of the other main characters in the book were real people; some were still living among us until just a few years ago.

Slowly I grew more confident in my ability to understand the time, place, and people of that era.

Although every English major probably believes, deep down, that she might be a novelist, I never allowed myself to say it out loud. I was so intent on not being a novelist that I switched to History in graduate school. I put that training to work as an author of nonfiction books, writing about topics that interested me: Bessie Smith, DNA, my own overexcited wonderment about our place in the universe.

I thought I’d continue to do that sort of thing right up to and even after I first learned about Hannie Schaft. She was amazing, yet almost as incredible was the fact that there were so few recent books written about her, at least in English. So I decided to write one. But a novel? Never crossed my mind.

That changed once I began the research. I’d first learned of Hannie’s story in the winter of 2016-2017 on a visit to Amsterdam, where the Verzetsmuseum (Museum of the Resistance) featured a small display about her resistance work. Almost all the archival material relevant to her story was not only written in Dutch but was kept in the Netherlands.

I don’t speak Dutch, nor do I live in the Netherlands, but fortunately a number of generous friends and colleagues there helped me with translation, cultural context, and a place to stay when I visited for research trips. Slowly I grew more confident in my ability to understand the time, place, and people of that era.

The most well-known tale of the Dutch Holocaust is the story of Anne Frank and her family, hiding in the attic of an Amsterdam warehouse. The whole world knows their story thanks to the sensitive, beautiful writing of the teenaged Anne Frank, the determination of her father, Otto Frank, to get it published, and of course the document itself: Anne’s diary. Everything we know about Anne Frank’s inner life can be found in the pages of that little book. For a historian, a personal journal like hers is the ultimate primary source, the rare window into a private, endangered life.

“I want you to know that I’m planning on telling this story in the form of a novel,” I said nervously, wanting to be as transparent about my own goals as possible.

Hannie Schaft, however, never kept a diary; as an underground resister, it would have been foolishly risky to do so. There were a few letters she wrote to friends and family, some political science essays she wrote in high school, and the recollected conversations she had with the people she loved. But no direct account of how Hannie felt as she, like Anne Frank, watched her country descend into horror.

It was my agent who first suggested I consider writing Hannie’s story as a novel. I was skeptical, at first. It was probably the academic training I’d received as a doctoral student, but I was reluctant to turn Hannie’s real life into fiction. Nevertheless, as with previous book projects, I began looking for a pre-existing model of what I was considering, to see if it was even possible.

The first thing I noticed was that most of my models were not books at all, but movies. There are thousands of films about historical subjects that are not documentaries, from All the President’s Men to Dunkirk. In cinema there exists an established category for films that hew to the reported facts of a historical moment while not guaranteeing every single spoken word can be footnoted. And this was my central problem: without fictionalizing parts of Hannie’s story, my book would contain virtually no dialogue.

No nervous conversations between Hannie and her Jewish friends, Philine and Sonja, as she made plans to hide them in her family home. No confrontations between SS members and Hannie in disguise, trying to get past armed guards at a checkpoint. Without some amount of imaginative recreation, I realized, the emotional intensity of her story might never come to life.

And then I remembered Schindler’s List. The book, by Australian author Thomas Kenneally, was published in 1982, telling the incredible story of German industrialist and Nazi Party member Oskar Schindler’s improbable decision to save as many Jews from the Nazi death machine as he could. Many readers (and, later, movie watchers) accept Schindler’s List as a nonfiction account of the Holocaust. Yet Kenneally described it as “a sort of documentary novel … a writer using something of the tone to tell a researched story.”

He, in turn, cited yet another book as his model. “The book is fiction in the sense that Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff is fiction,” he explained. “The facts are there, but I make use of fictional techniques in character development, the manner in which an incident is relayed…some fictionalization when there is not a record of the dialogue.”

This revelation gave me courage, mostly because Kenneally was also candid about his own doubts about taking it on. An Australian citizen with Irish Catholic roots, what he knew about Jewish people was “chiefly from books: Roth, Malamud, Bellow.” Kenneally confessed these doubts to Leopold Page (né Pfefferberg), the Holocaust survivor who introduced him to the story and urged him to write it.

“An Australian is perfect to write it,” insisted Page: “what should you know? You know about humans.”

Above all, Kenneally was moved by the story of Oskar Schindler and the Jews who survived and wanted their stories to be remembered. I felt the same way about Hannie Schaft, her courageous Jewish friends Philine Polak and Sonja Frenk, and her valiant colleagues in the Dutch resistance, the young sisters Truus and Freddie Oversteegen, and comrade Jan Bonekamp. Their stories–true stories–were too important not to share with as wide an audience as possible.

And so I began, hesitantly and carefully, to craft a tale of their incredible bravery, terror, and hope in a lightly fictionalized format. I still remember interviewing the daughter of one of the Dutch resistance fighters. “I want you to know that I’m planning on telling this story in the form of a novel,” I said nervously, wanting to be as transparent about my own goals as possible. She laughed. “I think you have to!” she said. “I doubt anyone would want to read it, otherwise.”

I never intended to write a novel. But, as Thomas Kenneally discovered, sometimes a story finds you, and then challenges you to tell it. Hannie Schaft’s story brought to life a chapter of history that I thought I understood but in fact was completely new to me, a surprising story of young women resisting the forces of hatred, bigotry, and racism that can teach us so much about the world we live in today.

Out of respect and admiration for the real people who lived it, I tried to stay as close to the facts as possible. But out of a desire for readers to meet and understand these incredible real-life heroes, I finally became a novelist.

__________________________________

Buzzy Jackson is the author of To Die Beautiful, available from Dutton.

Buzzy Jackson

Buzzy Jackson earned a Ph.D. in U.S. History from UC Berkeley, where she wrote her first book, A Bad Woman Feeling Good: Blues and the Women Who Sing Them. She has received numerous writing and teaching awards, including those from UC Berkeley, PEN-West and the American Library Association. She is currently a Research Affiliate at The Center of the American West at CU-Boulder. Buzzy writes for many online publications as well as for radio and film.