My marriage lasted exactly nine days, making waves in our tiny, riverine country and setting me adrift for the rest of my life.

It started with my extended family, when I knocked on my parents’ door that ninth night to wake them.

It was raining, heavy and overbearing, and as the roof of our home was fairly flat, the sound of my knuckles rapping on the wood didn’t travel inside: it was, instead, immersed in the beat of the falling rainwater. Dead silence filled the house.

My hands hurt, more than my head and my stomach, and I was soaked through. And scared, not only of the ominous graveyard nearby that the lightning transformed into an even more nightmarish setting, but also of the city’s overall bleakness when asleep, this city that let itself be vanquished by water. Scared of my mother and father’s house, which was refusing to let me inside on my flight to the odors of talcum powder and brass polish, tobacco and old newspapers, which would get rid of the smell of blood hanging around me.

I didn’t merely knock again but pounded hard on the door and shouted. As if laughing at me, the water and the wind carried the sound of my pleas back to my ears.

Pain! Pain!

Behind me loomed The Other Side.

*

Irritated but relieved, I stood, moments later, in the dimly lit kitchen, wondering how long it had been since I’d climbed inside through the swollen window that didn’t fully shut, but the memory faded suddenly against the urge to burrow into my mother, as quickly as I could, as deeply as I could. Warmed by this prospect, I hungrily sought my parents’ room. Solemnly, I laid my hand on the marble doorknob, turned, pushed.

Years later, I’d understand: through that door I passed the threshold into pain.

*

When I was young, they said I was a beautiful child. Moi misi, they’d exclaim, those women in their pleated skirts, hugging me so close that my head rested on their bellies. Some of them smelled of fresh fish, but sometimes a putrid smell of rot wafted up my nose. I’d groan and pry myself free.

“Noenka, Noenka,” they’d say, trying to coax me out, but I’d stay under the bed until my mother came and enfolded me in her lap: clean, warm, and safe. There were some aunties I liked, simply because they didn’t spread their thighs to welcome me but sat down next to me on the sofa with their legs crossed.

They spoke a soft sort of Dutch and wore skirts in solid colors with velvet bodices and skinny belts. Their legs shone like silk through their nylon stockings, and their dark shoes squeaked.

Ma didn’t entertain these women in the kitchen, and she poured tea in dainty blue Delft cups and offered slender, golden-brown wafers.

While they chatted about their virtuous daughters, their intelligent sons, their lazy housemaids, and the ladies’ charity circle, I caught the whiffs of perfume they released with every move. I listened to them chatting about a church bazaar to raise money for a new desk for the minister, a kind, friendly man with a darling blond wife, then asking whether Mrs. Novar, as usual, would supply all those delectable little snacks and that downright divine cake from last time.

My mother blushed, I snuggled up against her with pride, and she said “yes-of course-gladly” and urged the ladies to take home a slice of pie, neatly wrapping the wedges in no time flat and then presenting them to her guests in a silver box. But as we waved goodbye to them, she loudly sucked her teeth: she beat the throw pillows back into shape and ate—with my help, one after the other—all the remaining wafers, those conventional offerings dictated by courtesy.

“Are you angry?” I asked, tongue thick with cookie crumbs.

“Not angry.” She smiled, squeezing me tightly against her.

*

When the sun rode so high I was stepping on my own shadow and Ma was bringing in the bath towels, she came bobbing along. I ran to the gate, scratching myself on the rough wooden latch again, but joyfully I took her outstretched hand.

Peetje smelled like overripe sapodilla and bananas, and she chewed indifferently on a bitter orange stem whose scent stung my nose and made me sneeze. She stood there, her outspread hand on my head, as I filled my mouth full of strange sweets from the colorful jars nestled in the wooden crate she carried on her head.

As I jumped up and down amid the folds of her skirts, my shoulder bumped into her petticoat, its heavy pocket filled with coins, so many coins, to me a fortune that no one else’s could rival.

On the back porch of our house, she groaned as she set down the crate and talked to my mother in a lilting language that meant little to me. They drank ginger ale with ice cubes and ate fried fish. Their abundant laughter came often: Ma’s piercing and full, Peetje’s low and ample.

And I, hopping from one lap to the other, hoped that Peetje would never leave.

She’d always grumble when she left, the crate on her head, the layered skirts of her traditional koto dress stiff and full around her wiry body. I saw her off, waving until the sunlight burned my eyes and a whirlwind of school children sent me running scared into the house.

Apples. Nothing but apples, light pink with white bottoms that did no more than quench your thirst unless dipped in salt; deep red apples that brought to mind the angry pouts of old disgruntled aunties but tasted all the sweeter; and colorless ones so delicious that lines of black ants made an endless journey from their nests to the high branches, forcing their way into the cracks.

The apples turned ripe all at once. Each morning, they lay in the dark backyard by the hundreds, and they kept falling, the whole day through.

It was mid-May…

The usual pale blue of the sky was marred daily by shapeless rainclouds that pushed in from the east. Then something in the greenery shook, the wind grew damp, and within no time, there was nothing but water. And apples. Among the shimmering leaves, they hung quivering in tight clusters, those that didn’t fall and burst like firecrackers.

I was staying at Peetje’s, loaned out by my mother to help alleviate the apple crisis. All day I did nothing but collect apples, rinse away any ants and mud, and heap them in a fairy-tale pile. An impressive pastime for a six-year-old crazy about anything sweet and colorful.

Emely, Peetje’s only child, stood in the kitchen stirring an assortment of pots with wooden spoons.

After a couple of days, she had such a collection of filled jars that even the best-stocked Chinese shop couldn’t compare. I helped take the jars to Uncle Dolfi, who, under a metal lean-to, traded in practically everything ordinary people needed in small quantities. He built two extra shelves and stocked them full of apple jam, apple compote, apple cider vinegar…apple this, apple that.

I got the greatest sense of satisfaction, however, from announcing the customers with their rusted pennies to Peetje, earning myself toys, candy, and colorful shards of broken glass from them for the work.

Still, I never gave even one apple away in secret. Instead, I helped make Peetje’s purse heavier. Tired from collecting apples, I’d fall asleep in her arms before dusk.

__________________________________

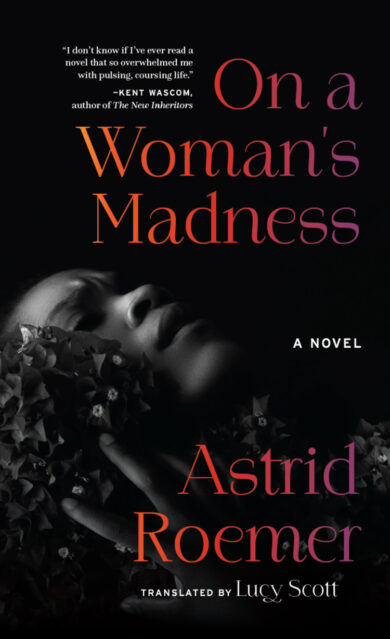

From On a Woman’s Madness by Astrid Roemer (translated by Lucy Scott). Used with permission of the publisher, Two Lines press. Copyright © 2023 by Astrid Roemer/Lucy Scott.