I woke to several different noises, something being picked up and put down, a tap being turned on and off. What time is it? I said. It’s 4 a.m., said Mim. For a moment she was silhouetted in the bathroom door before the light went off and she was reabsorbed into the dark. Outside, the sky was so black that when I looked at it I was looking at nothing but my memory of the sky. Were it not for the moon shining through the narrow band of windows, I couldn’t say whether my eyes were closed or open.

The church bells rang four times down in the bay. I stuck my foot out from under the covers and tried to sleep, but my head was full of nighttime voices overtaking and interrupting one another so it sounded like there were many voices talking at once though really it was just the same voice repeating the same few meaningless questions—What month is it? Clytemnestra? Who was Tchaikovsky’s son?—which, in any case, were impossible to answer since each one seemed to dissolve the moment it caught my attention.

Lying there, the quiet was disturbed by the sound of Mim’s footsteps toing and froing on the ceiling above me. You’re too sensitive, said a voice inside my head. It’s just Mim, walking. So I rolled over and closed my eyes but on my side the sound of her footsteps dropped down in a straight line from the ceiling into my ear where, having penetrated my head, they made a right turn and took root in my sternum before infecting my heart, which started beating louder and faster than before. Relax, I told my heart, there’s nothing to worry about. But of course a heart doesn’t understand human language and the only way to still it is by force, which I did, wrapping my arms tightly over my chest, though each time I drifted off my grip relaxed and the thudding, unsuppressed, would startle me awake again. Don’t just lie there, the voice said. Why don’t you do something? Why don’t you find her and ask her what the matter is?

Because sometimes, I thought, it’s better not to know.

I must eventually have grown immune to Mim’s pacing because the church bells rang five times in the bay but by six o’clock they’d been incorporated into a dream in which I, in a concert hall, was about to premiere a concerto by a celebrated composer. The orchestra had already started but I was waiting for the conductor to bring me in, which presently he did, gesturing at me with his baton. I put my hands on the piano but when I looked up at the score all I saw was a jar of peanut butter. The next page had no musical notation either, just more pictures of peanut butter. Don’t just sit there, the conductor hissed. Do something! So I took my hands off the piano again and said, Peanut butter. And then, because what else was there to do, I said, Peanut butter again. Peanut butter, peanut butter, peanut butter . . . I said. And the orchestra, lowering their instruments, started chanting, Peanut butter, peanut butter, peanut butter . . . too.

“Relax, I told my heart, there’s nothing to worry about. But of course a heart doesn’t understand human language and the only way to still it is by force, which I did, wrapping my arms tightly over my chest, though each time I drifted off my grip relaxed and the thudding, unsuppressed, would startle me awake again.”

The mood of foreboding left over from the dream dissolved the moment it was exposed to the pitiless light flooding through the bedroom windows. I pushed past the moldy blue plastic curtain separating the bathroom from the bedroom, went to the toilet, and felt empty. It was only eight o’clock—the church bells rang eight times in the bay—but I felt disoriented, as though I’d slept right through the day into the following night. The remains of Mim’s bathwater were lukewarm, neither hot enough to be comforting nor cold enough to jolt me out of the fog of oversleeping.

I pulled the plug and the pipes behind the house shuddered and moaned as they drained away the gray water. Like everything in the house, the blue mosaic bath was a replica of the one in the Villa Savoye. The house was one of three Villa Savoye doppelgängers: there was the “shadow” version in Canberra, which was an exact copy but painted black; the “mini” Villa Savoye in Boston, in which every aspect of the original had been shrunk by 10 percent to fit the client’s budget; and my house, the House for the Study of Water, which replicated Le Corbusier’s in all aspects apart from its location since the original Villa Savoye overlooks the rural French landscape, while the one in Cape Town overlooked the sea.

Everything I knew about Le Corbusier came from a South African academic who, like a number of so-called architourists, had turned up at the house one day as though it were a museum rather than a private residence. She wore a kaftan and jangly bracelets and was writing a book, she told me, on Le Corbusier and the “third world.” The architect who’d designed the House for the Study of Water, Jan Kallenbach, had met Le Corbusier during a tour which he and several other architecture students had made of European architecture. They’d turned up at Le Corbusier’s apartment one day, she said, and the old architect had invited them in and said, OK—she mimicked his French accent—so now I will teach you the système. The système entailed a number of rules which Le Corbusier applied to all buildings, regardless of their size or use, like that all buildings should have movable walls, a roof terrace, horizontal windows and be raised off the ground on stilts. The architecture students—later known as the Johannesburg Group—published articles on Le Corbusier’s système in the local journal, South Africa Architectural Record, and applied it to the design of a number of new houses, built mostly for German Jewish immigrants who’d developed a taste for modernism before the war. With their glass walls and external staircases, these houses typified what became known as the Johannesburg Style. The point about the houses, she said—this must have been important because she repeated it several times—is that they were “à la Corbu” but not just meaningless copies. They took his system and synthesized it in a new way. Whereas Kallenbach, apparently, had been so seduced by the Master, as he’d called him, that he believed the practice of architecture post–Le Corbusier could offer nothing more than to replicate his buildings verbatim. We were standing at the strip of windows in the living room, looking at the sea. That’s why he was ostracized from the inner circle, she said. Then she turned away from the window. I feel queasy, she said. The way these windows cut off the ground makes me feel seasick. And for a moment she did look pale, but then, laughing, went on. Maybe that’s the reason Kallenbach’s wife left him. Because living here was like living on a raft. It’s true, the windows did give one an odd perspective of the world. I’d often thought it perverse that a house overlooking the sea should have windows so narrow that they hid all but a sliver of it. It was a restrictive view, almost punitively so, so frustratingly partial that it seemed a kind of tease. Though the sense of something withheld—the sea was there, of course, you just couldn’t see it—was not entirely unpleasant.

__________________________________

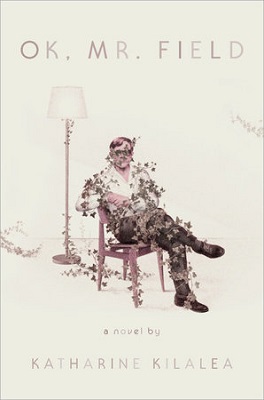

From OK, Mr Field. Used with permission of Tim Duggan Books. Copyright © 2018 by Katharine Kilalea.