Of Willa Cather’s Lasting Love For the Frontier

"I Do Think My Heart Never Got Across the Missouri River.”

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of My Ántonia. Today, the Willa Cather Foundation is celebrating the author’s 145th birthday with a community open house and cake at the National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud, Nebraska. The farm community of Webster County has defined much of Cather’s work and life; she often returned to her childhood home in Nebraska to visit family and friends.

Here we look back on that year, a century ago, that was so pivotal to the author and her world.

*

1918 began with a harsh blizzard and below-zero freeze that seized the Hudson River. The flu pandemic was to sweep the country and the world, propelled by the movement of the Great War which ended on November 11 that year. Living in New York City, Willa Cather and her partner Edith Lewis grappled with a coal shortage, frozen pipes, and illness. Cather bemoaned to her sister-in-law Meta that her pursuit of a reliable fuel source had made it almost impossible to keep up with her work. “If I can’t get my book finished by the first of March,” she wrote, “both the publisher and I will lose money.” Cather was referring to My Ántonia—a work that would become her most beloved and acclaimed novel.

The woes of winter, a bout of bronchitis, and the illness of her cook Josephine all delayed the spring publication of the novel. By early February, Cather was full steam into editing but insisted to her publisher that the book would be better for not being rushed. With Cather’s persistence, the book was published in September.

This photo was taken Dec. 7, 1936, on Willa’s 63rd birthday by H. Foster Ensminger. This photo is from the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial collection. © The Willa Cather Foundation

This photo was taken Dec. 7, 1936, on Willa’s 63rd birthday by H. Foster Ensminger. This photo is from the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial collection. © The Willa Cather Foundation

My Ántonia is Willa Cather’s hymn to the prairie and the American frontier blazed by an influx of immigrants from Bohemia, Germany, Poland, and other eastern European countries. It is the story of Ántonia Shimerda’s life narrated by her childhood friend, Jim Burden, and closely hews to the story of Anna Pavelka, a Bohemian immigrant to Nebraska. As a child, Cather lived just two houses away from the Miner House where Anna was employed. It was Anna’s strong character and spirit that most attracted Cather, and in one later interview she described her friend as “big-hearted and essentially romantic” despite her often difficult life.

“A man in The Nation writes that ‘My Ántonia exists in an atmosphere of its own—an atmosphere of pure beauty.’ Nonsense, it’s the atmosphere of my grandmother’s kitchen, and nothing else.”Cather lived in New York for most of her life, but it was to Nebraska that she always returned. A 1921 interview with the Omaha World-Herald noted that “Miss Cather is just that homey sort of a person who loves her friends—not social acquaintances—but friends. That’s why she has been coming back each year to Nebraska to visit her father and mother and her friends—to see the people and the things with which she is familiar.”

It was that intrinsic familiarity with the Great Plains and its people that prompted New England writer and friend, Sarah Orne Jewett, to encourage Cather to write about her childhood world. “You have to know the world so well before you know the parish,” Jewett advised, according to the Omaha World-Herald.

The Pavelka Farmstead. Photo by Catherine Pond

The Pavelka Farmstead. Photo by Catherine Pond

In late summer, Cather arrived in Red Cloud for an extended stay. She often visited Anna Pavelka at her family farmstead north of town and those visits, such as one in 1916, inspired Cather to include beautiful descriptions of the farmstead at the end of My Ántonia.

Cather wrote about domestic scenes the way a Dutch painter portrays an interior—whether it was putting up food, making kolache, or the “fruit cave” of the Pavelka farm. These quiet, often unnoticed backdrops and rhythms of daily life, gardening, and natural landscapes always framed her narratives, especially her prairie novels. On Thanksgiving Day, Cather wrote to her brother Roscoe: “A man in The Nation writes that ‘My Ántonia exists in an atmosphere of its own—an atmosphere of pure beauty.’ Nonsense, it’s the atmosphere of my grandmother’s kitchen, and nothing else.”

A century later, My Ántonia remains perhaps Cather’s most enduring work, with its poetic descriptions of the people and places of her childhood, the challenges and toils of farming, the presence of the prairie as its own great and often mystifying force, and the cultural relevance and history of immigrants in the American West. Against that backdrop emerged the determined character of Ántonia, an unwitting feminist who could easily be a modern response to the political issues of today.

The Willa Cather Childhood Home, a National Historic Landmark. Photo by Catherine Pond

The Willa Cather Childhood Home, a National Historic Landmark. Photo by Catherine Pond

A few years before the end of her life and at the peak of World War II, Cather received a fan letter from Harrison T. Blaine. He and his family had lived for a time at High Mowing, a hilltop farm in Jaffrey, New Hampshire near Mount Monadnock. Cather often pitched a tent in their large pasture where she wrote much of My Ántonia on her first of many annual visits to the Shattuck Inn in 1917.

“This letter is the result of an impulse which probably in a sane moment I would repress,” he gushed, and continued:

“Last night I finished reading My Ántonia for the third time in my brief life. I want to tell you how much I enjoyed it, what a splendid character you have created in Ántonia, what a warm picture you give of the seasons and land of Nebraska, and what a masterpiece I believe it to be. I have read quite a number of your other books but none seems to me to have the sweep of My Ántonia. … There has been much talk of the American Dream. For me it is the peopling of the whole world with men and women like Ántonia. It is perhaps farfetched, but I feel that the basic cause for which we fight is to make such a thing possible.”

Cather often fretted that her books would not be well-received by the communities that she wrote about, but was relieved when she received letters from many immigrant families after the publication of My Ántonia. The novel was so popular among the Czech community that it was even translated into Czech along with dozens of other languages.

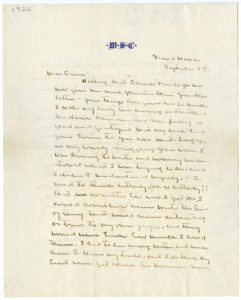

Willa Cather’s 1922 letter to Carrie Miner Sherwood. © The Willa Cather Foundation

Willa Cather’s 1922 letter to Carrie Miner Sherwood. © The Willa Cather Foundation

In an interview with Latrobe Carroll of The Bookman in 1921 Cather elaborated on the inspiration to write about them:

“When I was about nine, father took me from our place near Winchester, Virginia, to a ranch in Nebraska. Few of our neighbors were Americans—most of them were Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, and Bohemians. I grew fond of some of these immigrants—particularly the old women, who used to tell me of their home country. I used to think them underrated, and wanted to explain them to their neighbors. Their stories used to go round and round in my head at night. This was, with me, the initial impulse. I didn’t know any writing people. I had an enthusiasm for a kind of country and a kind of people, rather than ambition.”

With My Ántonia published, Cather began to prepare her next novel. While in Red Cloud that autumn, she read her cousin G.P. (Grosvenor Phillips) Cather’s correspondence back home from the front lines of World War I. He had died in France that spring, on May 28th, at the age of 34. Moved by G.P.’s death, who would inspire the character of Claude Wheeler, she began work on One of Ours, which won her the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1922.

“I had to live among writers and musicians to learn my trade, but I do think my heart never got across the Missouri river.”From the island of Grand Manan, Canada, in September 1922, Cather wrote to her childhood friend Carrie Miner Sherwood. She included a mention of the character of Claude and her love of her family and friends on the prairie:

“Long ago, in my lonely struggling years when I was learning to write and nobody understood what I was trying to do, and I didn’t understand myself, — I used to think bitterly, (oh so bitterly!) that no matter how well I got on, I could somehow never write the kind of thing that would seem interesting or true to my own people, and they would never know how much I loved them. I had to live among writers and musicians to learn my trade, but I do think my heart never got across the Missouri river. And now you do all know, after all — at least those of you I love best know. Claude and his mother are the best compliment I can pay Nebraska.”

Willa Cather died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 73 on April 24, 1947 in her home that she shared with Edith Lewis at 570 Park Avenue in Manhattan. She was buried a few days later in Jaffrey, at her request and through Lewis’ arrangements with local friends (for the burial ground has always been considered for Jaffrey residents only).

While Jaffrey was where Willa Cather said she wrote her best work and chose to be buried, she could never shake Red Cloud. Centered just 15 miles north of the exact geographic center of the lower 48 states, Red Cloud is where Cather believed she was her most authentic self: “I always come back to Nebraska.”

*

Images and a selection of letters © The Willa Cather Foundation, a non-profit organization in Red Cloud, Nebraska that promotes the legacy of renowned author Willa Cather through education, historic preservation, and the arts from the National Willa Cather Center, opened in 2017. The foundation operates over ten preserved historic buildings, historic landmarks, and landscapes—open to the public for guided tour—that were lived in by family members or shaped the settings in much of her writings, as well as a 600+ acre memorial site of untouched prairie on the Kansas border.