Notes on Camp: Caitlin Cowan on the Joys of Working With Young Writers

“Play and experimentation should drive the young writer’s work, and all of our work.”

“The rolling, appreciating laughter of the audience at Spirit-in-the-Woods had cured her of the sad year she’d just gotten through. But it wasn’t the only element that had cured her; the whole place had done that, as though it was one of those nineteenth-century European mineral spas.”

–Meg Wolitzer, The Interestings

*

Last summer, a young student in my summer camp creative writing class raised her hand to ask me an important question: “What does an owl smell like?”

My poet’s brain swiveled toward her like a flower toward the sun. It was a moment that assured me I was in the right place at the right time. Her question is characteristic of the magic of working with middle- and high-school writers. Such longing to know drives students’ writing development forward in organic ways. Her fresh eye (and nose) were instantaneously instructive. I began to answer her question aloud while greedily hoarding my words for later: trees, dust, nighttime.

While questions like these sometimes come up in higher-ed creative writing workshops, most of the class time is spent on more nuanced craft questions. And it’s almost embarrassing to talk about the even “deeper” stuff. But at Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp, where I serve as the Chair of Creative Writing, the deep stuff about what it means to be a writer and the mystical questions of imaginative experience—the owl smell—are front and center, and working here full time has transformed my writing life, and my writing, for the better.

*

A uniquely American creation, summer camp has withstood our best attempts to warp it into a bootstrapping acculturation machine and remains one of the few “third places” where young people can explore, play, and grow in an environment that isn’t manacled to achievement. The first summer camps were far from utopian: their founding, like most American institutions, was rooted in whiteness and exclusion, and cultural appropriation of Native American language, motifs, and practices is an ugly legacy that some camps are still reckoning with.

Spending time with young writers…has helped to restore my natural impulses as a writer.

Throughout history, summer camps have often reflected the mores and anxieties of their age. During the Industrial Revolution, camp was a place for children to experience the outdoors at a time when factory work was on the rise, but they also aimed to counter supposed “feminizing” forces in the home.

These days, many camps have no-cell-phone policies designed to help students “look up” from their glowing phone screens. The best summer camps, like mine, cater to students of all genders, races, and backgrounds and think hard about equity and access for all. And as any diehard summer camper will tell you: camp can be life-changing.

*

At the most profoundly unhappy juncture of my life, burnt out a bad relationship, broke from teaching on nine-month contracts at a university, and profoundly missing the color green after nearly a decade in north Texas, I took a summer job teaching writing at Interlochen Arts Camp at the urging of a dear friend and fellow writer. Those eight weeks reintroduced me to my native Michigan in all of its verdant majesty and to the secret alchemy of summer camp: trees, music, sweat, friendship, discovery, transcendence. I began to remember what summer camp meant to me, and who I was when I was there.

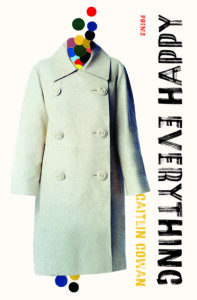

From 1999–2003, I attended Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp in Twin Lake, Michigan, and later toured with their international program as a violinist. That camp was and remains my childhood happy place. In my debut collection of poetry, Happy Everything, summer camp functions as a locus of both initiation and agency in “My Father Drives to Muskegon with a Bouquet of Flowers.” In this poem, the speaker’s estranged father listens to her summer camp symphony concert, which he has attended unannounced.

The poem, like much of the book, is inspired by my lived experiences. At a time when my nuclear family was imploding, my cabinmates at camp became like a second family to me. I found community and began to grow my faith in my strength as a young artist at Blue Lake. And so, when fate dropped a job posting for a full-time position managing their international program into my lap while I was more or less up the road at Interlochen, I leaped on it with the kind of zeal reserved for on-screen kisses and lottery wins.

I learned that the camp was interested in me not only as a program alum but also as someone who could build a creative writing program: the only artistic discipline without a true course of study at Blue Lake. My heart warbled a long-forgotten tune; I got the job. But that meant I had to move across the country and leave higher education.

*

Stepping back from academia and into a more democratic artistic space at a nonprofit liberated me from the precarity of contingent faculty teaching and changed my writing. Proximity to the energy and verve of younger writers, the freedom to teach outside of hierarchies and rigid assessment alongside artists from other disciplines, and daily immersion in nature and the offline world—to say nothing of the stable working conditions—have made me a better writer, one who’s working closer to the bone creatively without depleting my own creative energy as quickly as I used to. I’m braver: I think about what my poem could offer someone who isn’t a poet themselves. I write in my truest voice, not the voice of my innumerable male professors. I let the natural world in more. I open the window.

Writers in grades 7–12 are not squarely focused on craft: many are seeking confirmation of their right to speak, support for their unique voices, and advice about what it means to be an adult creative writer. Getting to answer these questions feels sacred. They constantly ask, “Can I ________,” where the blank represents almost any creative impulse they have. “Can I break lines like this? Can I write about this subject? Can I do an erasure of the Blue Lake camp catalog?” they ask. Every time I shout YES in response to their questions, I’m saying yes to myself, to giving myself permission to do and try and be my own weird self on the page.

Thanks to my time spent developing a creative writing program for young people, the most important tenet of my pedagogy now is play. Play and experimentation—which is play with its lab coat on—should drive the young writer’s work, and all of our work, really. The professionalization of creative writing since the 1950s and the proliferation of creative writing MFA programs have tempted writers away from the mess of play and toward the “seriousness” of writing as work. But you can always tell when a writer has stopped experimenting, can’t you? When it’s all work and no play?

*

My work (and play) at Blue Lake has asked things of me that I never would have confronted had I parked myself in higher education forever without seeking experiences elsewhere. I’m able to offer unusual teaching experiences to faculty I hire for the creative writing program as well. When I interview prospective faculty, candidates often ask for the gritty details of my pedagogical requirements. They’re pleasantly surprised when I ask them, “Well, how do you want to teach?”

And this isn’t laxity: it’s conscious design. At Blue Lake, we get to retain all the best things about traditional educational settings while jettisoning the things that hold educators and, importantly, students, back from learning and connecting with their art forms more deeply. There’s no assessment beyond a narrative from faculty that goes home with students at the end of the summer, offering a word or two of gentle critique sandwiched between toothsome layers of praise for their growth, passion, commitment, and attitude.

We create a final class anthology and hold a session-end reading for students to showcase their work. We don’t have a computer lab. Sometimes students don’t even use desks—we wander the forested campus with notebooks and pencils, stopping along the way to pen ekphrastic works based on a cello sectional, dance rehearsal, or ceramics firing we witness or are directly involved in as collaborators.

How deeply I wish such a program had existed for me in 1999. Back then, violin took center stage at camp while I penned poems instead of listening during math class at school. When I taught creative writing at the university level, I began to develop an interest in the question of how creative writers were made.

Working at a summer camp with young writers took me back to poetry’s roots and forced me to question the assumptions I held about the art form.

What I’ve found is that most young writers are like I was 25 years ago: secret scribblers who read a great deal and wrote without much tutelage save a motivated English teacher or two who would write supportive notes in the margins of their required compositions.

While programs to develop young people in other artistic disciplines are plentiful, programs for young creative writers are much rarer. We wouldn’t expect a violinist to begin learning her instrument without a teacher, but we find that writers are often born sui generis, emerging from the primordial ooze of what they’ve read and a desire to create that comes from…well, from somewhere else. Somewhere other.

It’s an incredible honor to be present at this juncture of my young students’ lives, shepherding them along the trail toward whatever kind of writers they grow up to be.

*

Once I moved from writing about my experiences as a camper in poems and stories to working at a camp full-time, my artistic life began to change in earnest. Spending time with young writers whose only goal was to explore and develop their own creative voices—not just echoes of my voice—without the pressures of traditional education has helped to restore my natural impulses as a writer.

If I ever return to higher education, it will be as someone profoundly changed: working at a summer camp with young writers took me back to poetry’s roots and forced me to question the assumptions I held about the art form, gave me freer rein to teach what and how I wanted to teach, and removed me from the isolation of the ivory tower—all of which made me acutely aware of poetry’s role in the so-called “real world,” both what it is and what it can be. Working with students at this age, who are so new to creative writing that they practically glisten and quake like foals, forced me to reassert why the first creative sparks began to fly for me and think deeply about why I continue to write.

At summer camp, the day-to-day is poetry: students ask me to protect a clutch of eggs they saw a turtle lay in the sand. They trust me with their precious young selves when they ask how to navigate their desire to “publish” in our class anthology (which I produce by hand) under their chosen name when they’re not out at home. Once I found one of my students bushwhacking pensively through a patch of woods nearby during studio writing time—when I asked him to continue to work on the poem prompt I’d offered the class he said, quite seriously, “I am.” (And I believe him.)

If you’re reading this now, this is your sign to grab a stick and a pen and clear some trail for yourself this summer, or any day. It’s your sign to go outside.

__________________________________

Happy Everything by Caitlin Cowan is available from Cornerstone Press.

Caitlin Cowan

Caitlin Cowan is the author of Happy Everything (Cornerstone Press, 2024). She has taught writing at the University of North Texas, Texas Woman’s University, and Interlochen Center for the Arts. Caitlin works in arts nonprofit administration for Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp, where she serves as Director of International Programs and as Chair of Creative Writing. Caitlin also serves as Poetry Co-Editor at Pleiades and writes PopPoetry, a weekly poetry and pop culture newsletter. She lives on Michigan’s west coast with her husband, their young daughter, and two mischievous cats.