None of the Above: On Writing a Biracial Protagonist

Claire Stanford Considers the Answers to Questions of Racial Representation and Identification

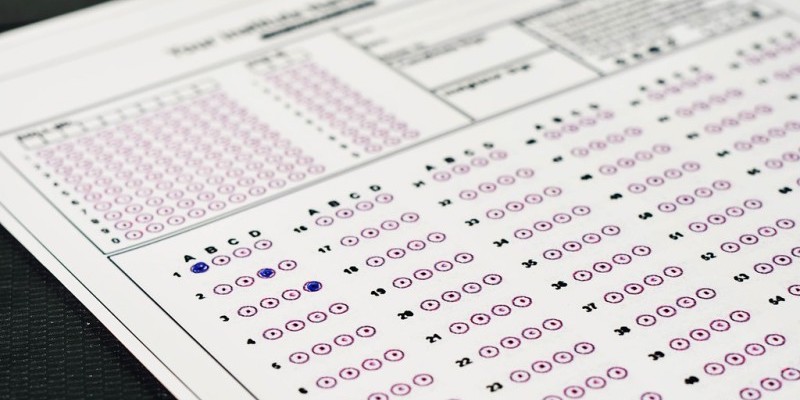

When I was a kid, I loved taking standardized tests. I liked carefully filling in the little bubbles with my number two pencil; I liked making sure my number two pencil was sharp; I liked, I think, the certainty that one of the four possibilities—A, B, C, or D—was always a correct answer, the illusion that, if only I read the question carefully enough, if I thought hard enough, I would always be able to be right.

I took these tests every year of elementary school. But there was one part of the test that caused my eight-year-old self, my nine-year-old self, my ten-year-old self ongoing consternation. When it came to reporting my race, on that very first page of the answer sheet, I never knew which bubble to fill. Asian? White? Other? My mother is Japanese American, and my father is white (and Jewish), and in the mid-1990s, you could only select one choice.

I can’t remember for sure, but I feel almost certain that, year after year, I chose Other.

*

I arrived in Minneapolis in the fall of 2009 to start my MFA program. I had applied with two short stories, both about white women. One was about a white woman who worked as an obituary writer in Alaska; the other was about a white woman on a babymoon in Hawaii. Nowhere in the stories did I specify that the women were white, but nowhere in the stories did I specify that they were not white, either. I pictured them both as white, and I’m fairly sure my readers did, too. Over the course of the three-year program, I wrote many, many more pages, almost all of which featured white women: a white woman scientist, a white woman divorcée in Maine, a white woman divorcée scientist in Montana. (I was neither a white woman nor a divorcée nor a scientist.) Some of these stories were successful, and some of these were not, but what they all had in common was that the protagonist was a white woman—not Jewish, just white—and that the story never explicitly said that the protagonist was white, but rather assumed that the reader would assume she was.

My second year, I started work on my first novel, that now lives in a long unopened file on my computer. This time, I focused on three protagonists: a Jewish woman, a Japanese American woman, and, still, a white woman who was just white, this time from Indiana.

A novel, of course, does not have to be autobiographical. But first novels often are. And yet, I had gone only so far with my autobiography, bifurcating myself into two characters, and throwing in my usual white woman who was just white for good measure.

*

What did it mean that I so studiously avoided writing a biracial protagonist?

1. I had never read anything with a biracial protagonist

2. I didn’t think anyone other than me would want to read anything with a biracial protagonist

3. I was waiting for someone to give me permission to write a biracial protagonist

4. All of the above

*

Several years after finishing my MFA, I started a new first novel. It was based, originally, on the short story about the white woman scientist, who was developing a wearable device that reads the user’s emotions. But after several false starts, I realized that writing from the point of view of the white woman scientist wasn’t working. I felt far away from her.

I moved onto a new protagonist, creating an assistant for the white woman scientist—another white woman.

It was only after several more false starts that the novel’s ultimate protagonist (and narrator) began to emerge: a half-Japanese, half-Jewish woman named Evelyn Kominsky Kumamoto.

I remember the first scene I wrote with Evelyn. I was sitting in my new living room in LA, in a white chair that I had taken from my parents’ attic in Berkeley, and I was writing—at a feverish speed unlike anything resembling my usual pace—about Evelyn meeting her best friend, Sharukh Teitelbaum (Sharky, for short), during their liberal arts college’s freshmen orientation. They are sitting in what Sharky later calls a liberal arts feelings circle, and, after they introduce themselves, Sharky approaches Evelyn immediately, asking her if she is a Jubu—a Jewish Buddhist, by which he actually means not a Jew who practices Buddhism, but a half-Asian Jew. Evelyn is shocked that Sharky can tell, shocked that he, too, is a half-Asian Jew. She is shocked to be seen, to be recognized.

*

A few years ago, I tried out an app that was making the social media rounds. The way the app worked was you took a photo of yourself—a selfie—and then the app would trawl its image archive of paintings to match you with similar portraits. I was intrigued. I saw my (white) friends posting beautiful images of the (white) women they matched with: Klimt’s “The Woman in Gold,” Vermeer’s “Girl With a Pearl Earring.”

I took my selfie. I waited as the app scanned my face, little white dots sparkling around the image of my cheeks, my eyes, my mouth. I watched as my results appeared.

My top match was a painting of a baby, “Portrait of a girl in white” by Carlos Baca-Flor. It was a cute baby, chubby-cheeked like me, with dark eyes and wild hair. It was funny, and it could have been much worse. In subsequent days, I would see other people of color posting paintings of indentured laborers, of geishas, stereotypes of every color of the rainbow except white, because that was all the algorithm could produce when given the task of matching a non-white face. (That was, perhaps, all the museums held.)

And yet, even though the picture of the baby was funny, it still hurt. I felt silly that I had let an app hurt my feelings—let an app disappoint me. What else did I expect? Of course there was no masterpiece that looked like me.

*

When the largest search engine in the world can’t find a single painting that looks like you (other than a portrait of a baby), the problem is:

1. That something is wrong with you

2. That art is too limited

3. That the search engine is too limited

4. Both B & C, but not A

*

I knew that nothing was wrong with me, and yet, I still didn’t post the painting of the baby. Instead what I did was put that scene—and that desire for recognition—into my novel. The people who asked me where I was from; the people who peered into my face, too polite to ask where I was from but not too polite to signal that they, nonetheless, wanted to know where I was from; the people who assumed I wasn’t Jewish; the people who, even when I explained I’d had my bat mitzvah, that I had gone to Hebrew school for eight years, still insisted that I couldn’t be Jewish; the people who wanted to know if I’d ever been to Japan; the people who wanted to make sure I knew that they had been to Japan; the people who referred to me as white and scoffed at me when I pointed out that I wasn’t, in fact, white.

*

Once, during my MFA program, my cohort and I were sitting at a long, sticky table at our usual Minneapolis dive bar. The CC Club, on the corner of Lyndale and 26th, three blocks from my apartment, complete with red vinyl booths and Big Buck Hunter and pitchers of Bell’s Two Hearted. Somehow, the fact that I was half-Japanese and half-Jewish came up. That’s so interesting, the classmate sitting next to me, a white man who was serious and thoughtful, said. You should write about that.

He was right, but mostly what I felt when he said it was not recognition, but rather a spotlight, shining on all the ways I didn’t fit in, had never fit, would never fit. I had been trying for much of my life to be less interesting, less striking, as I was often called, rather than being called pretty.

The memory of that night at the CC Club came back to me years later, after my actual first novel—my first published novel—had sold. I had dismissed the advice out of hand, and then completely forgotten about it. I still wonder if I would have taken the advice if it had come differently, in a different moment, from a different person, with a different set of words. I wonder about the years I lost to writing these unraced white women.

Why, I wondered, hadn’t I realized that I could write about a half-Japanese, half-Jewish protagonist then? Why had it taken me so long to figure it out for myself?

*

What are you, what are you, what are you; where are you from; where are you really from? This had been the refrain of my childhood and adolescence, even in the progressive Bay Area.

What I learned—what I was taught by this refrain—was that I was illegible.

*

In her 1986 essay, “The Carrier Bag of Fiction,” Ursula K. LeGuin writes that she struggled to see herself in the typical “tale of the Hero”—a story shaped like Freytag’s Triangle, shaped like a spear, shaped like violence, shaped like, particularly, male violence. These stories shape how we think of the human, of who gets to be considered human, of who is legible in our society. “Wanting to be human too,” she writes, “I sought for evidence that I was.”

When I was growing up, being biracial meant I was an oddity. An outlier. Not Asian American, not Jewish. Nothing. I learned not to expect to see myself in the stories I read, in the movies I watched, in the world around me. Wanting to be human, too, I sought not for evidence that I was, but for ways to fit myself into other stories, to conceal myself behind an unraced narrative that would be more palatable, more universal. I didn’t do this consciously, of course, but with that insidious unconscious drive to fit in, to change my shape.

I wish I could write here about a time I brought a story to workshop, a story of a half-Asian, half-Jewish protagonist. I wish I could write that it was received badly, about the stereotyping comments my workshop made, the thoughtless remarks. Because that would mean I had been brave enough, aware enough, to even try to write that story.

*

How did I decide to make myself legible? I wish I had a straightforward answer. In fact, a number of things changed. I got older. The world moved forward, ever so slightly. I found a new mentor, who encouraged me to dig into what was urgent in my work. The unraced white women were not urgent, not to me. My new mentor was a Black man who wrote about being a Black man; finally, I was, in a sense, given permission.

And I gave myself permission, trickier than it sounds. My first attempt at a novel—the one I wrote during my MFA—had failed to make it out into the world. I had workshopped it and revised it and workshopped it and revised it and re-typed it and refined it until I no longer recognized it as something I wanted to say. I decided, if I was going to write another novel, this one on my own time, that I was going to write what I wanted to say. I was going to try to excavate something from deep inside myself, even if I was the only person who wanted to read whatever dark and tender thing I found there.

This excavation is, of course, easier said than done.

It is always difficult to excavate something from yourself, to put it on the page, to subject it to public scrutiny. But how much more difficult does that excavation become when the material you are digging up is something you have never seen before? That you’ve been told—implicitly or explicitly—is not legible, not worthy of art?

What I learned was to write what I wanted to write anyway.I’d like to say I learned to quiet the voice that told me what I was writing was unworthy, but that’s not exactly true. What I learned was to hear the voice and to make my own stronger. What I learned was to write what I wanted to write anyway.

*

Even now, as I write this essay, I can feel the worry itching at the back of my mind, that instinctual fear that no one will be able to relate to my experience. Relate, that loaded word.

*

When people (fellow workshoppers, professors, agents, editors, readers) say they can’t relate to your writing, that means:

1. That something is wrong with you

2. That something is wrong with your writing

3. That you are not human

4. None of the above

*

As I was in the process of writing this essay, I needed to find a new doctor. I had moved to a new city to start a new job, and so I needed a new health care provider. Two days before my new patient appointment, I got an email, asking me to fill out my forms online. When I got to the usual question of race, the options on the scrolling menu were more detailed than I was accustomed to, listing out each race that, I assume, had unique health indicators: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian Indian, Black or African American, Chinese, Filipino, Guamanian or Chamorro, Japanese, Korean, Native Hawaiian, Other, Other Asian, Other Pacific Islander, Patient Refused, Samoan, Unable to Obtain, Vietnamese, White. The directions said to press the Control key to select multiple options. I clicked Japanese; I pressed the Control key; I scrolled down to white; I clicked white. But instead of selecting Japanese and white, it highlighted Japanese and white and every race in between. I tried doing it again, I tried clicking on the options in a different order, I tried the Shift key instead of the Control key, the Option key instead of the Control key, but every time I got the same result.

In my novel, the biracial narrator, Evelyn, similarly wrestles with a drop-down menu that refuses to allow her to be both Asian American and white. I thought about this as I wrestled with the health care center’s drop-down menu. When I had seen that you could press Control to select multiple options, I had been relieved; I had thought it was a sign of progress. And I suppose it was, but progress was still glitchy.

*

I think of the nine-year-old version of myself, sitting at her desk in her fourth-grade classroom, holding a sharp pencil, staring at those bubbles that have no place for her. I wish I could tell her that she has done nothing wrong, that there is nothing wrong with her. I wish I could tell her that it is not her fault that she is trapped in categories that someone else has made, categories so limited in imagination that they force a child to fill in the bubble next to Other, meticulously shading it with the pencil lead, careful not to go outside the lines. I wish I could tell her that she will find a way to make herself legible, word by word, writing outside of multiple choice, outside of standardization.

*

At my appointment, I tell the doctor that there is a problem with the form, and then I lean forward so she can put a stethoscope on my back, to listen to my breath, to my heart.