Nihilism or Wonder? On the Evolution of the Alien Story

Investigating Extraterrestrial Metaphors for Communism, Religion, Love & Art

Calvin, the Martian creature at the center of Daniel Espinosa’s new sci-fi horror film, Life, lives happily enough on the International Space Station, doted upon by six loving astronauts. An unpromising thing in a petri dish, Calvin is the astronauts’ first living sample from Mars—a science project which the astronauts tend to like a weird pet. When he grows tentacles, they coo at him parentally. And when he starts eating body parts, they react with a stoic good humor. Instead of screaming, they push buttons on control panels and confer about protocol. Sometimes, they even pause to remind themselves explicitly of the movie’s guiding philosophy: that aliens, at the end of the day, are just like us. “He doesn’t hate us,” one astronaut observes, minutes before Calvin mauls him to death. “He’s just trying to survive.”

At times, Life seems to argue that all intelligent life is as brutally generic as Life itself: bloody, exploitative, bound by violent conventions. It’s a clever reworking of the cliche that life imitates art—though Life, in this case, imitates the movie Alien. Like Ridley Scott’s 1979 horror classic, Life is a tense thriller about an evil alien in a small space. But where the movie frustrates isn’t with its unoriginal premise; rather, its with the pedantic insistence that there’s nothing original left in the universe. Calvin might be a flesh-eating space monster, but everyone in Espinosa’s film insists that his predatory violence signifies just more of the same. All of life, remarks one character “demands destruction,” on Earth and, apparently, in outer space. It’s an outlook cribbed from Nietzsche and marathons of Animal Planet, and it contends that all we can know of other life forms are the brutal facts we know of ours.

“Life seems to argue that all intelligent life is as brutally generic as Life itself: bloody, exploitative, bound by violent conventions.”

Life, then, is an alien movie that refuses the possibility that there might be anything truly alien at all. In a different film—and, in fact, in some recent ones—that idea would be leveraged in favor of some New Agey cosmic optimism, an E.T.ish insistence that all of life is transcendentally connected. While that kind of optimism might seem unsustainable in these pessimistic times, it allows for the possibilities of wonder and novelty that Life’s nihilistic posturing does not. And ultimately, we look to the movies for the same reason we look to outer space: in the hopes of seeing something that we haven’t seen before, and of maybe being moved by what we find there.

One of the strangest things about Life is how aggressively it resists the anodyne storytelling of sci-fi blockbusters from the past few years. Interstellar and Gravity both used space to stage bathetic stories of love and resilience, as did The Martian, which turned the red planet into a frontier epic of human resourcefulness. Even last year’s Arrival meditates on utopian ideas, albeit with uncommon grace, imagining the ways that non-human intelligence might guard us from the brutalities of our own. Those movies, with the significant exception of Arrival, feel like happier siblings to Espinosa’s Life, except they use cosmic unknowns to articulate familiar platitudes rather than adolescent nihilism. Their reference point isn’t Ridley Scott’s Alien, but the friendly sci-fi classics of the late 70s and early 80s, like Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, or more obliquely, even the Star Wars and Star Trek franchises, which more often imagine aliens as plucky sidekicks than hostile invaders from other planets.

That decade’s starry-eyed optimism about outer space drew on a lot of cultural forces, including, undoubtedly, the optimism of the Space Age itself. But it also intersected with new ways of thinking about intelligent life in the universe—some of them genuinely new, and some of them goofily New Age. In the early years of the Cold War, aliens in popular fictions were generally metaphors for an assortment of geopolitical terrors, namely nuclear war and communism: what Susan Sontag referred to in an early essay on science fiction as “The Imagination of Disaster.” But by the early 60s, aliens and the apocalypse—nuclear or otherwise—had become linked to an astronomical theory with surprisingly utopian implications.

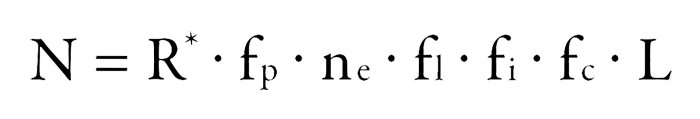

In his 1985 book The Varieties of Scientific Experience, the beloved science popularizer Carl Sagan discusses something called the Drake equation, named after astronomer Frank Drake and “used to predict the number of civilizations in the Galaxy with the technology to permit interstellar contact.”

According to the equation, the number of advanced civilizations in the universe depends on a range of cosmic uncertainties, from R, the rate of star formation, to L, the “average lifetime of the technical civilization.” It’s that last variable, as Sagan writes, “that’s by far the most uncertain,” and which “binds up this quite outre subject of extraterrestrial intelligence with the most pressing human concerns”—namely, nuclear war. The value of L must reflect our own prediction of how long we’ll survive: we’re the only advanced technical civilization of which we have any knowledge. That’s why, as Sagan writes, alien contact would be such good news: it’s proof that another civilization has survived the threat of self-annihilation long enough to reach us through space and time. It means that having incredibly advanced technology—like the kind that permits interstellar contact, but also like the kind that permits nuclear war—isn’t a death sentence.

“That’s why, as Sagan writes, alien contact would be such good news: it’s proof that another civilization has survived the threat of self-annihilation long enough to reach us through space and time.”

Far from portending the apocalypse, the Drake equation suggests that alien contact bodes well for our own chances of survival and that our fate is bound up with the fate of life elsewhere in the universe. That belief imbues some of the more eccentric theories of the human-alien encounter, like those of Dr. Jill Tarter, the former director of the Center for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) who believes that, if aliens ever contact us, it’s either evidence that they have no religion or, as the scholar David Wilkinson writes, “that their belief in God [is] so far in advance of our form of religion that we will convert to it.” But, beyond the walls of SETI, the Drake Hypothesis also has echoes in New Age junk science.

By the 70s, UFO narratives had been “adopted simultaneously by resurgent post-watergate conspiracism,” writes David G. Robertson in his book, UFOS, Conspiracy Theories and the New Age, and also as symbols of “cosmic intelligence, which played a significant role in the development of the New Age” spirituality and holistic thinking. Twenty years later, the two merged into what the scholars David Vaos and Charlotte Ward describe as “conspirituality,” or the hybridization of the “world-affirming, cultic New Age and the world-rejecting conspiracy milieu.” One of the popular examples of that hybrid thinking—and one especially agitating to Carl Sagan—is the so-called ancient astronaut theories, largely popularized in the book Chariots of the Gods by Erich von Daniken, which holds that human civilization began when alien travelers alighted on Earth sometime in prehistory, built a couple pyramids, and then returned to space forever.

Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival is, in its own way, an ancient astronaut story: a near-future in which an advanced intelligence gifts the tools of civilization—in this case, a clairvoyant written language—to a less advanced one. But Arrival transforms von Daniken’s thesis from 70s junk-science into what Jia Tolentino, at the New Yorker, describes as a “humble and brave ontological position.” Arrival, like the Spielberg films before it, suggests that all forms of life are bound by a common lot, even by a common goodness. By the film’s conclusion, audiences still know little of Abbot and Costello, the two alien “heptapods” who communicate with Louise, the linguist played by Amy Adams, when their space ship touches down in Montana. But we know that the question of their survival is bound up with ours: they teach Louise their language as a favor that they hope humankind can repay 3,000 years in the future.

What’s so lovely about Arrival, unlike Life, is that its theory of life, however general, isn’t meant to foreclose wonder about the universe. It doesn’t cut down cosmic mysteries with a nihilistic pose of knowingness, or assume that there’s nothing new to be discovered in the galaxy. The dominant images in Arrival are ones of mystification: of Amy Adam’s awestruck face; of unfathomable spaceships hovering in mid air; of a hieroglyphic language of urgent, imperfect meanings. That uncertainty is also central to that film’s understanding of life—not as a brutal calculation of self-interest but as an incalculable balance of joy and grief.

“Residing somewhere on the far side of certainty, wonder is as much an ethical position as an intellectual one. It cops to not knowing, and to the possibility that some things might not be knowable at all.”

Alien stories remain so generative because they’re uniquely capacious allegories for the things that command belief: communism, religion, mysticism, love, and art itself. Arrival uses aliens as metaphors for the joint processes of meaning-making and moviemaking, as Jordan Brower writes for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Close Encounters of the Third Kind renders the alien encounter as a literal melody, a five-tone sequence exchanged between a military base and a visiting spaceship. Even the central image of E.T.—of human and alien fingers touching—evokes one of the most famous images in Western art, Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. In his final book, the famous psychoanalyst Carl Jung described UFOs as “technological angels,” emissaries not from outer space but from the human id. Even if you don’t subscribe to the notion of an unconscious, suffice it to say that both aliens and art share their status as imaginative creations: at least for now, aliens are some of the most compelling works of fiction that we have.

And that’s why Life’s dismal assessment of aliens and outer space feels also like a dismissal of storytelling itself. Good space movies understand that both art and aliens should prompt an experience of wonder—or that “the preservation of simple human truths requires mystery,” as the scientist Kris Kelvin observes at the end of Andrei Tarkovsky’s science-fiction masterpiece, Solaris. Residing somewhere on the far side of certainty, wonder is as much an ethical position as an intellectual one. It cops to not knowing, and to the possibility that some things might not be knowable at all—not as a New Agey celebration of mystification for its own sake, but in a frank admission that minds, like people, have limits.

That admission is where Life fails, and why Arrival is so adept at articulating a delicate kind of hopefulness. It’s a story of uncertainty, which, as Rebecca Solnit writes, is the condition out of which hope arises. Art can no more forestall a nuclear apocalypse than aliens can, but the best stories can still help us prolong the present, letting us linger in unworldliness and ambiguity a little longer. They remind us that we’re still capable of greeting the the extraordinary, and, if we’re lucky, of encountering something good.