At its peak my obsession with her was like a form of self-harm: a private source of pain and comfort.

When I found the ring box in the back of the drawer, I didn’t want to open it. Navy and heart-shaped, it has a finely brocaded border and thin silver hook. The lining is pearly satin indented to hold a delicate jewel. A market seller provided it for a sard ring I’d bought, shoving the chunky band

determinedly into the slot. I could’ve saved him the trouble; I’d no need for the box, yet was captivated by its fairy-tale charm. On leaving the stall, I slid the ring onto my finger and smoothed the satin back into a tight clasp.

For almost two decades, I haven’t looked at what’s inside the box. Simply having it in the room will hopefully pull me through my task. When doubts hover close, I move it about restlessly. I place it behind my computer as if its reliquary power can channel through the screen, or hide it far away on

the windowsill by the moldy coffee cups. Getting up from my desk, I pace the room with it in my palm.

Since being unable to sleep, I’ve passed through a shadow curtain. The present has become dark and stagnant; the past circles vividly around me. Sharp memories cut through chronology’s thin skin. In the strange energy of these insomniac nights, I have begun to write as consolation. To make a story that will put an end to reliving flash fragments, to remembering only the most troubling details.

Easily, I slip back to the day I first saw her. I had a job in media monitoring; we provided clients in cars and construction with daily updates of press content. The articles were selected by senior analysts; my work was to write the summaries. Given that copying out the opening paragraphs brought no complaints, I wasn’t motivated to do much more.

Excused from staff meetings due to client deadlines, I’d twirl about in my office chair. Shutting my eyes, I’d picture the second floor, open plan and strip-lit. The boards separating cubicles decorated with photographs of loved ones, families, and pets. One neighbor’s neat lineup of sharpened pencils, another’s orderly stack of camomile and fennel teas. My desk strewn with tire-related articles, my board pinned with ideas for me and Graham, my boyfriend. The drawn conference room blinds meant I didn’t need to picture my conventionally dressed colleagues. Who were, in turn, spared the sight of me: a woman in a faded sweater and jeans with a mid-length tangle of orange hair.

No matter how often I played the game, when I looked again my surroundings would be both as I’d visualized them and not. The concrete materiality of the objects was identical but the colors, the quality of light, the atmosphere were subtly different. See, I’d tell myself, you don’t know it all. Things change. You can’t predict how they’ll seem in thirty seconds, never mind till the end of time.

One August morning with sixteen months to the end of the twentieth century, I was more wrong than usual. When I blinked back into the room, a new person was seated opposite me. She didn’t appear to have noticed my twirling around in Megan Groenewald’s world—but while I’d have noticed her anywhere, in east London suburbia she was like an exotic zebra fish that had swum off course.

She wore a short, black-and-white, Bridget Riley–type number. Her build was lean, long-limbed, and coltish; her hair was a shallow sea of inky curls. She had fine, straight features and close-set blue eyes so dark as to glint like pitch. I wanted to introduce myself but the cords that looped from her ears to her Walkman put me off.

Since she was typing like a demon on her keyboard, I flamboyantly increased my own speed. When my document contained more errors than words, I glanced at her. She lifted her head; she had a slight squint.

“I’m Meggie,” I said.

“I’m Sabine.”

“What are you listening to?”

She took her earphones out. Her hands trembled as she passed them over to me; her nails were bitten to such small tabs that her fingers seemed entirely made of skin.

Surprised she didn’t mind me sticking her earphones in my ears, I listened. An expressive male voice sang tenderly to a sweeping accompaniment. Wiping the earphones off with my thumbs before handing them back, I said, “I like it.”

“It’s ‘La Chanson des vieux amants’ by Jacques Brel.”

“Are you French?”

“Belgian. Jacques Brel is Belgian.”

“No,” I said. “Are you French?”

“Belgian,” she said, “but yes.”

Then she added, “Also German, Jamaican, Jewish, Egyptian. It’s a long story—”

“You don’t have to go into it.”

“Thank fuck. I hate this question.”

“People ask me all the time too.”

She frowned. “If you’re French?”

“No, where I’m from. When I say, South Africa, they say, Don’t you miss the weather? I wish I could press a button to answer them.”

She cocked her head to the side, biting her lip. “You are how old?”

“Twenty-three.”

“Me too.”

We looked at each other.

“I don’t know much about Belgium,” I said.

She shrugged. “It’s flat. How about South Africa?”

“Parts are flat, parts are mountainous. Growing up there in the eighties . . .” I hesitated; she waited. “I knew things were wrong. I felt it as a child. But I didn’t fully understand. Now I do but I’m here.”

What was I getting at? Speaking about this could be awkward. The music from the earphones in Sabine’s hand had changed to a tune with a strong beat.

“It’s complicated,” she said.

I nodded. Ten minutes later, an apple jelly bean clipped my shoulder. When I looked up Sabine had popped her earphones back in. Her English was almost perfect; the tone of her voice was mesmeric and low. I sucked the tart sweet slowly.

For the rest of the day, I imagined conversations in which I said the things I wished I had and asked the things I wanted to know.

__________________________________

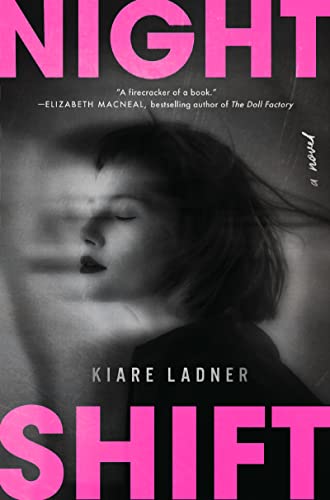

Excerpted from the book Nightshift by Kiare Ladner. Copyright © 2021 by Kiare Ladner. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.