And in the cemetery, she has become lost.

A day in early winter slipping to dusk. Impulsively she has decided that it is imperative to visit Whitey’s grave.

Desperate to be there. The first time, when the ashes in the urn were buried, she’d been too distracted to fully comprehend.

Whitey had not instructed them to scatter his ashes in some romantic place like a river, a lake, a canyon. Hadn’t wished to think that far into the future, also wasn’t the type to take himself so seriously.

Self-importance embarrassed him. Worst thing Whitey could say of someone—He’s full of himself. Christ!

Cremation he’d wanted. Not a formal burial. But he had not elaborated. Enough, let’s get it over with.

And here is the problem: the (temporary) marker provided by the crematorium is so small and so resembles other small utilitarian markers in the cemetery, the widow becomes confused in the waning light, and loses her way. She and the children have ordered a beautiful granite grave-stone of respectful proportions that will bear the stately carved words

BELOVED HUSBAND AND FATHER

JOHN EARLE MCCLAREN

but this stone is still at the stonemason’s. In the meantime the widow seems to have mis-remembered the (temporary) marker as larger than it is, easily two or three times larger, and so keeps missing it. Her feet in impractical shoes sink in the spongy earth. Her nostrils pinch with a sharp smell of sodden-leaf rot and the futility of such acts of desperation. For always the widow is seeking something that is lost, that is not-here.

Trying not to panic. Oh, how can she be lost!

It is not like Jessalyn McClaren, who has always been the person who knows the route, took time to write down the address, has an idea where to park, knows precisely when. Certainly she knows that the grave marker is nearby. She is certain.

Descending a muddy hill. Rain-flattened grasses, slick mud of the hue of offal, and as badly smelling.

Trying to cross a patch of muddy grass, a shortcut to a graveled walk-way. Her ankle turns, she falls suddenly, heavily.

In the cold muck, sobbing.

Whitey! Please let me come to you, I am so tired.

A fellow visitor to the cemetery, on his way out, sights her. Possibly (she will think afterward) the man had deliberated whether to acknowledge her, a drunken-seeming woman, a confused woman, a heartbrokenly sobbing woman who has slipped in mud, has fallen in mud, graceless.

But he doesn’t disappear. Gallantly he comes to her, and helps her to her feet. This touch—this sudden physical contact—from a stranger—is overwhelming to Jessalyn, like an unexpected eclipse of the sun.

A relief, he seems to be no one who knows her. No one whom she should know.

“Here. Try these. . . ”

The gallant stranger provides tissues for Jessalyn with which she can wipe at her muddied clothes. Standing at a polite distance he does not assist her.

Through tear-dimmed eyes she sees: he is a man not-young, not-Caucasian, with a swarthy creased face and kindly eyes, a drooping Brillo pad of a mustache. He wears a tweed jacket with leather patches at the elbows and on his head a dandyish hat like a Stetson. He is tall, angular, wary and alert as if he fears that Jessalyn will collapse again into the mud, and he will be obliged to haul her out.

He asks if she is all right? His manner is oddly formal, wary—he calls her ma’am.

Jessalyn wonders: Is he afraid that the white lady will panic and begin screaming?—is he afraid of her?

Embarrassed, she assures the gentlemanly mustached man that she is not injured—she is just a little muddy. “But, I guess—I’m lost. . . ”

“Lost?”

“I mean—I can’t find the g-grave that I am looking for.”

She tries to laugh, this is such a ridiculous predicament.

With something like pity the man regards Jessalyn. A woman wandering lost in this small cemetery, which can’t cover more than two or three acres?

Jessalyn wonders: Is he afraid that the white lady will panic and begin screaming?—is he afraid of her?Politely he asks which grave she is looking for and she tells him— “The grave of ‘John Earle McClaren.’”

There, it has been said: THE GRAVE OF JOHN EARLE MCCLAREN.

The mustached man does not seem to register how profound this utterance is for Jessalyn. He does not seem to register that the muddied woman standing before him may well be the widow of the deceased who has become lost searching for his grave.

Nor does he seem to register that McClaren is a name of some local significance. No?

“Well. Let’s see what we can do for you, dear.”

Dear. The widow feels the jolt of this casual word like a caress that is unexpected, though (perhaps) not unwanted.

Dear. As a kicked dog would feel when it is stroked, and not further kicked.

The mustached man is carrying something like a pack, out of which he takes a flashlight. One of those pencil-thin flashlights with surprisingly strong beams.

“What does it look like? The grave stone.”

“Oh, it doesn’t look like anything, really,” Jessalyn says apologetically, “it’s just one of those little, temporary markers that are all over the cemetery. You know, the funeral homes provide them, or—the crematoriums.” Pausing, stricken. Of course, Jessalyn knows to say crematoria except the word seems pretentious uttered in this place, to the mustached man in the Stetson hat.

Is he touched by her air of apology, her distractedness, so thinly masking the most profound despair? Is he amused by her muddied clothes, expensive tasteful clothes, a black cashmere coat, impractical leather shoes?

Of course, he must have guessed that Jessalyn is the widow. Widow has become her essence.

Shining his narrow laser-beam of light along the lumpy ground he leads Jessalyn past rows of grave stones and grave markers. Some of the grave markers are very old—faint, carved dates as long ago as the 1880s. Some are covered in a scabrous-looking moss. Jessalyn is trying to keep up, following close behind the mustached man. She sees that he is taller than she by several inches—taller than Whitey. Beneath the Stetson hat cocked at a rakish angle his hair is a tangle of gray and silver, as long as Virgil’s hair. She wonders if he knows Virgil: if he and Virgil know each other. (But he had not seemed to know the name McClaren. Though she is the least vain of persons Jessalyn is mildly hurt by this.)

“Sorry, dear—am I going too fast?”

“N-No. I’m fine.”

Dear. No one has called her dear since Whitey.

Not drunk but why is she stumbling, can’t seem to keep her balance on this uneven ground, the harsh fresh wet air is making her light-headed. Since the ordeal of the vigil and the passing-away and its aftermath she has lost her sense of what it requires to be upright—how to walk without swaying and stumbling.

A neurological problem, perhaps. Deficit—that dread word.

How quickly it can happen: stroke, deficit. Each morning the widow wakes astonished and guilt-stricken that it has not (yet) happened to her. The mustached man offers Jessalyn his arm but she pretends not to notice. She is stricken with shyness, doesn’t want to come too near to him.

“Ma’am? Over here?—did you look here?”

Darting like a snake the laser light moves along the ground. Jessalyn’s eyes follow with a kind of dread.

“There—that’s it. . . ”

How small the grave marker from the funeral home is, how meager, a dull pewter-color—JOHN EARLE MCCLAREN 1943–2010.

Is this—this—all there is, she has been seeking so desperately? As if her life depends upon it?

She feels a moment’s vertigo. How small it’s all.

“You’ll be all right now, ma’am? Don’t stay long, it will be dark soon.” The mustached man speaks in a kindly voice, with a faint, very faint accent. Is he—Hispanic? Middle Eastern? Jessalyn has not failed to notice how he glances about as if seeking someone else, a companion of Jessalyn’s perhaps, who will be responsible for her. She has the impression—oh, she is embarrassed!—that he is eager to escape her.

“Thank you. You’ve been very kind. But I’m fine now—I won’t get lost again.”

What a foolish thing to say!—won’t get lost again.

Jessalyn tries to laugh but the sound comes out unconvincingly.

No matter, the tall kindly mustached man has turned away, walks away.

At the gravesite, churned earth. Some sort of earth-digging machine must be used in the cemetery though (possibly) Whitey’s grave is shallow, containing only an urn: a strong-armed gravedigger wouldn’t have much trouble using just a shovel.

Here is something jarring: Whitey’s grave abuts another grave with very little space between.

How did this happen? Did someone miscalculate? Whitey’s near-neighbor has a large square-cut slab of ugly stone carved with the name Hiram J. Horseman—about which Whitey would surely make a sardonic remark.

Actually it is Housman not Horseman. Look again, darling.

Jessalyn looks more closely: the name is Housman. Hiram Housman.

Neighbors in the cemetery though strangers in life. So far as Jessalyn knows.

“Oh, Whitey! It is all so—futile. Isn’t it!”

Silly to have come here when Whitey, her Whitey, is likely to be back in the house if he is anywhere. He is not here.

The harsh wet open place inhabited by strangers—grave stones of strangers—is not a friendly place for Whitey, or for her.

Yet Jessalyn lingers at the grave. Nowhere to sit here, nowhere to rest or lean against for she cannot lean against, still sit on, the grave-stone of Hiram Housman—that would be disrespectful.

She’d meant to bring flowers. Oh, she’d left flowers in the car . . .

Her heart thuds with disappointment. A widow is one who forgets, who leaves the flowers in the car.

(Oh God—where are her keys? In her handbag? Blindly, frantically she rummages for her keys amid wads of tissue.)

(Why does she never remember to empty her handbag of used tissues? It is a fact, she cannot remember to do this.)

Now it is becoming dark. Seriously dark. Jessalyn rouses herself to leave the cemetery.

Here is one good thing: it is far easier to make one’s way out of a cemetery than to make one’s way in. Small pathways lead to a single wide graveled walkway at the center of the cemetery, which leads to the parking lot behind the church.

Exiting the cemetery the widow halts, and thinks; begins walking again, and again halts—for what did she lose? What has she left behind?

Searching through her handbag, and through the pockets of her coat . . .

Near the entrance gate the mustached man in the Stetson hat seems to be waiting. She is embarrassed to see him, she’d thought that he had vanished. He is being helpful—gentlemanly—aiming his beacon of light onto the graveled path, as Jessalyn approaches. Oh, she wishes he’d left her alone!

Feeling just slightly fearful as she approaches him. Telling herself it is not because he is Hispanic, or—Mediterranean?—it is not because of this. But she is alone, and the mustached man though kindly-seeming is a stranger. She has no other way to exit the cemetery unless she wants to abruptly retreat (which she certainly can’t do, he is watching her) and walk a considerable distance back toward Whitey’s grave, and even then, in the gathering darkness—oh God, she would never find her way out.

Why is this man waiting for her? Has he been lingering? Is there no one else in the entire cemetery—no one? Jessalyn feels her heart begin to pound in apprehension.

She has already thanked the man but nervously thanks him again— tells him again that he is very kind. But as she hurries past him to her car he addresses her—“Ma’am?”—and her heart leaps in fear of him.

“What—what do you want?”

“Your glove, dear. Is this your glove? Found it on the path.”

It is her glove. Soft black leather, muddied. With abashed thanks she takes it from him.

Driving home she hears the soft, caressing word—dear. Not a word she can trust, she thinks. Not ever again.

__________________________________

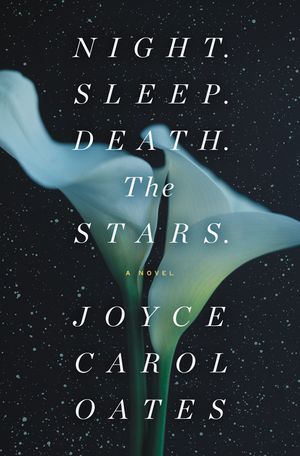

From Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. by Joyce Carol Oates. Copyright © 2020 by The Ontario Review, Inc. Reprinted courtesy of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.