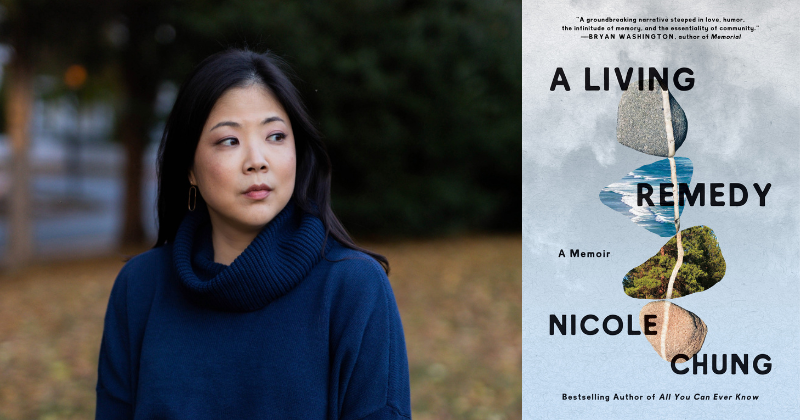

Nicole Chung on Writing Through Grief and How to Begin Again

Hannah Bae Talks to the Author of A Living Remedy

Reading Nicole Chung’s second memoir, A Living Remedy, feels like having an honest conversation with a wise, trusted friend about how to keep living through grief. In this book, Chung, a Korean-American writer who was adopted by white parents, writes movingly of losing both her father and mother to illness within the span of a few, short years while interrogating issues of class and the inequities of medical care in the United States.

In 2018, months before publication of Chung’s best-selling debut memoir, All You Can Ever Know, her father dies at 67 from diabetes and kidney disease, no doubt exacerbated by his lack of health insurance and limited access to care in the small Oregon town where she grew up. Less than a year later, Chung’s mother receives a terminal diagnosis for cancer that’s returned after years of remission. She dies in 2020, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, before it is safe for the author to visit in person and say goodbye.

“My parents passed so close together, and yet the amount of help I was able to give them when they were sick was like night and day,” she tells Literary Hub. “There was a lot more I could do for my mother as she was dying because I had gotten my first royalty check from my book and I was finally making a good wage in publishing, but that was not the case just a couple years earlier when my father died.”

Although the injustices that Chung describes in A Living Remedy are rage-inducing, she imbues her prose with a deep vein of generosity, guiding her reader with care through her painful losses. As a former student of Chung’s who also benefited from her editorial eye at Catapult magazine (RIP), I wasn’t surprised to find so much of her characteristic heart on the page. It was a comfort for me to reconnect with her to discuss A Living Remedy.

*

Hannah Bae: I keep telling people that this book is going to help so many readers. I know you were working on A Living Remedy for four years, and you sold it before the pandemic, when your mother was still living. I’m shocked at how timely it feels after we’ve all experienced such collective and individual losses. How has the book evolved over time?

Nicole Chung: I sold the book in 2019 between my hardcover and paperback tours for All You Can Ever Know. I was still processing my father’s loss, and I knew I wanted to write about how he died—the structural failings and the way he wasn’t able to access the care he needed for many years. That was part of the story from the beginning.

I felt compelled to write about grief but also this common American experience, where so many people in this country who are not fantastically wealthy end up facing illness or loss without all the resources and support that we need. I was left with so much self-recrimination after my father died, feeling like I or my mother and I should have done more. Ultimately, one of the great lies of these systems is that we blame ourselves or blame each other when they fail us. I used to blame myself for not being an expert at navigating this fundamentally broken system or not being able to guide my parents through it in a better way. I know it was not my fault. That was something I wanted to confront in my story, because it was an enormous part of my grief.

When my father died, the whole community rallied around my mother. During the pandemic, I couldn’t be with my mother, but she had such a good network of friends.

At the time, my mother was in remission [from an earlier diagnosis of breast cancer], and we had no reason to believe that she wouldn’t be fine going forward. It was only several months later, after she was diagnosed with terminal cancer, that I knew this book would change a lot.

I started over from the start, beginning in the fall of 2020, about five to six months after my mom died. My mother’s illness, the pandemic and her death really shifted the whole landscape of what the book was going to be. When I started over, I knew my relationship with her would be the emotional center of the book. That would give the book its narrative arc. I rewrote it with that frame in mind.

HB: I’ve been following your work online for years now, and I remember you mentioned in a social media post some time ago that you stretched a lot as a writer while writing this book. How did you feel yourself growing?

NC: A lot of it was through grief and what we’ve all been living through in the pandemic. I changed a lot, but also the entire world changed. There’s a real hunger and a real need for many people to remember what it was like to lose a loved one sight unseen or attend funerals on Zoom. Even though this isn’t a pandemic book—it’s only in a couple chapters—I hope that those sections, as hard as they were to write, can help people feel less alone. There hasn’t been enough space made or enough respect for what people have lost.

My relationship to writing had to shift in order for me to work on this book. Honestly, there were points where I took long breaks, like the months after my mother passed away. It was a long time before I felt like I had the emotional energy for long stretches of writing. In that time, I was journaling and jotting down notes of things I thought should go in the book, but I wasn’t actively working on it. That was really scary for me because I had this book contract.

I wanted to get back to the book, but I also knew I wasn’t ready yet. Being able to recognize that was a big change for me as a writer. Up until then, I was always a “push-through-it and get-it-done” type of writer and worker. I write in the book that I had a tendency to treat myself like a machine. Not only would that not have been good for me while writing, but it wouldn’t have resulted in this book.

I had to give myself grace. I had to be willing to approach my work from a place of trust, not fear. My prose in this book is a lot freer than it has ever been. I tried to be as present and fully myself in the writing. I brought my whole entire self to this book in a way that I’d never experienced before.

HB: The writing reveals such an exercise in contrasts. You capture your parents at different phases of life, when they’re vibrant and lively people and also when they’re at their most feeble. What was that memory work like?

NC: I cried while writing this book. I’ve never done that with a piece of writing before. It wasn’t my words that were moving me—I hope the words are moving, but that wasn’t what I was reacting to. For me, it was the mingled pain and joy of having to summon my parents, make them real on the page. It was demanding and sometimes joyful, and often it was really wrenching.

But it was important to me to show them at different stages, when I was growing up, in their better years and then the harder ones. One of my deepest fears was that they would come across as pitiable or emblematic of tragedy in some way, when they were so much more than that. I wanted to show them as close to their full humanity as I could.

HB: I don’t read a lot of nonfiction that examines the downsides of “upward mobility,” like who gets “left behind” or whom an upwardly mobile person is “unable to save” on their rise, even though these are feelings I’ve experienced personally. How did you approach writing about class?

NC: My parents didn’t have college degrees, and they were convinced that if I got one, that would be my ticket. I believed so strongly that if I were lucky enough to actually get into college and get a full ride, which is what I needed in order to go, that somehow I would work hard, pay my dues, bide my time and that I would be able to support myself and take care of my parents. That was really one of my goals.

I had to give myself grace. I had to be willing to approach my work from a place of trust, not fear.

What I wish I’d realized was that we didn’t have the time. I thought that by the time my parents really needed me to support them, when they’d need significant medical care, that I would be in a position to help. I just wasn’t quite there yet when my father was dying. That’s something I’m always going to have to live with, the attendant regret. I know rationally that I did the best I could and they didn’t blame me or expect more from me. But I’ll always wonder if I’d made different choices [instead of studying English and history in college] if I could have saved my parents from these diseases. That’s something I’m going to live with.

Growing up, I didn’t know the specifics of our financial situation. That’s partly why I shied away from writing about it for so many years. Conscious or subconsciously, I’m aware that I’m not necessarily what the publishing world thinks of when they think of working-class writers. But I realized I couldn’t write about my father’s death without writing about class.

My parents were pretty private about their finances, so I was gleaning a lot of information about our situation from seeing that there wasn’t money for exam fees or college application fees, so I worked a part-time job. I didn’t know what my parents made until I peeked at my FAFSA.

I wanted to work their financial situation into the book, but it was hard to be explicit when I didn’t have the data. Then I realized that it was interesting to point out that’s how a lot of us learn about how family’s situations: we deduce based on what we see, and I had so many questions and so much anxiety as a kid around money.

HB: Can we talk about the moments of comfort and peace you wrote into the book? There were these really profound moments on spirituality that resonated with me, even though I’m atheist, and I’m so glad you included your dog, Peggy! When I’ve been in writing workshops, especially when writing about trauma, I’ve seen readers respond so positively to these kinds of joyful, peaceful, transcendent moments in a manuscript. Why was it important to you to include these kinds of “breathers” in the book?

NC: I have a fraught relationship with religion myself now, but I can’t deny that because I was raised deeply Catholic, it’ll always have a certain hold on me. My mother converted to Orthodox Christianity when I was in college, and my dad followed. They had this tiny mission church that really became their family after I left home. They were nourished and loved and accepted in this little religious community.

When my father died, the whole community rallied around my mother. During the pandemic, I couldn’t be with my mother, but she had such a good network of friends who made sure she didn’t want for anything. I haven’t been part of a religious community like that as an adult—it’s rare and precious. Ultimately, I am going to be thankful that their faith was such a comfort to them and that community was life-giving to both of them.

Writing about having a dog was a way to talk about my family again. My mother loved dogs. Some of the funniest moments in the book are between her and her dog, Buster. I write in the book about taking her out during our last Christmas together, and when I arrive at her house, she says, “Hold on, I have to put on the television for Buster so he doesn’t get lonely.” And she puts on PBS and says it’s more educational!

Having Peggy, my first dog as an adult, has helped me understand an aspect of my mom. She was also a very anxious person, and dogs were one of her real comforts. All the way til the end when she was sick, Buster stayed faithfully by her side, and I know that was part of what sustained her. Writing about Peggy was also a way to write about my anxiety and its connection to my grief.

When we got her six months after my mom died, it was like an infusion of joy and chaos in our household. In my grief, for months, even when I was experiencing or witnessing joy, it was like I couldn’t access it myself. It was hard for me to feel joy was real. This is really cheesy, but when we got the dog, it felt like this wall came down. I was able to feel and experience my kids’ joy in a way I hadn’t been able to for a long time.

HB: You recently published a beautiful edition of your newsletter for The Atlantic about writing about the dead in the context of this book. That reminded me of a passage from an Alexander Chee essay—I have you to thank for introducing me to his nonfiction—where he exhorts us to “write for your dead” and to “tell them a story.” What did you want this book to say to the people you’ve lost?

NC: The greatest gift my parents gave me was always making me feel like I was enough for them. It sounds so basic, but I think it’s really rare. It’s not to say that we had an uncomplicated relationship, because we did not always agree, but ultimately, I always knew there was never anything I had to do or be or accomplish for them to be proud of me.

If there’s one thing I could say to them—although I tried to say this to my mother when she was alive—is that I know what a precious gift that is. I recognize that’s the foundation that I’ve built my whole life on, and so I hope that comes across in this book.

Hannah Bae

Hannah Bae is a freelance journalist and nonfiction writer who is at work on a memoir about family estrangement and mental illness. She is the 2020 nonfiction winner of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and she was a 2022 and 2021 Peter Taylor Fellow for The Kenyon Review Writers Workshops. You can learn more about her work at www.hannahbae.com.