Nicole Chung on the Task of Winnowing a Life Story (and the Magic of Dogs)

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

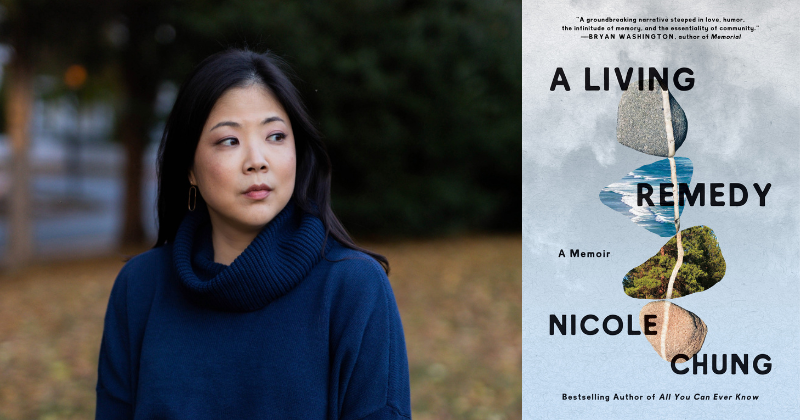

This week on The Maris Review, Nicole Chung joins Maris Kreizman to discuss her new book, A Living Remedy, out now from Ecco Press.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

On the task of winnowing a life story:

MK: Does the act of [recapping from the previous book] what readers of this book need to know change the way you look at the previous book, or your life?

NC: Maybe one way to answer is to say I was really conscious in the first book of doing the same type of work I did in this one. You’re doing a lot of that active memory work, which can be really difficult to write a memoir. And then I remember sort of folding up different memories in my head and thinking, does the reader need to know this? Do they need to know this to understand this?

This particular story, which in the case of the first book was the story of being a transracial Korean adoptee, why I decided to search for my Korean birth family, and then what happened when I did. And in some ways that book has a much narrower focus, and it almost made it easier to look at those memories and moments from my life and decide what belongs and what doesn’t.

Because it was extremely focused on this one major aspect of my life that touches on a lot of other aspects. But if it didn’t have to do with my feelings or my experience of an adoption, it got left out of that book because there was only so much it would hold. With this book it was daunting.

It was much harder, given the story I was trying to tell about my family, about how I became aware, in the way you do growing up, of money and class and your family’s situation and where you are in the world and what else is out there. All of that is slowly accumulating childhood and adolescent experience.

Then it was like, everything is relevant to this book, but I can’t write everything. Nobody wants to read 900 pages about my life. I know that. So I think the active winnowing it down was harder, but at the same time, it helped so much that I had that first book, that I had that practice doing that particular type of work. I just had a little more confidence, and maybe some of this is being an editor for years as well, in figuring out what belongs in a story and what doesn’t, hopefully without leaving the reader with too many unanswered questions.

I’m sort of building scaffolding. What do you need to follow me on this journey we’re taking? It is a very challenging thing. To your question, I do think it makes you reevaluate a lot of moments and events and maybe even relationships in your life a bit. That’s actually part of the fun and part of the scary part of the genre, I think, because it really can upend things you thought were settled.

*

On the pain and anger of not being able to be with her parents when they died:

MK: One thing about our wonderful country is that if you have an illness and you have problems with it, you are more likely to be blamed. There are times when my blood sugar is high and I feel like I’ve done something morally wrong. That’s a lifetime of being told that you have to do everything you can do all the time forever and never have a flare-up.

NC: It’s all on you, right? There’s this obsession we all have with personal obligation and responsibility. I’ve been thinking a lot about this in the way it just lets entire systems off the hook. A parallel to that is the way I blamed myself for not being able to help my father more. I could not pay for the healthcare he needed out of pocket, especially in the years when he needed it most. I just wasn’t a millionaire and I did not have that kind of money. But I blamed myself for so long, and I still have regrets. I could have not worked in publishing, I guess.

The truth is communities can do so much, but they cannot fully compensate or fill in the void of a broken safety net, the way that benefits and assistance and social programs are gatekept and means-tested and you have to prove you’re worthy. You have to prove you’re deserving and more worthy than those other people. I mean, there are so many points, not just with the healthcare system, but where the entire safety net really failed my family as it fails so many.

The thing I can’t get over again is, for me, it’s individual tragedy and loss. But it’s also a collective tragedy in this country that so many people are experiencing every day. That’s really why that was an aspect of my grief, that it almost surprised me when I realized how angry I was about this. And it was a part that I really wanted to try to face head-on in the book.

MK: One of the things that really struck me in the book is the amount of guilt you personally felt about not being able to be near to your parents as they were dying. It was physically not possible, but that doesn’t necessarily prevent you from feeling okay about it.

NC: It was just so hard, and the reasons I couldn’t be there were so different for the two of them. With my dad, I couldn’t be there right when he died because the actual moment, we did not see it coming. We didn’t know it was going to happen. But I wasn’t able to visit as much as I wanted. It was a period of life where if we were going to see each other, it meant someone was putting flights on a credit card. I want to stress that I have a lot of class and educational privileges my parents did not have, but I was in this period of life where there just wasn’t enough. And it was really hard.

And then with my mom, by then, I’m finally financially stable. And then she enters hospice as the first COVID cases are being reported. My last trip to see her was supposed to be in March 2020. And of course it didn’t happen, and she died that spring. I’ve actually been trying to brace myself, and I hope it doesn’t happen, but I wrote an essay about that conflict I was feeling at the time for Time Magazine. And an overwhelming flood of people saying, they were in the same boat, and they understood and they were sympathizing.

But I did get some comments that were like, so you chose not to be with your dying mother because people are trying to control our lives and curtail our freedoms, and you fell for it. So I have been bracing for a wave of that with the book. If those people think I haven’t said that to myself so many times, not in those exact horrible Trumpy words, but if they think I don’t have regrets or questions… Like if I’d known about COVID what we know now, or if I’d been vaccinated, or if my kids had been vaccinated, if a million other things. If they think that I don’t think about that all the time, that I won’t always live with those questions.

It was deeply painful after expecting—because she had cancer, I thought at least we’d get a warning. I would go and I would be there. Not being able to do that because of the pandemic is always going to live in me, and it’s something my kids will have to live with. That memory of all of us live-streaming the funeral from our living room. They knew that wasn’t typical. They knew that wasn’t really right, and yet it was the option that was available to us. The common thread is that I know this is true for so many people who lost loved ones, especially in those early months of the pandemic. And every time I write or speak about it, people tell me, “This happened to us too. We still haven’t had a funeral for this loved one.”

It angers me how much many people want to look away from that experience, that time and that pain that people are still carrying. But I don’t think we can or should be looking away from that. I know it’s hard to face, but I do not think we can forget that.

*

On how her dog, Peggy, fit into the book:

MK: I was so heartened when Peggy made her appearance in the narrative.

NC: We got her six months after my mom died, and you remember November, December, 2020—it was a bad time. Nobody was doing well. My kids were doing six hours of Zoom school a day and we had no idea when it was going to be over. It’s pre-vaccine. We were all just surviving, but nobody was thriving in this house.

Peggy just crashed through this wall of sadness and isolation that had been building up. We still didn’t see a lot of people. We still missed my parents, missed a lot of people we love. But when you have a dog sometimes you’re just responding to what they need in the moment. At first all I could do was react to her and that was actually really nice.

Part of my brain turned off and it was like, okay, what does this small being need? Basically, dogs are magic. My friend Jess Zimmerman told me once that golden retrievers are like pillows that love you, and it’s true. We basically trained her to be a comfort animal with lots of cuddling and hugs, and you can really rely on her for that.

I think bringing Peggy into the book became a way for me to talk about my anxiety, which is not something I’ve really written about before. I was trying to think of a way to do it that would make sense and also have some levity. And she was a way to do that because she’s such a comfort and because she makes my anxiety go down so much.

My anxiety reminds me sometimes of a guard dog—it’s just looking out for me. It just wants me to be aware. And at times that could save you, but ultimately you can live with it and be aware of it and not always be thinking about it. It was important to me to talk about that and try to make a connection, too, to my mother’s anxiety. Writing about Peggy was a surprisingly fun way to do that. So yeah, she’s great. She is the emotional center of the family.

*

Recommended Reading:

White Cat, Black Dog by Kelly Link • All the Gold Stars by Rainesford Stauffer • Mobility by Lydia Kiesling

__________________________________

Nicole Chung is the author of the national bestseller All You Can Ever Know, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, a semifinalist for the PEN Open Book Award, and an Indies Choice Honor Book. She is currently a contributing writer at The Atlantic, and her work has appeared in numerous publications, including The New York Times, GQ, Time, The Guardian, Slate, and Vulture. Her new book is called A Living Remedy.