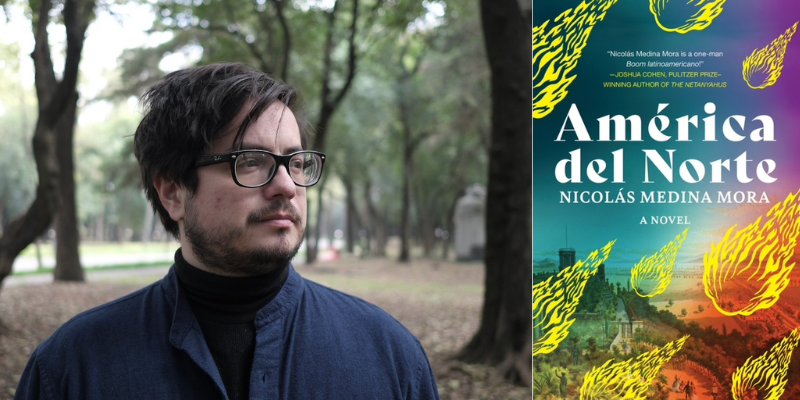

Nicolás Medina Mora on Mexico’s First Woman President and the Country’s Political Future

In Conversation with V.V. Ganeshananthan and Matt Gallagher on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Journalist and novelist Nicolás Medina Mora joins co-host V.V. Ganeshananthan and guest co-host Matt Gallagher to talk about Mexico’s president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, who will be the first woman and first Jewish person to lead the country. Medina Mora explains current president Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s history, his hold on Mexico’s political imagination, and how his connections to Sheinbaum will affect policy moving forward as he uses his last days in office to attempt 18 changes to Mexico’s constitution. Medina Mora, who is an editor at the Mexican magazine Nexos, reflects on writing about Lopez Obrador through both fiction and journalism. He elaborates on a pre-election piece he wrote for The New York Review of Books and also reads from his novel, América del Norte, in which he plays with the relationship between fiction and nonfiction.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Matt Gallagher: Claudia Sheinbaum was elected President of Mexico on June 2, and we were just talking about her status as Mexico’s first woman president and first president with Jewish heritage. She’s also a scientist who was previously secretary of the environment in Mexico City, and she had the support of the incumbent president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, more commonly known as AMLO. We’re going to get to Sheinbaum in a moment, but can you tell our listeners a little bit about AMLO, their shared party affiliation, and why he was such a beloved figure? Basically, how did things stand when the election took place?

Nicolás Medina Mora : Sure, so AMLO was elected president in 2018 in a landslide, not quite as big as Sheinbaum; Sheinbaum got 5 million votes more than him, which is really remarkable.

AMLO campaigned as a leftist under the banner of a party that he founded called El Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional, or Morena for short, and he defeated the candidates of the traditional parties that had dominated Mexican politics for the first 18 years after the end of one-party rule in 2000. An important thing to remember is that we haven’t really had democracy in Mexico until 2000. I remember the first democratic election, and AMLO campaigned as an outsider because he had left the traditional parties, but he has had a long career in Mexican politics.

He was mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2006. And before that, he was a card-carrying member of the one party that we had before, the authoritarian party of the institutional revolution, or PRI. And so he’s a complicated figure. I don’t doubt his leftist convictions when he governed Mexico City; he was a perfectly reasonable social democrat. He became beloved and popular by passing welfare measures, such as a pension for old people, for elderly folks. And generally he rejected the traditional pomp and circumstance and, implicitly, grift that people have come to associate with Mexican politicians. He would be driven around in a Nissan Tsuru instead of an armored SUV, things like that.

And then he ran for president in 2006, and he lost by less than one percentage point to the right wing candidate, Felipe Calderon, and he and many of his supporters believed that fraud had been committed against him, electoral fraud. And so AMLO, at that point, became soured on the institutions of what had come to be known as democratic transition, this period of moving away from the one-party state towards a pretty patristic democracy. And he kind of became bitter in a way, at least this is this my view.

As president, he remained extremely popular. He has approval ratings that, depending on which polls you listen to, range from 55-70%. But his policies as president have not always been left wing, and sometimes I think, frankly, reactionary. He has empowered the military. He has declined to raise taxes. And so, we arrive at the election with a very popular president, who had insisted discursively that he was leftist, but he was governing in a complicated way that we can talk about more later. And he anointed as his successor: Sheinbaum, who was at the time mayor of Mexico City. And I think everybody thought she was going to win, everybody who was serious, but nobody really anticipated the extent of her victory, just the margin by which she won, we can talk more about that later, but I think that’s more or less where things stood.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: I didn’t realize the margin was so huge. So when I first read about Sheinbaum, I thought, “Oh, it’s a Jewish woman who is also a progressive climate scientist! I can feel good about this! I would love some news to feel good about!” But in a piece he wrote for The New York Review of Books, which was published on April 7 before the election, you offered this much, much more complicated take on her, which I really appreciated reading. I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit more about her background and what about her connection to AMLO that gives you pause.

NMM: Sure, so Sheinbaum is the granddaughter of Jewish refugees who fled the Holocaust, on both sides of her family. She grew up in an upper middle class family of academics in Mexico City. Her parents are also scientists, and her upbringing seems to have been more leftist and secular than religious. There’s a video of her that her campaign circulated of her playing and singing this genre of leftist Latin American songs when she was 8 or 9, I forget exactly her age.

And then she entered politics as a college student in Mexico, campus politics are different from the United States, they are much more about national politics than they are about the university itself, and she joined a group that later became the youth wing for the leftist party that AMLO left to found Morena later. And there’s a photo of her protesting the North American Free Trade Agreement when she was doing graduate research at Stanford. So, she has been involved in leftist politics from a young age and throughout her whole life, and, from a very early time in her career, she became tethered to AMLO.

Her first public position, her first position in public life, was as Secretary of the Environment for AMLO’s government in Mexico City. Then after that, she was elected head of the Mexico City borough of Tlalpan, which is in the south of the city, which is kind of like borough president in New York, if you will, and later, when AMLO was elected president, she was elected mayor of Mexico City, his old perch.

And the reason why her relationship with AMLO gives me pause is that, yes, Sheinbaum sounds great on paper, and everybody that I know who has worked with her thinks very highly of her and thinks that she’s not to be dismissed as a mere puppet of the president. But the problem is that the party that they share is this collection of contradictions. It’s kind of like the Congress Party in India. It’s just this giant thing where there’s all of these different factions, it’s different in different regions, it has people who are straight up communists, and people who are just refugees from the other parties that were sort of destroyed by its electoral success. And the only thing that holds it together is loyalty to AMLO, at least so far. That may change.

So the problem is that you worry that Sheinbaum may, partially because she seems to be sincerely a true believer in this man, and partially also because she needs him not to declare her a traitor to the motherland in order to govern effectively, that she might not be able to deviate from some of his more, shall we say, reactionary policies. AMLO is obsessed with oil. There’s this old commonplace in Mexican politics, in the 1930s, that oil is the blood of the nation, because the one socialist president of the old regime, Lazaro Cardenas expropriated the foreign oil interests, and for many years Mexico enjoyed really remarkable economic growth thanks to oil. That’s no longer the case; the state oil firm is completely decrepit.

But AMLO, nonetheless, has been building this refinery, this new oil refinery that has cost an absurd amount of money and has yet to refine a single barrel. But setting aside the kerfuffles with the construction of this thing, one has to wonder who in their right mind builds an oil refinery in the year of our Lord 2024? Given what we know with climate change, it seems completely suicidal.

So we seem to be facing this paradox: We just elected a climate scientist as president, and yet she’s unlikely to cancel this refinery, or move away from this oil first energy policy. Partially because, again, she seems to sincerely believe in AMLO, and AMLO’s ideology, and then also from a more pragmatic perspective, because she really can’t afford to alienate him. So that’s, I think, one thing that gives me pause. We have a candidate, now president-elect, who has many things to like, but who is going to enter the National Palace in a context that won’t necessarily allow her to govern in the way that, I think, her more progressive supporters would hope she will.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Keillan Doyle.

*

América del Norte • Where Next for Mexico? | Nicolás Medina Mora | The New York Review of Books • Nexos

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 32: “Claire Messud on Blurring Family History and Fiction” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 17: “Ed Park on Korea’s Past, Real and Imagined” • “Mexico’s outgoing president pushes ahead with plan to fire 1,600 judges” by Christine Murray | Financial Times • “Mexico’s bloodiest election in history sends new asylum-seekers to the US border” by Caitlin Stephen Hu, David Culver, Norma Galeana and Evelio Contreras| CNN • The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen