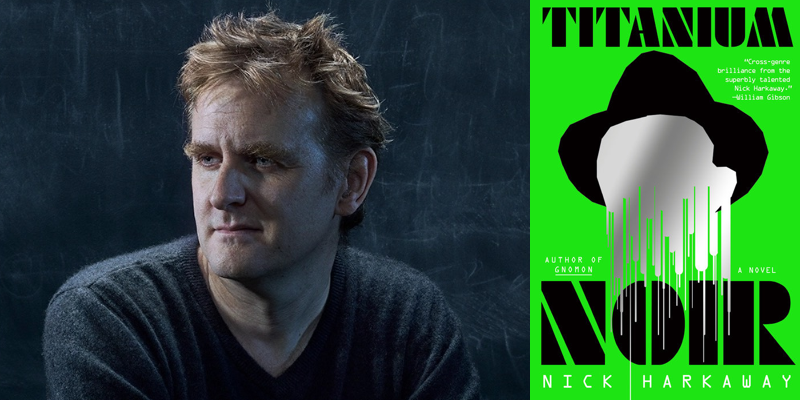

Nick Harkaway on Not Going All The Way Into The Shadows

In Conversation with Rob Wolf and Brenda Noiseux on the New Books Network

According to Merriam-Webster, noir is “crime fiction featuring hard-boiled, cynical characters and bleak, sleazy settings.” The Cambridge Dictionary says noir shows “the world as being unpleasant, strange, or cruel.” Nick Harkaway new novel Titanium Noir has all that but with a twist—rather than the fedora-wearing detective hired by a woman who’d just as soon stab you in the back as love you, the first-person narrator is P.I. Cal Sounder, hired by the police to help investigate the murder of a 7’8”, 91-year-old man who by all rights could have lived several more centuries.

Sounder’s specialty is investigating crimes against Titans, the one percenters among one percenters, whose access to an exclusive medical treatment known as Titanium 7 enlarges both their bodies and their lifespans.

The story is set hundreds of years in the future, when such miracle treatments become possible, but the book also sends roots into the past. The murder weapon, for instance, is a .22 Derringer, a small handgun not too different from the weapon used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln.

“Killing someone with a gun is noir. Every poster of a noir movie is someone with a gun, whether it’s a shadow with a revolver or a kind of Rico Bandello in Little Caesar. The gun is bound up with noir and vice versa,” Harkaway says.

From the episode:

Rob Wolf: Stefan Tonfamecasca controls something called Titanium 7. Tell us about Stefan and Titanium 7.

Nick Harkaway: Stefan is the big guy—I mean, literally huge because when you take Titanium 7, not only do you get younger—it resets your physical age to about 17—you also get 20 percent bigger each time you take it, and all the super-rich take it. Your Musks and Zuckerbergs all end up after two- three- four hundred years being 14 feet tall and commensurately broad.

They’ve become physically immense. And Stefan is the original Titan. He’s either invented it or he bought the company that invented it, but no one knows which because this information is, to some extent, lost in the mists of time. The only way you would know the answer would be through history, which by definition, if you’re a Titan, you control or can edit.

RW: It’s interesting that you talk about the Titans being the preservers of memory because Titanium 7, when it rejuvenates them, can also damage their memories, which makes for an interesting crime story.

NH: This is part of the game for me. What you have is an unreliable history in every direction. If the record belongs to the very wealthy and the very wealthy can’t be depended on to remember things, you have an interesting societal disconnect.

Brenda Noiseux: The Titans are so distant from the non-Titans and part of that may be because these are the ultra-wealthy and they’re only 2000 of them in the world. Is this a commentary on immortality or did you have other designs in mind?

NH: It’s not an on-purpose discussion of immortality. I always think there’s an immediate rush when people start writing about longevity treatments that there’s something wrong with that, that it comes with inherent disadvantages, that it distances you, and it takes you away from who you really are. And I always find that a little bit frustrating. At the end of the animated movie of Hercules, Hercules has to decide whether or not to become a god, and I’m kind of like, say yes because you can then do incredible things for your friends. It’s not necessarily a zero sum game.

With the Titans I gave a soft limit on how long they can go on taking the drug because when you’re telling a fantastical story like this, you have to indicate the boundaries. There have to be rules which you can lean into because you’re otherwise in impossibly unfamiliar territory. So the thing is, if you make a human frame bigger and heavier, there’s no way that guarantees perpetual expandability. Really large animals in our gravity using one heart have a limit on how big they can be. That’s why whales live in the ocean, not rolling around on grassy plains somewhere, and why the dinosaurs had different ways of dealing with scale. So the square-cube law applies. It’s not purely me malevolently saying there’s a downside to extended mortality. It is about recognizing the limits of the real.

BN: Were there elements of noir that were a must-have for you or any elements that you wanted to stay away from?

NH: I realize increasingly that as I write, the first thing that I need is the mood. The mood defines the edges of the world. It tells me what the character is going to be like and so on. And I wanted this to have that feeling of shadows and cynicism and the possibility of better things, which you have to constantly strain for and you maybe never get.

There’s a kind of grotesquerie of violence in some noir fiction which I can’t go to. I can edge up against it and I can indicate it. … but it’s not where I’m comfortable. So there’s this sense of not quite going all the way into the shadows, however dark it becomes. There’s always a way back.

RW: What was it like having a dad (John le Carré) who was very successful as a writer? Did you share your writing with him? Did you compete with him?

NH: I can’t answer that question because I never had anybody else for a dad. So I don’t know what it would be like not to have that. Did we compete? No. I mean, how could you? But did he perceive competition between us? Weirdly, yes, absolutely. He went and did an event at Cambridge University. He was an amazing performer. He was one of those people who can absolutely captivate a room. And after this event, one of the tutors came up to him afterwards and said, “I’m such a fan. I loved hearing you speak. And if I could make so bold, I also read your son’s book and I loved it.” And he was like, “Oh, that’s marvelous.” And he came home and he was grumpy for days. My mother was howling with laughter. She was like, “You have to give him this one. It’s not like that changes the fact that everyone thinks you’re a megastar.”

He wasn’t being ungenerous. He was just terrified. I was like, “Are you kidding? Have you seen, the Golden Daggers and others awards dotted around the house?” It was a kind of a goofy moment between us. But I could tease him about it. He knew it was ridiculous, but he kind of still felt it, which was charming. Did we ever talk about writing? Very rarely directly. He never sat me down and gave me a masterclass. It wouldn’t have occurred to him. He would have thought that was terribly rude. He would have said it would spoil my writing because he could only talk about how he wrote, not how I wrote.

Did I show him my work? Absolutely. He always claimed to have looked at it, but usually claimed not to have properly read it. My brother Simon said to me recently that, “Yeah, sure, he claimed not to have read it, but he was remarkably well acquainted with everything that happened in your books.”

__________________________________

Nick Harkaway is the pen name of Nicholas Cornwell. As Harkaway, he is the author of the novels The Gone-Away World, Angelmaker (which was nominated for the 2013 Arthur C. Clarke award), Tigerman, Gnomon; and the non-fiction The Blind Giant: Being Human in a Digital World. He has also written two novels under the pseudonym Aidan Truhen.

New Books Network

The New Books Network is a consortium of author-interview podcast channels dedicated to raising the level of public discourse by introducing serious authors to a wide public via new media. We publish 100 new interviews every month and serve a large, worldwide audience. The NBN is staffed by Founder & Editor-in-Chief, Marshall Poe, and Co-Editor, Leann Wilson. Feel free to contact either one of us for more information.