New Yorker Cartoonist Barry Blitt: How Far is Too Far in the World of Political Satire

The Author of Blitt, in Conversation with Kerri Arsenault

The second time I ever spoke to renowned New Yorker cartoonist Barry Blitt, whose book Blitt published this week, was at my house, during our annual Memorial Day party, under the Khousa dogwood tree. Our town, Barry’s and mine, is a small rural Connecticut town of about 1,200 year-round residents and I am the designated Memorial Day party-giver because the parade ends basically on my front lawn.

Barry and his wife Angie had just purchased Arthur Miller’s former house in Roxbury. It’s a modest home on the corner of a dirt and a paved road, a little outside of town. Miller had built a small writing cottage on the top of a knoll near the house, within eyesight of Barry’s studio. It’s where Miller wrote Death of a Salesman.

That Memorial Day, Barry sat on the granite slab bench sketching Graydon Carter, who was drinking a Pimm’s Cup. He asked Barry about his new house. The 40 or 50 people gathered in my yard were chatting in the early spring sun, and in between drinking my own Pimm’s Cup, I caught a little of the conversation between Barry and Graydon.

“Oh, it’s great,” Barry said. “Arthur Miller built a little writing cottage in the backyard. We’re going to bulldoze it and put the pool there.”

Graydon’s face turned a dull gray. “No!” he said.

Barry just smiled.

Barry considers himself a wisecrack, but his humor can be hard to access when you first meet him. He comes at you sideways, but it’s not because he’s mean. It’s because he’s sensitive, at least according to his wife.

*

Kerri Arsenault: What makes you laugh?

Barry Blitt: Are you serious? Awkwardness, when people are uncomfortable.

KA: The first time we met you tried to make me feel uncomfortable. I thought, I don’t know if he’s funny or if I want to murder him.

BB: That’s great!

KA: So you succeeded.

BB: I was probably uncomfortable myself.

KA: Why? Meeting new people?

BB: Yeah.

KA: When you draw, are you trying to make yourself laugh?

BB: Yeah. I’m trying to make myself laugh.

KA: Not other people?

BB: Yeah, if I come up with a funny idea, it’s like, Oh boy, this will really make someone laugh.

KA: But you have to laugh first at it.

BB: Yeah. That’s how it works, I’d imagine.

KA: You’d imagine? I guess writing is similar in that way.

BB: Please do not compare me to writers. Sorry. I’m sure writing is the same thing, and I’m sure making music is the same thing. You’re trying to entertain yourself.

KA: And it ends up entertaining somebody else.

BB: Yeah. Ideally.

KA: Because otherwise you would just draw for yourself.

BB: And that would be fine, I guess. It must have been frustrating being someone like Coltrane, coming up with crazy things first… and you know it’s good, but no one else does. Thank god, I’m not in a position of being a risk taker.

KA: You’re not?

BB: Yeah, to carve a new art form, that would be tough. And the hours. That would be hard. But just to make cheap, easy jokes. It suits my temperament fine. I’m not a genius.

KA: Do you think cartoons get away with a little more than the written word?

BB: Yeah, you can.

KA: Why is that?

BB: Because you’re putting it in quotations, you’re putting it in parentheses. It’s like cartoon characters on King of the Hill or The Simpsons or Family Guy, I guess. You can do things there that you can’t seem to do in writing. And why is that?

KA: That’s my question.

BB: I guess I’m not sure.

KA: Do you mean those parentheses say, this is not real so I can make more fun of it?

BB: Yeah, you can say certain things because it’s a cartoon to start with. It’s like there’s a contract with the viewer that this isn’t real.

KA: Except for a few cartoons…

BB. Right, Paris, what is it called again, where they shot all those French… What’s the name of it? Hebdo or something like that?

KA: Charlie Hebdo.

BB: Right. I guess they didn’t have thick enough parentheses.

KA: Or the Danish cartoons.

BB: Right. The Danish cartoons. I remember South Park did a Mohammed thing, probably we don’t want to go here, but they did an episode where they had to depict the prophet and they really tread close to the line there, but neither of them got shot.

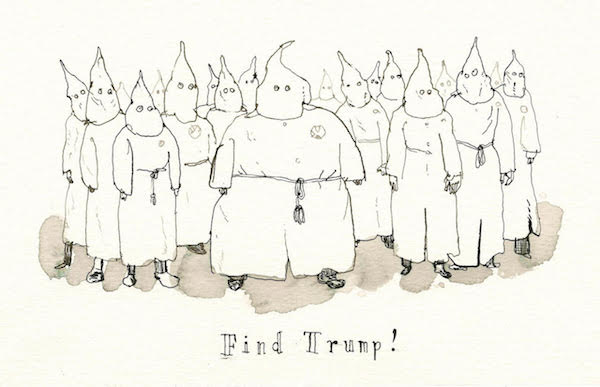

KA: Speaking of the lines, is there a line you won’t cross?

BB: Yeah, I was just talking about that with someone. I mean, I think a lot of cartoonists or satirists think that what their job is, or what amuses them, anyway, is to try and find the line and see how far they can step over it. Or just find it, you know? That’s what it is. It’s like a mischievous kind of thing. Like if you were in third grade and are trying to see what you can get away with.

KA: Françoise Mouly, your editor at The New Yorker, seems to put the line way out there for you.

BB: She doesn’t put it anywhere. She just says, “Don’t self-edit.” There were a few times, or a couple of examples… where I did one about The Producers, on Broadway, Mel Brooks’s, The Producers, and my first thought was to have an audience full of laughing people and just Hitler sitting there scowling. But I self-edited. I thought, They’re not going to want me to depict Hitler. I was so naïve then. That was before the [Obama] fist bump cartoon. Hitler was my first genocidal maniac that I had on the cover of the New Yorker. I thought, they’re not going to want to show Hitler, so I did a skinhead, like a Nazi skinhead, and then I cut it out and stuck it over the Hitler on my sketch, and I showed it to Françoise and she said, That’s a funny idea, but wouldn’t it be better if it was Hitler? And I said, you’d let me do that? And I pulled it off. I think it was around then that she said, “Don’t self-edit.” So, I’ve shown her things that a man shouldn’t have to see, or woman, I’ve shown her some very tasteless sketches.

KA: David Remnick said in your book that you are “a deadly satirist, quick and merciless.” You’re merciless toward yourself sometimes.

BB: Absolutely.

KA: I wonder if turning your deadly eye on yourself is where humor comes from?

BB: That’s what my shrink says. Maybe we don’t want to go here.

KA: We definitely do.

BB: I was talking to my shrink about a reunion that’s planned with high school friends, and I suddenly thought of these people I hate, and I don’t want to go to it because when I remember them, I remember these people I was friends with, and most of our friendship or our relationship was just about insulting each other. I don’t want to go back to that. I don’t want to be in a room with those people. And my shrink posited that it’s not them, it’s not their opinions I’m worried about. It’s my own opinions that they’re confirming, my own bad opinions about myself, and he said, that might be where your work comes from, the fact that you’re harsh on yourself and harsh on the world.

KA: It would be awkward to pat yourself on the back all the time, too.

BB: I know plenty of people who are very comfortable doing that. I mean, I’ve never done a book about myself before, and maybe I shouldn’t have asked people to write about me, but the editor suggested we get some essays written by people in the field. As the essays started to come in they were all, of course, laudatory because you’re asking someone to write about you for your book, and they’re going to…

KA: They’re not going to write, “He’s an asshole.”

BB: Right. There is an art blogger who writes really harshly about me, and I thought it’d be funny to include him and have him write an essay.

KA: Absolutely.

BB: But the editor didn’t seem to think that was a good idea.

KA: Why does he hate you so much?

BB: He doesn’t like the way I draw, which there’s a lot not to like. He showed some examples of my work and compared it to… I had drawn a crowd scene and he compared it to a great New Yorker artist of the past, and yeah, it was very harsh. When I first read about myself on his blog, I was really taken aback, but I very quickly didn’t give a shit afterward

KA: I didn’t know people wrote reviews of political cartoonists.

BB: Everybody’s got an opinion, especially when you’re in the New Yorker and when you’re published a lot.

KA: It seems like you and your work are two sides of the same coin. Does that make sense?

BB: Yeah, I guess so. I don’t see how the work can be separate from who you are. I don’t think I could do uplifting work or spiritual work because there’s not a spiritual bone in my body.

KA: You came close—you drew the New Yorker cover memorializing the Charleston massacre, the ones with the nine birds flying out of the church.

BB: Right. That cover surprised me as much as anyone.

KA: Newtown is so close to here. Did you ever submit a cover for the New Yorker after what happened there?

BB: I don’t remember, but probably not. They just asked for Las Vegas sketches and I sent in a couple. Because there’s been a problem with people not standing for the anthem, I did a bunch of congressmen, Mitch McConnell and all those guys, and senators, and Paul Ryan, they’re always singing the National Anthem with their hands over their heart and there’s a flag in front of it, it’s an NRA flag. They didn’t go for that. And then I did another one was just a street of gun stores and every store had handguns, ammunition, rifles, and at the end of the street there was a little funeral home, just very small. They didn’t go for that either.

KA: It’s interesting that you could take a dark event like Las Vegas or Charleston and get a small giggle out of it.

BB: I’m not showing dead people or anything.

KA: No. But you are making fun of people’s fears.

BB: That’s funny. That wouldn’t surprise me. I’m a fear-based organism.

KA: I don’t mean it’s about fear, but about making fun of us and our fears. Like politics. You do a lot of politics. And lately, most of us are terrified of politics.

BB: Well, politics has become popular culture. I don’t know if it always was. I guess it must have been. I started doing political stuff around the time of Monica Lewinsky and that stuff just because I got asked to do it. I was doing cartoons for Entertainment Weekly regularly. I was more of a music and movies guy.

KA: The Internet certainly made the culture of politics more mainstream. Have technology or the Internet changed cartooning?

BB: So many people have access to it.

KA: Politics or cartooning?

BB: Access to everything with the Internet. Our culture seems more connected. I mean, the Monica Lewinsky thing was just gossip. It could have just been a Hollywood scandal. And Donald Trump’s in the White House.

KA: How do you avoid clichés in your art while also using them?

BB: A cartoonist deals in clichés. Some are offensive, but some aren’t offensive. But you tweak them if you can. I did one that when Steve Jobs died, but I had him at heaven’s gate with St. Peter on an iPad. There were a number of cartoonists who did the same idea, and now it’s very offensive to me how many people do that. I sure wouldn’t use it again. But there were a certain number of people using St. Peter on an iPad. And now, when anyone dies, there’s often cartoons of that. But when I did that one, there was one cartoonist who did a real scathing cartoon about the fact that everyone was using that. Steve Jobs himself was a Buddhist and didn’t believe in that anyway. But you take a cliché and show it in a way that hasn’t been used before.

KA: Then it becomes a non-cliché?

BB: It’s still a cliché, but you sort of isolate it and put it a snow globe or something.

KA: David Remnick said in your book that he imagines a dozen mini yous in the woods of Connecticut, churning out all these covers. For those who don’t know what it’s like in Roxbury, in your daily life, there’s not a dozen little Barrys, right?

BB: There are not, thank god. Compared to the amount of work cartoonists are doing, there must be hundreds of them, because this really doesn’t take dozens of people to do. I don’t know how many covers I do a year, but maybe it’s six or eight, and I certainly pitch ideas for most weeks, or lots of weeks, and I send lots of ideas, but it’s still not that much compared to what cartoonists do, what syndicated cartoonists do. I work fast, that’s the thing.

KA: If you are told, we need something quickly, can you put together a cover?

BB: Yeah. I did the Brexit cover, after the voting results were announced on a Thursday night.

KA: Is that the one where the guy is walking over the cliff?

BB: Right. I had about an hour and a half to come up with the idea and do the final art, and it was done in a frenzy. I can’t really remember any of it. I was in a blackout or something.

KA: To know what’s going on in the world, do you watch TV, or the news, or what?

BB: You’re just aware. I don’t watch TV. I go to several websites, more than several.

KA: Since you live in what was once Arthur Miller’s house, I was reading something on the National Endowment for the Humanities website about him. It said: “Miller has been creating characters that wrestle with power conflicts, personal and social responsibility, the repercussions of past actions, and the twin poles of guilt and hope.”

BB: That’s me. Me, me, me, and me.

KA: Or the polar opposite.

BB: I’m sure in every way possible.

KA: But you do deal with characters that wrestle with power conflicts and ideas of personal and social responsibility.

BB: That’s just because that’s my beat—people. But he and I have nothing in common.

KA: Except dealing with power.

BB: Well, that’s issues of power between people. It’s not the same, I don’t think. And I don’t think he would give me eight minutes of his time. I would start talking, and there might be a wry smile if I said something funny, but then…

KA: It would be over.

BB: It would be totally over, right, yeah. I’m sure it’s an affront to him that I’m living in this house.

KA: I won’t say anything.

BB: Luckily, he’s dead. And I’ve tried to go into his shed there where he wrote Death of a Salesman. It’s up over the knoll out there. And I thought maybe I’d get vibes. I needed an idea once, but I felt nothing. There was mold and I was sneezing. That’s about as inspirational as it got.

KA: I’m not going to ask that much about your process because it’s in your book.

BB: My prostate?

KA: Do you want to talk about your prostate?

BB: It seems to be leveling off. It seems to be fine so far. My father is dealing with issues.

KA: Somebody in the book, I can’t remember who, said making cartoons was like a sausage-making process.

BB: Yeah, you don’t want to see it. There are plenty of people who probably can talk about their process. That Brexit cover had to be done quickly. I don’t know where the idea came from. I got an email, it was sent out to a bunch of artists saying, If anyone has any Brexit ideas, we’re going to hold our cover that we sent to the press. And I just thought, it’s so late. I just walked into my studio and had two ideas by the time I was there. I don’t know where they come from and I don’t want to know.

KA: I want to talk a little bit about music because it seems like an important part of you and your life.

BB: And for everyone our age, but yeah.

KA: But you take music very seriously. You play keyboards.

BB: I’m an amateur. I like to play. I play in front of people, but whenever it’s recorded, it’s shit. I’m not a good musician.

KA: What is it you like about playing keyboards?

BB: You’re accomplishing something and yet there’s no result. I mean, you’re playing and it happens, whereas drawing, you’re working towards a drawing and then it’s there and it’s set, there’s a result. It’s printed or in a picture frame, but it’s there. The playing just seems like it’s always a work in progress, and whenever I record it, I regret it.

It’s also a connection. The first time I met you and I wasn’t friendly, well, it’s much more fun for me to go get together with friends and play music than it is to just get together and meet people. A lot of my friends are fellow mediocre musicians and we get together and we play. And if we’re not playing, we talk about playing.

KA: You just said that you regret when you record your music. Do you also regret things you draw?

BB: I totally do. Most of the time, yeah.

KA: Why is that?

BB: I don’t know.

KA: Maybe because it’s so permanent, which is why you say you don’t like recording?

BB: Yeah. I just see what it could have been.

KA: Do you look at your work after its published?

BB: My publisher gave me a hundred copies of my book and I really haven’t looked through it. I looked quickly through it when it first arrived and I went [gasping sound]. I’ve read bits of the essays. I would have caught the Henry Miller thing [in his book, it says he lives in Henry Miller’s house not Arthur Miller’s house] if I had looked at it, but it’s hard for me. I can just see what I should have done.

KA: What do you when you are not inspired?

BB: I will play the piano too much, or I’ll be on the Internet just surfing and going to hockey sites and then going to the Drudge Report and going to Memeorandum and then checking my email and back to the hockey sites.

KA: Do people ever make suggestions about what to draw?

BB: For a while I was getting a lot of emails from people suggesting ideas to me.

KA: Is that good or bad?

BB: It’s generally bad. No, it’s always bad. I mean, there was one guy who gave me an idea that I used. And there’s this poet, I forget his name, and I wouldn’t want to say his name, but I looked him up and he’s a well-known poet, he’s an old guy now, and he started suggesting ideas that were unusable. I mean, often the visual doesn’t translate from someone who’s verbal. Anyway, he was like, put Trump here.

KA: He was giving stage directions…

BB: Yeah, like, there’s a milkshake machine over here [said in a voice like Darth Vader]. It wasn’t that, but it was this crazy shit. I answered the first one and then he kept sending more and then he wouldn’t even tell me he had an idea. He would just write an email saying, Trump is standing here and there’s a… So by that time, we were familiar, so he was just spitting out ideas. I stopped answering him, and I haven’t heard from him lately, and that’s probably a good thing. They were coming every day for a while.

KA: That could be a whole cartoon unto itself.

BB: This is the last email the poet wrote to me: “At his Oval Office desk, an eight-armed Trump, see Sheila The Destroyer, whose middle index fingers point every which way. Possibly in a Stetson hat or a Make Me Great Again cap. On the desk, possibly upside-down, a desk whatchamacallit reading ‘The buck stops here.’ It’s apropos Trump today that he won’t own the destruction of Obamacare.” Yeah, getting lots of those from him.

KA: Wow, that’s pretty detailed.

BB: I was getting a lot of those from lots of people, but this guy, he was pretty reliable.

KA: Finally, what exactly is it that compels you draw Donald Trump (aside from the obvious)?

BB: I don’t know what to say about him. Just that every picture of him is a picture you want to draw. Anytime I see a picture of him, every angle, the back of his head is amazing. The side is great, like a seven-eighths view. You can’t see much of his face. There’s lots of stuff happening. Lots of stuff cascading. It’s amazing.

__________________________________

Kerri Arsenault

Kerri Arsenault is a literary critic, co-director of The Environmental Storytelling Studio at Brown University; Democracy Fellow at Harvard’s Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History; fellow at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia; contributing editor at Orion magazine; and author of Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains. Her writing has been published in the Boston Globe, The Paris Review, the New York Review of Books, Freeman’s, the Washington Post, and the New York Times.