New York City's Block-to-Block Inequality is As Stark As Ever

Lauren Sandler Navigates the Two Maps of NYC

There have always been two maps of the city: one a transparency laid over the grid familiar to privileged New Yorkers. You’d only see the hidden city—the one lined with mismatched linoleum squares, smelling of garlic and cologne—if you lived or worked in the social services system.

I traversed both overlaid cities as I was reporting a book about one young woman’s year navigating life as a new mother, a woman I call Camila. I met her a few weeks before she went into labor in a Brooklyn homeless shelter. The shelter, and its soup kitchen, was mainly run by volunteers, but they stopped coming once the coronavirus threat became a dire reality; it closed its doors in mid-March. Long before then, I would join the residents at the WIC offices they’d travel to for regular appointments, and the welfare offices where they’d wait for days on end to settle a single check, and the NYCHA offices where they’d vainly apply for subsidized apartments, and the bodegas and unrenovated supermarkets where they’d scan EBT cards for food, and the miles of subway, and buses beyond the subways’ last stops, where nostalgia could be a magnet to childhood homes when a Section 8 check used to pay the rent. And then I’d go home, following the map back past natural wines and butcher steaks, to my kid’s music lessons and my own mortgage payments.

Long before the current pandemic, Camila brought her baby back to her room at the shelter on a formerly industrial block of Fourth Avenue, near some of the finest brownstones in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Fourth was where McDonald’s planted its golden arches in Park Slope, both for the cheapness of the lot and the budget of the Brooklynites it wished to draw. A few decades later that McDonald’s was razed, after the neighborhood was rezoned for luxury towers, and the red and yellow plastic replaced glass and steel of a residential building that offered stroller valet service in addition to wine refrigerators in every unit. The cheapest condos in the building started at $1.3 million—though if you wanted a view with what the developers called “unlimited horizons,” it cost $2 million more. Several blocks up Fourth, a two-story institutional rectangle of a building sold for $25 million to a private developer. Until the sale, it had been the area’s Medicaid office. A block south, a new rental building offered a pet spa and a roof deck with cabanas and outdoor showers, where one-bedrooms cost $4,000 a month.

The borough that immigrants had once fled as soon as they’d climbed up into the American middle class was becoming a gated community. And yet plenty of people were still from here. Plenty of people bought their groceries at the local hold-out supermarket on a gentrified avenue—people who’d never stepped into the massive new Whole Foods nearby. But the low-slung brick building that housed the old market was sold to developers, too. It was pretty much the only place in the neighborhood the women at the shelter walked to, beating a triangular path between their temporary residence, the hardware store, and the subway up on Atlantic.

Camila may have shared the same sidewalks with denizens of a bizarre parallel economy, but she acted as though it was an unseen dimension to her. Similarly, few people I knew through my own relatively privileged network even knew there was a shelter on Fourth—even if they frequented the boutiques on Fifth, or the new bars and restaurants on Third. Just as no one I knew in New York seems to know if they lived around the corner from one of the 18 welfare offices in the city; 11 of which have closed since the virus hit New York.

Little did I know that, as my book was being published, that I had drawn a map that many readers themselves would need to follow.

Welfare offices were renamed “job centers” during the Clinton years. I’d passed their hulking architecture for years, never once stepping inside until I began accompanying Camila into their dysfunctional realm. In boom times at the Waverly Job Center in Manhattan, on Fourteenth Street, the only nod to employment I saw was an empty bulletin board with the word “Jobs” tacked on it, dangling askew. It was a gulag block of a building, its mid-century teal panels streaked with age. The city had changed, the neighborhood had changed, but this block remained one of the few where people of color crowded the gum-spotted pavement outside, queuing to be admitted into waiting rooms. Purgatory in the form of vinyl chairs, Venetian blinds, fluorescent lights.

It was better than the now-shuttered DeKalb Job Center in Brooklyn though, where the vestibule reeked of stale cigarettes and was tiled in 1970s gold and avocado. Wood-grained plastic paneled the elevator, the same untouched vintage as the entrance tiles. Inside, the air was redolent of weed, urine, and the body odor of the man rocking back and forth in the corner. Around the corner, there were grain bowls and Edison bulbs at the Stonefruit café. Regulars at either place seemed entirely unaware of the other.

Gentrification meant this schizophrenia was lived across streets, threaded through neighborhoods, blanketing vast portions of the city. Different cities sometimes inhabited not just on the same block but in the same building, where invisible borders snaked up fire escapes and under drywall. The marbling was obvious from the sidewalk, if you chose to look. But in our suddenly defunct gilded age, it seemed rare that anyone did. This is New York, where the disparate ends of our inequality spectrum live pressed together, the setting of a dystopia where real lives were lived as tourists took selfies.

The news has changed; the transparency is suddenly becoming visible to people who never expected to see it first-hand, even if they’d known where to look. One map will be dotted with ghosts, another, with resented realities. Some hallmarks of gentrified New York will raise their metal grates to reopen after this moment in our history passes. Some won’t. One thing is for sure: the New York many people didn’t see in times past will be overlaid on their own personal maps of the city in the months and years to come.

Little did I know that, as my book was being published, that I had drawn a map that many readers themselves would need to follow. And that the worst of systemic gridlock, and the inability to offer housing and subsistence as a basic right, would be unimaginably multiplied. Thousands upon thousands of people who never expected to waste away their days in the hidden waiting rooms of New York’s hobbled social services system. It never had to be this way. Now here we are.

Welcome to the other New York; it’s been here all along.

__________________________________

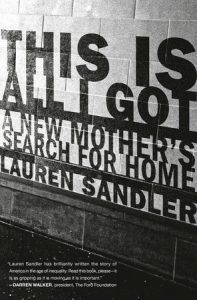

This is All I Got by Lauren Sandler is available via Random House.

Lauren Sandler

Lauren Sandler is an award-winning journalist. She is the bestselling author of This Is All I Got, One and Only: The Freedom of Having an Only Child, and The Joy of Being One and Righteous: Dispatches from the Evangelical Youth Movement. Her essays and features have appeared in dozens of publications including Time, The New York Times, Slate, The Atlantic, The Nation, The New Republic, The Guardian, and New York. Sandler has led the OpEd Project’s Public Voices Fellowships at Yale, Columbia, and Dartmouth, and has taught in the graduate journalism program at NYU, where she has also been a visiting scholar. She was Poynter Fellow at Yale and a fellow at MacDowell.