New York City, the Perfect Setting for a Fictional Cold War Strike

On Collier's 1950 Cover Story, “Hiroshima, USA: Can Anything Be Done About It?”

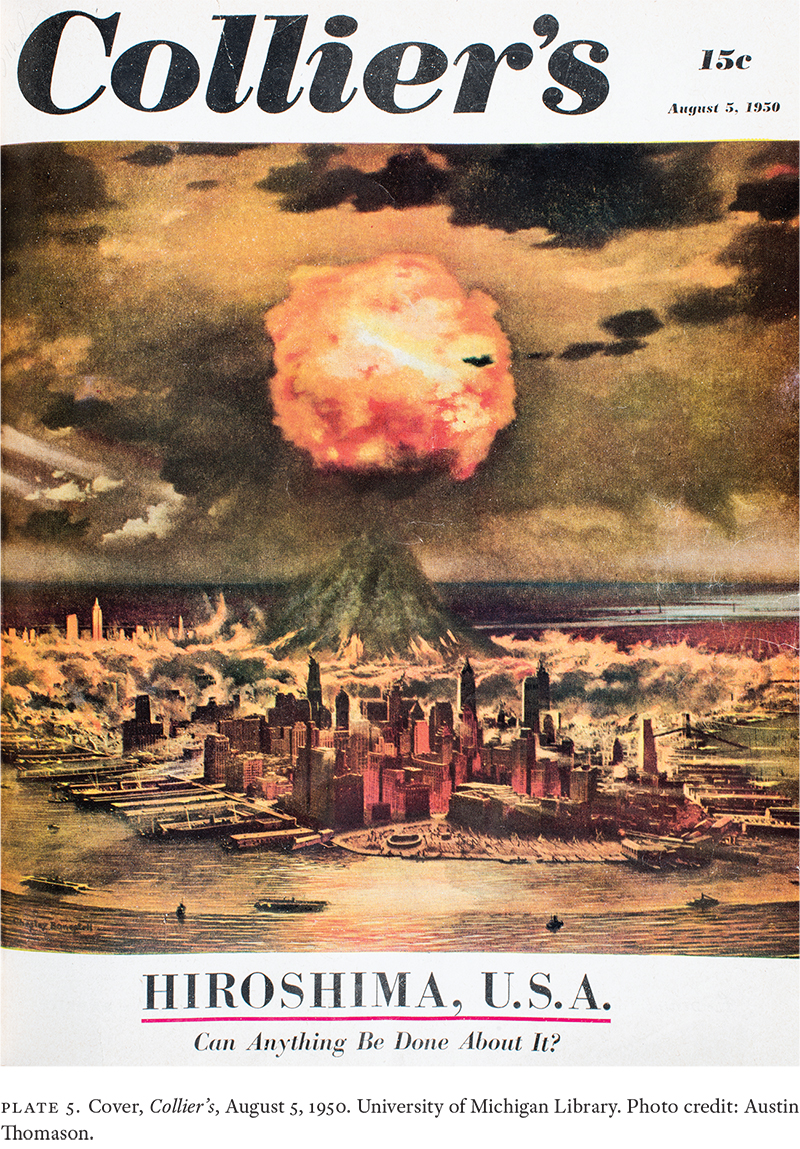

On August 5, 1950, the popular weekly magazine Collier’s featured a chilling story titled “Hiroshima, USA: Can Anything Be Done About It?” Styled as a documentary yet entirely fictive, the lavishly illustrated article offered a painstaking account of a terrifying fate: the aftermath of a successful Soviet strike on New York City, following hard on US presidential acknowledgment that the Russians had succeeded in producing an atomic bomb.

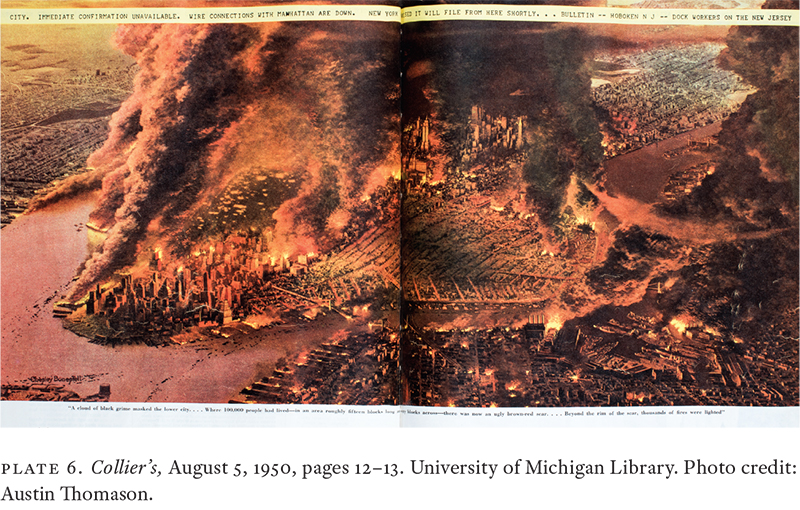

On the Collier’s cover, a full-color aerial image features a telltale mushroom cloud forming over a devastated lower Manhattan island, with the remains of the Battery and financial district in the foreground and the Empire State Building in the distance, its distinctive limestone panels aglow with reflections of the blast. Inside the journal readers were treated to a panoramic view of the devastation splashed across a full-color, double-page spread and overprinted with telegraphic confirmation of the strike. In this rendering, fires rage throughout lower Manhattan from the East River to the Hudson and beyond. Both the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge have collapsed and sunk to the bottom of the East River. Black carbon, produced from the instantaneous incineration of tons of infrastructure, has already entered the atmosphere and darkened the sky; the pall of its livid smoke engulfs the city as far as the eye can see.

The accompanying feature article by the Collier’s associate editor, journalist John Lear, supplements the dramatic visual perspectives from above with ground-level observation that brings the shock and horror of the impact and its home, onto familiar representational territory. Lear’s atmospheric opening reads this way:

The hands of the clock on the south wall of Cooper Union stood out sharp and black against the worn red stone. Thirteen minutes after five. The time was visible for blocks down the Bowery, where . . . broad hot shafts of midsummer sun were driving through the lower windows of the west, making the sidewalks shimmer and stink beneath their burden of the misadventures of Monday night’s derelicts.

The Collier’s animation of the documentary register is evident in the echo of John Hersey’s bombshell account of the bombing of Hiroshima, published four years earlier, which begins by telling the time of catastrophe. Beyond that, what better way to press the documentary character of the Collier’s enterprise than to train a documenting gaze on those familiar figures of Lower East Side lore, Bowery bums—“unhappy creatures” who “drifted” along the pavement, “listlessly exchanging powerful gusts of rum and gin, each too deeply involved in the mechanics of his personal navigation to concern himself with any of the others”?

Denizens of the Bowery had been staple objects of realist narrative and urban reportage for more than a century. They remained, in the postwar era, a default point of departure, a resource for coding the documentary enterprise as such. Ultimately, however, pressing the effects of nuclear devastation in America requires that the reporter focus on a more estimable figure. Sustaining a ground-level view, Lear’s narrative abandons the derelicts to trail “a tall distinguished graybeard” exiting a quick-lunch counter on Houston Street, close to the epicenter of the strike. Here, we presume, is a human loss that can count and be counted. Weeks later, “when they reached the spot” and “cleared away the wreckage of the El’s steel frame and the rubble” of the immigrant, working-class city—“the Uncle Sam House, the barber school, the headquarters of the National Chinese Seamen Union, and the shop which advertised BLACK EYES MADE NATURAL—15c”—the only index to the devastation is a “shadow burned into the cracked and chipped concrete,” the “radiant heat etching” of the graybeard “in the act of wiping his brow.”

Lear goes on to detail the aftershocks, fireballs, ash clouds, and panics that spread across the city, seaboard, region, and nation—all the implications of the horrific “fact” that “An A-bomb fell on the lower East Side of Manhattan Island at 5:13 P.M. (edt) today.” The journalistic and media point of Lear’s hypothetical documentary accounting—down to convincing statistics and vivid descriptions of death, trauma, and damage to civic infrastructure—is to awaken a post-Hiroshima American public to the fact that, in a climate of intense anxiety about Soviet military power, “we are pathetically unprepared to face . . . any A-bomb threat.” An editorial titled “The Story of the Story” details a Collier’s investigative method for producing this awakening. Lear’s preparation included extensive research and interviews with the staffs of the Atomic Energy Commission, War Department, and Defense Department and other nuclear physicists and engineers. He and his research team calculated likely death and injury by correlating census figures on population in New York City with AEC data on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (invoked without irony or comment). Their modeling, the editor confidently assures us, is meticulous, and “Every place and name used is real.”

“The Lower East Side looks backwards and ahead. It materializes a blighted past and a promissory note on American futurity.”

The one structural fact of the enterprise that goes unremarked—that appears, in other words, to need no explanation—is the siting of the fictive strike. To be sure, New York remained, in 1950, the most populous and densest city in the United States, with 7,891,957 total inhabitants in its five boroughs and 25,046 residents per square mile. And it was, Lear noted, “our greatest port, our most vital assembly and dispersal point for troops” in the context of the recent world war. For all these reasons, Manhattan would have been readily imaginable as the default target at the outset of the Cold War for a preemptive bid for world dominance.

But why, we might ask, the particular spatial logic of the strike and of Lear’s ground-level account? Why choose as a point of narrative origin Cooper Union, that iconic site of radical political discourse, of African American, immigrant, and labor activism, whose Great Hall was the venue for Abraham Lincoln’s decisive 1860 “right makes might” address opposing the extension of slavery, of Frederick Douglass’s post-emancipation rallying cry to African American troops, of important addresses against Indian removal during the 1870s by Native American leaders like Red Cloud and Little Raven, of key speeches for women’s suffrage by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, of the Yiddish-language address by shirtwaistmaker Clara Lemlich that kicked off an epochal garment workers’ strike in 1909, the same year in which the first public meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was held on that site? Why too the Bowery, the union hall, the tattoo parlor, the Third Avenue El, the downtown lunch counter, the view from across the East River? Why the Lower East Side as the go-to “trouble zone”—a self-evident site for imagining and envisioning the “eventuality” of world-historical, epoch-defining disaster?

Tactical thinking alone would not make this siting self-evident. If, as Lear notes, “a half million people live below 28th Street,” making lower Manhattan a diabolically attractive target, other parts of the city in 1950 had equal and even higher density rates. Ultimately, the choice of the Lower East Side seems predicated on the midcentury image repertoire of the ghetto and tenement district as a Möbius-like space: on the one hand, a historical zone of threat, danger, and everything potentially inassimilable to the American way of life (including Communists, radicals, Jews, and foreigners—figures of once and future menace); on the other, a crucible for metropolitan Americans—model minorities and alrightniks, imagined by Lear as urban citizens who “loved New York” and have thrived under the sway of “its magic spell.” It is precisely these twinned social and temporal effects that make the Lower East Side the default choice as ground zero in this Collier’s scenario, available both to conjure and to mediate Cold War angst. Janus-faced, the Lower East Side looks backwards and ahead. It materializes a blighted past and a promissory note on American futurity; it signifies both inhuman impoverishment and affirmative community, available to be harnessed to the postwar project of liberal democracy. Other spaces in the postwar city boast denser infrastructure, vastly greater capitalization, far more prominent institutions for commerce, culture, military activity, and art. But none is so available to mediate—to make experientially real, for readers—the challenges that face Cold War America, a democracy that is “not a good risk until it prepare[s] itself to survive.”

The value of the Lower East Side as a resource for the Collier’s thought experiment in mediation becomes clearer when we consider Lear’s “documentary” text in more detail. The initial apprehension of the attack, registered by an observer at a safe distance uptown, is “a babel of confusion” beneath “Great waves of purple and pinkish brown billo[wing] across the city,” “the powdered ruins of thousands of brownstone tenements.” In the near aftermath of the attack, aerial reconnaissance offers little more clarity. A “cloud of black grime . . . masked the lower city,” whose streets “could not be seen plainly”:

Many were blotted out entirely. In an area roughly 15 blocks long and 20 blocks across—from Canal Street north to Tenth and from Avenue B to Sullivan Street—where 100,000 people had lived—there was now an ugly brown-red scar. A monstrous scab defiling the earth. Somewhere in it, New York police headquarters, Wanamaker’s store, the pushcart market of Orchard Street, historic St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie and the famous arch of Washington Square were flattened beyond recognition.

All that remains of Manhattan between 38th Street and Battery Park is a vast tract of rubble, debris, and ash—“an agonized welter of suffering” and ruin, topped by the ominous fireball and mushroom cloud that are turning the sky over the Lower East Side “into a vast upsucking chimney.” Long after the moment of impact, devastation radiates outward from the epicenter and intensifies. Tens of thousands of homeless men, women, and children are left adrift, “roam[ing] the streets above Times Square.” Vermin and rodents, “attracted by the stench of decomposition within the bomb blast scar,” create epidemic conditions across southern Manhattan, which only worsen when inhabitants who had at first fled their ruined homes begin to return.

In the context of histories of documentary observation, such accounting seems neither futuristic nor prescient but distinctly familiar. It is, in fact, the return of a history that has never been repressed. Ruins and rodents, scars on the urban landscape, unimaginable suffering and uncountable hordes, illegibility and defilement: these have been the terms of art—the iconographemes—for representing downtown New York’s immigrant, working-class tenement district and its inhabitants since the earlier 19th century. “Here,” a firsthand observer writes of the area in 1850, “where these streets diverge in dark and endless paths . . . —here is the very type and physical semblance, in fact, of hell”; here, in the 1880s, “it is almost beyond the power of words to describe the fearfully congested condition” of the streets and dwellings, which are “a scene the full horror of which can only be appreciated by one who has gazed on it.” Here, in the closing decade of the 19th century, unspeakable tenement interiors disclose “shuddering showers of crawling bugs” that scatter only to reveal “the blacker filth beneath,” and the desperate immigrant who undercuts others’ wages with his underpaid labor “lives like the ‘rat’ he is.” In these real and iconic precincts comes to rest the detritus “rifled from the dumps and ash barrels of the city”; here, in places of cheap entertainment and on the streets are displayed persons and objects writer Luc Sante has described as “too shoddy, too risqué, too vile, too sad, too marginal, too disgusting, too pointless” to find a home elsewhere.

It therefore comes as no surprise that Lear’s account would reanimate a historical image repertoire of the primitive, atavistic, wasted Lower East Side as a terrifying, postatomic, dystopian future. In the Collier’s “reportage,” the midcentury project of urban renewal for which the historical tenement district was a key target reappears as a fantasy of demolition gone amok. The once teeming ghetto is now atomically uncontainable, its iconic tenements pulverized to contaminated waste in the form of “ashes” and “cloud” that blanket the entire city. Likewise, the historical “babel” of the immigrant streets recurs as a condition of unfitness to which the city’s traumatized residents regress. The entire population of lower Manhattan is reduced to the state of dazed and homeless paupers, the kind of “helpless human wrecks,” in Jacob Riis’s words, who figured so prominently in 19th-century exposes, sensational journalism, reform tracts, and naturalist fiction of the ghetto. The ravaged Lower East Side of the other half has rematerialized as an “upsucking chimney,” threatening, in Lear’s imaged future and in the Collier’s “documentary” imaging, to draw the entire city and all its landmarks of cultural achievement, economic might, and power into its vortex.

__________________________________

From How the Other Half Looks. Used with permission of Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Sara Blair.