New and Noteworthy Nonfiction You Should Read This December

Johnny Cash, Siri Hustvedt, Rachel Carson, and More

Michael Stewart Foley, Citizen Cash

(Basic Books)

Like Bruce Springsteen, Johnny Cash has long been one of those iconic American artists widely claimed by both the political left and right: he’s proud to be American, but wholeheartedly on the side of the underdog; though defiant, profane, and archetypically masculine, he’s got the soul of poet; he’s tough, but wounded. But what, exactly, were the politics that informed songs like “Folsom Prison Blues,” “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” “There Ain’t No Good Chain Gang,” and many more? Such is the project of Michel Stewart Foley’s Citizen Cash, to dig a little deeper into what some have seen as Cash’s political contradictions, but which Foley—through extensive access to hitherto untapped archives—reveals as an artist’s fundamental commitment to empathy, in both his work and his life. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor in Chief

Siri Hustvedt, Mother, Fathers, Others

(Simon & Schuster)

I’ve said it before, but Siri Hustvedt is one of our great living essayists. Covering a staggering range of subjects, with an erudition and incision leavened by deep reserves of humanity, Hustedt again and again poses urgent questions about who We (capital W) are, and how we’ve gotten here (the edgelands of a civilization suspicious of its own decline). In Mothers, Fathers, Others, Hustvedt moves through memories of the women in her own family to investigate what role the maternal has in a patriarchal society, expanding outward into considerations of great artists like Jane Austen, Emily Brontë, and Louise Bourgeois. Everyone should read Hustvedt. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor in Chief

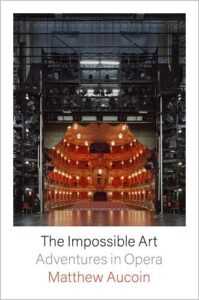

Matthew Aucoin, The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

These days, it seems, Matthew Aucoin’s work is everywhere: he received a MacArthur fellowship in 2018; The New York Times Magazine has called him “the most promising operatic talent in a generation”; just last month, Eurydice, his operatic adaptation of the ancient myth (including a libretto by Sarah Ruhl), opened at the Metropolitan Opera. The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera reflects on the history of the form, its reputation and reality as one of the most difficult to pursue (on the part of composers and performers alike), and the works that have built the canon from its earliest days in Florence to the experimental work that is challenging traditional approaches today. The book also incorporates his own extensive experience working in opera, in particular the creation of Eurydice, giving a rare behind-the-scenes look at an art form with a reputation of being particularly impenetrable to outsiders. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Rachel Carson, The Sea Trilogy

(Library of America)

Rachel Carson set the gold standard for socially conscious environmental writing with her landmark book Silent Springin 1962. Before that, she authored three other books—Under the Sea Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), and The Edge of the Sea (1955)—on ocean ecology, conservation, and marine life, works that drew on her experience as a biologist for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. Now, Library of America is re-issuing all three of these in a single hardcover; it’s an astounding body of work from arguably the most important early environmental writer in America. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Charlie Warzel and Anne Helen Petersen, Out of Office: The Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working from Home

(Knopf)

The pandemic has exposed many of the failures of our current capitalistic, patriarchal white supremacist society, including our relationship to work. During the height of the pandemic, many people were allowed the privilege of working from home. But who does it really benefit? Well, according to Charlie Warzel and Anne Helen Petersen, remote work contains a “dark truth.” Remote work may look like an opportunity to fully redistribute power back to employees but as the authors argue, “in practice it capitalizes on the total collapse of the work-life balance.”

However, make no mistake, Out of Office is not an absolute dismissal of remote work. Rather, similar to the wisdom echoed in Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing, they ask us to reconsider our emotional devotion to labor and reprioritize the things that matter most. Throughout the book, Peterson and Warzel thoroughly examine the evolution of four important concepts: flexibility, culture, technology, and community. In “Flexibility,” they explore how companies have abused this idea for their own benefit. “Culture” looks at corporate culture, namely the disparities between the stated corporate culture and how that culture is played out in everyday workplace interactions. “Technologies of the Office” focuses on how technological advancements have contributed to toxic productivity culture, and “Community” unpacks the historical rise of individualism and the benefits of collectivism. At the end of the book, there is useful advice to bosses, particularly how they can help change the future of labor for the better. Out Of Office is not an easy cure-all for the various problems and inequities that plague our current workforce, it’s a call to action: we only get one life, so why should we believe that we must live to work? –Vanessa Willoughby, Lit Hub Assistant Editor

Joe Moshenska, Making Darkness Light: A Life of John Milton

(Basic Books)

In his introduction to Making Darkness Light: A Life of John Milton, Joe Moshenska is careful to note that the book will not strictly follow the rules of a traditional biography. He writes:

Milton fascinates me in part because his writings display to an unusually intense degree the desire shared by many, perhaps all, writers of literature: to intertwine his words and thoughts with the words, thoughts, and lives of his readers; to change them.

Of course, anyone looking for a deeper understanding of the facts of Milton’s life and the context for his poetry will certainly find what they’re looking for here. Making Darkness Light includes not only moments in Milton’s life and the landscape of 17th century England as well as close readings of his work. But it’s the exploration of what the author describes as one of Milton’s deepest occupations, “the place of literature in a life,” is what sets the book apart. Moshenka has no aspirations to separate the biographer from the biography, and Making Darkness Light is richer for his presence throughout the book. –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Ellen Screker, The Lost Promise

(University of Chicago Press)

Ellen Schreker’s The Lost Promise is an exploration of American universities during what she refers to as the “Long 60s”—a period in which academia was believed to be a site not only of upward mobility, but also through which critical challenges to racial and gender inequalities could be raised and addressed. Schreker considers the centrality of universities in American life, and the ways in which that centrality eventually crumbled. Tracking both the “growth” and “turbulence” of schools, she writes:

in the 60s, colleges and universities expanded so exponentially that their traditional folkways simply imploded. Many institutions would have been disrupted even if the rest of the United States had been calm. But it was not. Despite—or perhaps because of—the country’s relative affluence, the struggle to fulfill the democratic promise of higher education in the face of racism, sexism, and US warmongering ensured turbulence.

Indeed, the veil eventually dropped. And it is the very complexities of this drop—the many forces and terrains therein—that are at the heart of Schreker’s book. As she rightly reminds us, there is “no single story.” Her project instead follows the threads that make up the lost promises of higher education. –Snigdha Koirala, Lit Hub Editorial Fellow