Nell Irvin Painter on Writing About Anything (and Everything)

A Call to Authors and Publishers Alike

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Who can we write about?

What a dumb question! The answer is obvious. You or I can write about anything we want to write about, as myriad authors have shown over the eons. From its earliest beginning in about 4000 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia, writing was primarily for business purposes: recording expenses, debts, inventories, and contracts. Millennia later in the United States, authors from the obscure to the fabulous have written an astounding array of texts. Closer to our own times, 19th-century Black authors self published at least 578 texts, according to a list on the website of the American Antiquarian Society. Those authors could write what they wanted to say. Getting their word out was another matter, because writing and business are still intertwined.

So why am I asking such a dumb question? Because in 2020, easily within living memory, a white woman, Jeanine Cummins, published American Dirt about a Mexican migrant family, and protests flew targeting the author’s identity and claiming cultural appropriation. The question was whether a white author, even this particular white woman author, could write about people whose identity she didn’t share. Well of course she could. And she did, earning a seven-figure advance, receiving Oprah’s imprimatur, and staying on the bestseller list for 36 weeks. This white woman not only could write about whatever she wanted; she made bank in the process.

I say the question really wasn’t, isn’t, about the author’s identity and her ability to write. In today’s and yesterday’s book world, it’s not so much the writing that’s in question. It’s about the infrastructure of publication and distribution: the mechanisms of getting your words out into the world. It’s about the business. It’s about whether your publisher is stable enough to last long enough to get your words into print. (Harriet Jacobs’s original publisher went broke before bringing out Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.) It’s about the 21st-century competition between publishers wealthy enough to pay an author a seven-figure advance (for American Dirt), to wage a broad and deep publicity campaign, to send hundreds of free books to prominent and powerful people, to know book reviewers who will let the world know the book exists. It’s about the infrastructure that over the centuries lay beyond the reach of hundreds of authors I’m calling “us,” the infrastructure that in the 19th century failed Harriet Jacobs and in the 20th century shortchanged Paule Marshall, Leon Forrest, Arna Bontemps, and Marita Golden during their lifetimes.

I’m tempted to conclude that literary convention limits Black authors to a limited range of subject matter. Yes, there’s infinite variety within the realms of Blackness. Yet still, Black people only.

The publishing business is the part that has stymied us over the decades. “Us” being Black authors, women authors, authors of color, communist authors, authors without formal education in the 20th and early 21st centuries. The more pertinent question than what we can write is what we who are Black authors can write about that a publisher will publish, will publicize, will market and distribute widely. It’s easy and very mostly right to see the whiteness of publishing as the culprit in the business, a fatally limiting culprit in the past.

Nowadays Black women, for instance, can write and publish original books, reach huge audiences, be widely and positively reviewed, win prizes and honors galore, and rightly so. I’m thinking of stunningly written and stunningly successful works of nonfiction like Imani Perry’s Looking for Lorraine and South to America, and fiction like Honorée Fanon Jeffers’s The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois. These are authors and books for whom the publishing business worked well, though I doubt seven-figure advances came into play. No question but that today’s Black authors no longer fall victim to the kind of 20th-century neglect that condemned Zora Neale Hurston to an obscure, impoverished old age.

But that’s not the question I started with. I asked: who can I and we write about when I and we are Black authors? Those accomplished authors I mentioned wrote about Black people, and Black people and race in America are the subjects of virtually every book by a Black author of fiction, of nonfiction, and of journalism. I’m tempted to conclude that literary convention limits Black authors to a limited range of subject matter. Yes, there’s infinite variety within the realms of Blackness. Yet still, Black people only.

But wait! you say, knowingly pointing to a bestselling Black author of the 20th century, Frank Yerby, with his string of Book of the Month Club historical novels and romances. Yerby published countless poems and novels that sold some 25 million copies. But his success rested on books whose covers depicted white characters, so many of his readers likely didn’t realize he was Black.

My own early 21st-century bestseller, The History of White People, carries an unmistakably Black author’s photo, and its title, reinforced by its cover, indicate its subject matter: white people. Yes, a positively and widely reviewed bestseller. Doesn’t this book prove that I—we—can publish on anything and anybody? Why was this so exceptional? Did it feel like a trick? Did buyers still see it as a book about Blackness? You would have thought so hearing the questions from audiences at my book events.

Which brings me back to the publishing business rather than solely to the author’s identity. If publishers are willing to invest—another business term—we authors can write about anything. Consider this a call to authors and publishers to look less to identity and more to marketing to let us read what Black authors have to say about everything and everybody.

____________________________________________

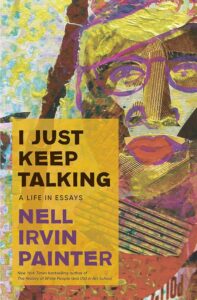

I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays by Nell Irvin Painter is available now via Doubleday.

Nell Irvin Painter

Nell Irvin Painter, Edwards Professor of American History, Emerita, Princeton University, is the author of books of history including the New York Times bestseller The History of White People; Sojourner Truth, A Life, A Symbol; the National Book Critics Circle finalist Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over; and the forthcoming I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays. A Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences since 2007, she has received honorary degrees from Yale, Wesleyan, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dartmouth. Nell Painter lives and works in East Orange, New Jersey, and has made artists’ books in residencies such as MacDowell, Yaddo, Ucross, and Bogliasco. She currently serves as Madame Chairman of MacDowell.